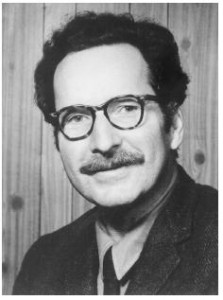

During our childhood, gradually through observation then perhaps all at once through our parents’ telling, we all come to learn that our life will not last forever. We become aware of death. Oftentimes, when we face death in our adult lives, we think about it again. We fear it, and it makes us think about our life. How to define it. What we want to accomplish, how much time we might actually have, how many years ahead, how much is left undone. We can’t think about this forever. Consciously or not, we are forced to file away any final decisions on the subject somewhere else in the back of our mind. It’s just too scary for us to deal with in all totality. We wouldn’t be able to function for fear of all the dangers around us. According to a major school of psychology, for which the famed Dr. Ernest Becker was and is its most eminent figure, we spend much of our lives grappling with this struggle — the result is, well, life.

During our childhood, gradually through observation then perhaps all at once through our parents’ telling, we all come to learn that our life will not last forever. We become aware of death. Oftentimes, when we face death in our adult lives, we think about it again. We fear it, and it makes us think about our life. How to define it. What we want to accomplish, how much time we might actually have, how many years ahead, how much is left undone. We can’t think about this forever. Consciously or not, we are forced to file away any final decisions on the subject somewhere else in the back of our mind. It’s just too scary for us to deal with in all totality. We wouldn’t be able to function for fear of all the dangers around us. According to a major school of psychology, for which the famed Dr. Ernest Becker was and is its most eminent figure, we spend much of our lives grappling with this struggle — the result is, well, life.

Psychology emerged as a major school of study in the early 1900’s, roughly around the same time that Kierkegaard and the existentialists were grappling with the meaning of human society — progress or lack thereof, the future and what it holds for us. With religion playing an increasingly less prominent role in day to day life, with the advent of the world wars, vast new scientific frontiers and the apparent irrationality of modern times, the world was beginning to ask itself, “Where is this all going?” Sigmund Freud was one of the first scientists to look inward for the answers, into the human sub-conscious, the id, the ego, and his famous Oedipal Complex. Freud’s basic thesis was that the sex drive, the urge to reproduce, was the definitive drive in human nature. Freud is largely credited for popularizing psychology, and he remains one of the towering figures in 20th Century thought. But, like anyone else, he has many detractors. Legions of psychologists and scientists and university courses since have sought to refine and correct and poke holes in the man’s theories. One such, hugely successful, was Ernest Becker. According to Becker, and as put forth in his seminal work, The Denial of Death (1973), while Freud got the theme right, he got the motivation wrong. Human beings are driven by sub-conscious urges, yes, but it’s not the sex drive, primarily. It’s the death drive, or, more accurately, the all-consuming fear of death, that great unknown and constant threat of terminus to all things known. We poor humans, when it comes down to it, live and die much like all other earthly animals do. We are born, we age, we eat, we love and, eventually, we die. But, unlike other animals, we are self-aware in the meantime. We are cursed with the ability to wish that it were otherwise. We are aware of the constant threats all around us, of our fragility and our tiny little place in this huge and scary cosmos. We spend much of the rest of our lives attempting to define ourselves against this reality, and it is this very drive that leads us to do pretty much everything that we do. Becker calls it our drive to ‘heroics’ — to build a family, to create art, to find success within society, to leave a legacy larger than we were. In essence, to live a human life as our culture knows it.

As Becker pursues this line of reasoning, what he ultimately gives us is something as close to a written attempt to grapple with the very meaning of life as any author every could have gotten. We are in combat with death every day. It is a fight that none of us can win, but that isn’t for lack of trying. Our urge to grandeur and self-worth makes us who we are. This urge can be as destructive as it can be positive. Indeed, much of Denial of Death is a sobering read indeed. But there is always humanity at the end of it, we and our fellows’ attempts to see more than we can and be more than we are.

Isn’t it interesting, how a book about the psychological effect of death, becomes a book about the inner mechanics of life.

- Learn more about our relationship to the dying process in our review of Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’ influential “On Death and Dying”

- Read about Judaic memorial and celebratory practices through our post on Jewish candle-lighting ceremonies

- Discover how art can help parents and children through the grieving process

“The Denial of Death,” by Ernest Becker

“The Denial of Death,” by Ernest Becker

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”