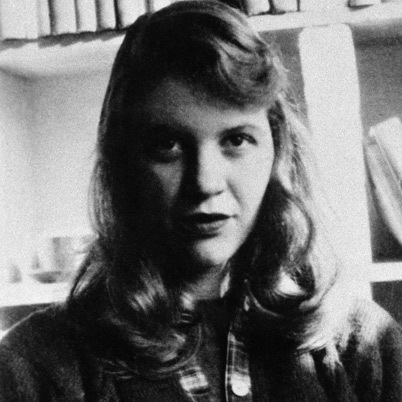

Mourning the loss of a father, regardless of the status of a child’s relationship to him, is never easy. One of my absolute favorite poets, Sylvia Plath, wrote a poem called “Daddy” in 1962 shortly before her suicide. Plath’s “Daddy” explores a daughter still undergoing the five stages of grief even though he died about 20 years ago when she was a child. Given Plath’s own childhood loss of her father, his pro-Nazi stance and the heavy German and Holocaust imagery, many scholars and critics have speculated that this poem is autobiographical. Plath herself, however, steered clear of confirming this speculation and instead introduced it at a BBC radio reading shortly before her death as a poem about “a girl with an Electra complex [whose] father died while she thought he was God. Her case is complicated by the fact that her father was also a Nazi and her mother very possibly part Jewish. In the daughter the two strains marry and paralyze each other – she has to act out the awful little allegory once over before she is free of it.”

The daughter’s idolization of her father—both when he lived and after he died—has stayed strong all these years as evidenced in the first stanza and a half.

“Daddy” commences with the narrator struggling with the denial stage of grieving over her father’s death no matter how many years it has been. The daughter’s idolization of her father—both when he lived and after he died—has stayed strong all these years as evidenced in the first stanza and a half. In order to survive, the narrators says, “You do not do, you do not do/Any more, black shoe/In which I have lived like a foot/For thirty years, poor and white,/Barely daring to breathe or Achoo./Daddy, I have had to kill you/You died before I had time—.”

The narrator’s grieving over the “bag full of God” or what she always thought her father to be quickly changes to her angry admission that “I have always been scared of you,” and subsequently accuses him of being “Not God but a swastika/So black no sky could squeak through./Every woman adores a Fascist,/The boot in the face, the brute/Brute heart of a brute like you.” Her childhood admiration of him compounded by her acquisition of realizations about his true nature results in the conflicting emotions leading to her angry outburst.

Many people who grieve over the loss of a loved one, specifically a father, can relate to the strong hope and desire to bring the dead back to life, and the crushing sadness when we know our loved one is no longer accessible.

The anger dissipates into a combination of bargaining and depression for the narrator. Many people who grieve over the loss of a loved one, specifically a father, can relate to the strong hope and desire to bring the dead back to life, and the crushing sadness when we know our loved one is no longer accessible. The narrator informs her dead father that “But no less a devil for that, no not/Any less the black man who/Bit my pretty red heart in two./I was ten when they buried you./At twenty I tried to die/And get back, back, back to you./I thought even the bones would do./But they pulled me out of the sack,/And they stuck me together with glue.” The narrator’s turmoil through the bargaining and depression stages mirror what people who grieve go through, specifically those more prone to severe depression and suicidal tendencies like Plath herself.

The narrator finally reaches the acceptance stage by deciding to “make a model” of her father that she can physically kill once and for all. She announces that she is done with grieving over his death by saying, “There’s a stake in your fat black heart/And the villagers never liked you./They are dancing and stamping on you./They always knew it was you./Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.” Even with her acceptance of her father’s death, she still holds on to some residual anger—more so because of how he treated people during the Holocaust—which in turn makes it easier to accept the finality of the situation. We all have our own ways of coping with loss for the remainders of our lives even after all five stages of grief are completed.

You may also enjoy:

“Daddy” by Sylvia Plath

“Daddy” by Sylvia Plath

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival

A very sad part of Sylvia’s life. Interesting take on her words directed towards her father.

Report this comment