Memento mori is a Latin phrase that literally means, “remember to die.” As an art form, it has encompassed but is not exclusive to memorial art, and serves to this day as a reminder to live life fully and mindfully. Memento mori art has taken on many forms, from painting to sculpture to jewelry, often depicting a human skull or human remains.

The memento mori started appearing in Europe around the Middle Ages, in response to the Black Death (or, as it was called at the time, ‘The Great Pestilence” or ‘The Plague’), which wiped out 20-60% of Europe’s population over the span of approximately 150 years. The Black Death was resistant to all known remedies at the time, including everything from bloodletting to prayer. This situation, as you might have guessed already, sparked a lot of thought about what it means to live and die well.

“Vanitas Still Life” by Jacques de Gheyn the Elder (1603)

(Credit: experimentaltheology.blogspot.ca/)

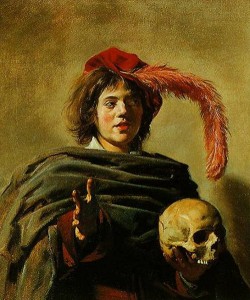

Several distinct themes or genres can be found within the scope of the memento mori, including vanitas (vanity) and Danse Macabre (Dance of Death). Vanitas works depict the reality that physical beauty is temporal and therefore illusory – in other words, not grounded in truth that survives throughout the ages. These works encourage the viewer to cultivate that within them that has ageless resonance, and not self-identify with, or be attached to those aspects of their physical reality that will fade. Vanitas symbols include — but are not exclusive to — the skull, smoke, bubble, flower and images of earthly wealth. All images represent the transiency of life.

Danse Macabre works depict death as personified by a skeletal human form, often in the role of jester or musician, with a variety of instruments in hand. Young and old, rich and poor alike are escorted to the grave with great joviality, reminding us that no one can escape this universal experience, and so should greet their dying time without aversion. Some of the Death figures seem gently concerned for their distressed wards.

“Rosario” (2008), an installation by artist Javier Pérez, including life-size bronze skulls

(Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

No matter what your beliefs are about the afterlife, your dying time will compel you to level up with how you’ve lived your life. According to Stephen Jenkinson, founder of the Orphan Wisdom School and author of Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanity and Soul, one of the primary wounds in North America’s approach to palliative care and, more widely, how we in the West approach death, is that dying people don’t spend their time trying to die, but rather trying to live, and so miss out on this time to reflect and attend to anything unresolved. The memento mori, in this sense, remains a powerful contemplative tool that we can all benefit from including in our lives.

Memento Mori: Remembering Your Own Death

Memento Mori: Remembering Your Own Death

Forest Bathing Eases Grief by Soaking in Nature

Forest Bathing Eases Grief by Soaking in Nature

The Spiritual Symbolism of Cardinals

The Spiritual Symbolism of Cardinals

Meaning-Focused Grief Therapy: Imaginal Dialogues with the Deceased

Meaning-Focused Grief Therapy: Imaginal Dialogues with the Deceased