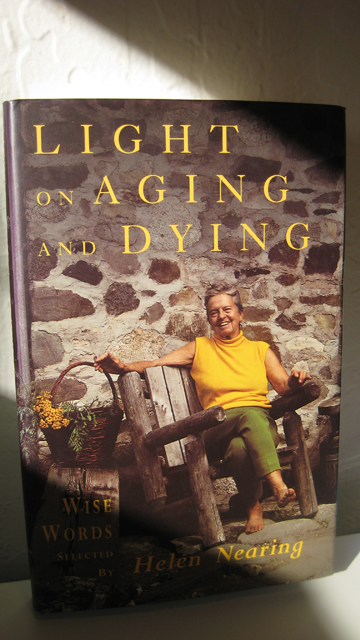

Helen Nearing on Her Farm

I was recently rummaging through an old bookstore when I stumbled on a copy of the book Light on Aging and Dying, by Helen Nearing, written when she was a widow. I was familiar with Helen and her husband Scott’s seminal book, The Good Life: Helen and Scott Nearing’s Sixty Years of Self-Sufficient Living, having read it years ago. Written in 1954, the book helped launch the back-to-the-land movement as part of the 1970s counterculture. Its ideological footprint remains with us today as evidenced even by my local grocery here in Potrero Hill, named The Good Life, which began as a co-op back in the 70’s. More than a “how-to” book, The Good Life is woven with the politics of the Nearing’s beliefs on non-exploitation and how they implemented their ideas of social justice into their lifestyle.

Light on Aging and Dying is a collection of sayings Helen Nearing assembled in the spirit of her life following her husband’s death. The Nearing’s were New York City intellectuals who in 1932, during the worst of the Great Depression, walked away from city life to buy an old run-down farm in Vermont. With their own hands, they built their house, garden and diet around their (at the time) radical beliefs. The impetus for their life change had more to do with Scott, an economics professor, having been terminated for his “Socialist Pacifist” beliefs. They made a living by producing maple syrup as part of a local community effort they coordinated, and when it fell apart they moved to Maine and started all over again. They both wrote a number of books along their life journey and when Scott was just 18 days past his100th birthday, he died. He appropriately chose to end his failing life by abstaining from food, intentionally avoiding doctors, hospitals, pills or force-feeding. At the very end Scott was a pioneer of self-empowerment because of his beliefs.

Following Scott’s death, Helen Nearing, as a widow, had much time to think and reflect on aging and death – and as the title of her book shows, she approaches it lightly. She assembled a wonderfully diverse collection of sayings on the subject reaching back to the Egyptians and forward to the modern day, all hinged on the inspiration of their life off the land. She begins the book with a foreword that is both uplifting and positive to set the tone; here’s my favorite passage:

“When I was nearly ninety, among the countless visitors who came to our Forest Farm was a little girl with her parents. She listened to the appreciative comments on my great old age and watched me as I moved easily around the house and garden. Before they left, she handed me a paper on which she had made a crayon drawing ‘To Helen,’ with pine trees in the foreground, two little flying birds, some notes of music they were singing, and the words: ’89 ISN’T SO BAD.’ It is possible she may remember that when she becomes my age.”

Joan Didion in her Home

This past week as part of the City Arts & Lectures series (our local NPR) at Herbst Theatre, I heard the widow Joan Didion speak. Her thoughts made me consider the notion of how widows reflect on aging and dying. She just released her new book, Blue Nights, an account of the death of her daughter Quintana Roo, who died a few years after Didion’s husband. In answering questions regarding losing Quintana, it became apparent that Didion was uninterested; she has investigated death with two books now and has since moved on with her life. Instead she reflected heavily on accepting the present and future, noting, “No one will ever know me as 23 again.” She summed up the end of a long monologue with the sweet acceptance of an aging widow.

Both Nearing and Didion have enjoyed long, active, and fulfilling lives. As widows they’ve both had the luxury of experiencing aging and living to share it. And just like its cover, Nearing’s book invites you to sit and lounge in a hand-hewn chair in the sun and reflect on days past, as well as ponder what it’s like to be 90 years old in Nearing’s enlightened day and age. I end with her last selected saying, appropriately by Maurice Maeterlinck, known for his writings on death and the meaning of life:

“Many things, beyond a doubt, remain to be said which others will say with greater force and brilliance. But we need have no hope that one will utter on this earth the word that shall put an end to our uncertainties. It is very probable, on the contrary, that no one in this world, nor perhaps in the next, will discover the great secret of the universe. Behold us then before the mystery of the cosmic consciousness.”

Widows Reflect on Aging and Dying

Widows Reflect on Aging and Dying

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville