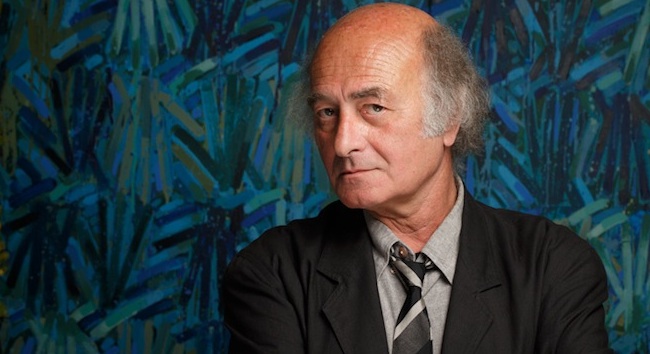

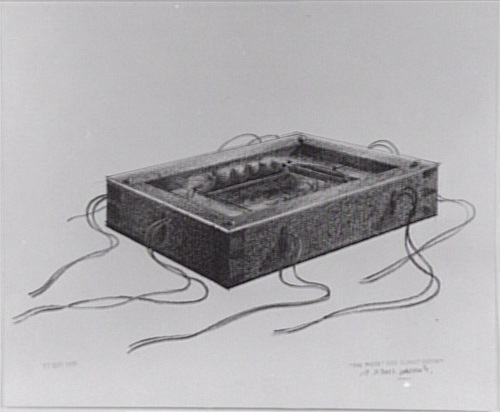

It took Gérard Titus-Carmel (1942-present) over a year to finish his work, The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin. Completed in July of 1976, Coffin is made up of 127 drawings (and one physical model) of various sizes and techniques of the same object. The collection offers a perceptive commentary on many themes common in the French artist’s work: the natural and artificial, the authentic versus the fantastic, regeneration, destruction and death. Through an act of calculated redundancy, Titus-Carmel’s exhaustive study of the box brings us to reflect upon our relationship with death and dying.

It takes much more than a glance at one of the drawings to know what one is looking at. There is, after all, no real sense of the object’s scale. Is it a battery? A coffin? Some kind of bizarre iPod? Its rectangular shape incites utility, but an air of mysticism — even fascination — pervades this object that has been so fanatically drawn and re-drawn.

“It takes much more than a glance at one of the drawings to know what one is looking at. There is, after all, no real sense of the object’s scale. Is it a battery? A coffin? Some kind of bizarre iPod?”

“The little mahogany box,” explains the artist, “is a dozen or so centimeters long. It’s closed by a little plate of transparent altuglass. The bottom is covered with a mirror. Inside is a wicker oval, partially wrapped up in synthetic fur…the oval is held together by six cords that hang from the box’s sides.” Even through this description, one can see the elements of ritual applied to the box. It almost feels like a talisman of sorts. Initially, the artist had the idea to create the series after reflecting upon a box of matches in his pocket: “In my pocket, the box of matches, the minute coffin, imposed its presence more and more and obsessed me… It was not necessary that the coffin, of reduced dimensions, be real. On this small object the coffin for solemn funerals had imposed its power.”

Thus, the creation of the “Tlingit pocket coffin,” a tiny rectangle with a Native American name, was born. But its creation inspired an opposing result: reflections on death. Titus-Carmel’s 127 drawings are reflections on the proximity of that inescapable end, of our physical relationship to dying. He drew his “coffin” from every perspective, examining “death” from every angle in the possible chance that its mystery might become tangible, clear. However, as Titus-Carmel found, each drawing brought a new perspective. Death was not a single, frightening subject to decode, but something of unending variation.

“Death was not a single, frightening subject to decode, but something of unending variation.”

Today, the artist’s 127 drawings can be found in Paris’s Pompidou Museum. But they hang as a kind of creative byproduct — a souvenir of a process that ended up containing more significance, more beauty in its reflections, than its final creations. “The pencil roams,” explains Titus-Carmel on the process, “accentuating its grooves, and this groove becomes the trace of a certain mental state.” In that moment, death opens a doorway for self-exploration.

Mortality in Your Hands: “The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin” by Gérard Titus-Carmel

Mortality in Your Hands: “The Pocket Size Tlingit Coffin” by Gérard Titus-Carmel

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival