Many of us today are thrust into the role of lay death midwife unwittingly. There are altruistic hospice volunteers and angelic professional death doulas and hospice chaplains and hospice nurses who feel called to work with the dying. They choose the difficult and rewarding task of supporting people transitioning out of this life. To care for a dying stranger can be distressing — even for those who see death regularly — and it can be profound. It’s an entirely different experience to sit vigil by the bedside of someone who recently sat across the kitchen table from you, your heart breaking as a partner or a parent or a child or a friend becomes a ‘dying person.’ Either way, it’s sacred work. Because I believe in the empowering potential of archetypal thinking, I thought I would offer up a look at Hermes, the Greek god of transitions and boundaries, for the death midwives among us, whether we are professionals or grieving loved ones (or both).

Coin-less souls were forbidden crossing, and doomed to wander or wait one hundred years for a free ride.

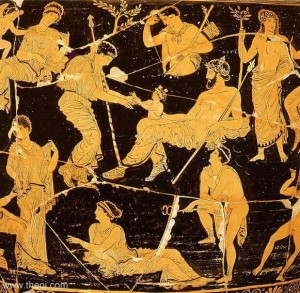

Hermes is one of the best known of the mythological psychopomps, or spirit guides. The purpose of the psychopomp (from the Greek word psuchopompos, meaning conductor of souls), is to escort souls through transitions, primarily the transition of the newly departed soul into the afterlife. Throughout human history, shamans and others with the ability to travel between the spirit and material worlds have served this function. Sometimes dead ancestors and friends or mythological figures act as companions. Hermes, known as Mercury in Roman mythology, moved freely between the worlds of the mortal and divine, and served as a messenger of the gods.

He was also characterized as trickster, magician and as god of communication and commerce, but the most mystical was his guise as god of liminality (the in-between space, space of transition, threshold) and escort of the recently dead. It was Hermes’ job to lead the soul safely to the shores of the mythological River Styx, the boundary between the earth and the Underworld, where he handed them off to Charon, the ferryman. Passage across the River Styx cost one coin. It was customary to place a coin in the mouth of a dead person, ostensibly to make sure they could pay Charon for his services. Coin-less souls were forbidden crossing, and doomed to wander or wait one hundred years for a free ride.

And death can feel a lot like violent abduction, especially when it’s by tragic accident or is preceded by terrible suffering.

In another seminal story from the Greek mythological cannon, the goddess Persephone is kidnapped by Hades, god of the Underworld, and sequestered in his realm. With Hades as chaperone, death is violent abduction. And death can feel a lot like violent abduction, especially when it’s by tragic accident or is preceded by terrible suffering. The myth of Hermes provides the option to interpret death as transition rather than abduction. Shepherded by Hermes, death becomes a benevolent descent. Sitting vigil with the dying gives us to the opportunity to act as Hermes-esque death doulas to transitioning souls — to frame death as a rite of departure from this inherently liminal world.

Hermes the Death Doula

Hermes the Death Doula

Meaning-Focused Grief Therapy: Imaginal Dialogues with the Deceased

Meaning-Focused Grief Therapy: Imaginal Dialogues with the Deceased

Flawed Kidney Function Test Discriminated Against Black Patients

Flawed Kidney Function Test Discriminated Against Black Patients