Courtesy of Dr. Marianne Matzo

Dr. Marianne Matzo first became interested in working with the dying during her Ph.D. program, when she was exploring whether people were considering long-term care and how they would pay for it. A friend told her that she would commit suicide before entering long-term care. This statement inspired Matzo’s dissertation on the prevalence of nurse-assisted suicide, which led her to explore nursing education in end-of-life care.

Matzo, who now holds a Ph.D. in gerontology, worked as a nurse and nurse practitioner in oncology and palliative care for more than 40 years. She is currently the executive director of Everyone Dies, a nonprofit that produces educational podcasts about end of life. She also co-wrote a textbook on palliative care and recently published a children’s book about death. Matzo agreed to speak with SevenPonds about some simple ways to comfort a dying loved one.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarification.

Thanks for chatting with us, Marianne! In your opinion, what makes a good death?

Honestly, I don’t think my opinion matters. It’s like getting a nice big bowl of pasta and saying “This is delicious,” and somebody else saying, “This tastes really horrible.” It’s an individual taste. Some people want every bit of technology they can possibly have, because holding onto any second of life is really important. Other people are like, “If I can’t go to Target anymore, I’m ready to die.” So there’s this wide range. For me personally, I’d like to not know it was coming, which would mean quick and sudden. But I also know that in terms of complicated grieving that makes it very difficult for people left behind.

When a loved one is dying, what can friends and family do to provide comfort?

It would be ideal if people talked about it ahead of time, and had a sense of what you would like. Some people appreciate a great party, and all kinds of people coming and going, and lots of beer and popcorn, or whatever it is. And some people want to be just left alone. A big part of it is talking to people and saying, “What are your wishes?” I was with one family who brought a tape player with all Christmas music, because they knew their mom liked Christmas music, so she died to that Christmas music. Other people might want country. I think the perception is that you’re supposed to put on nice, quiet music, maybe somebody playing a harp, and it’s calm. But unless that’s how your family works, then that’s probably going to be pretty foreign and uncomfortable. People make playlists for their wedding or for other events in their lives, and I think it would be nice if people made a playlist for their death. What songs bring you joy? What songs bring you happy memories? Have those to play, because it’s your death, and it should be your music.

Matzo scuba diving in Cancun

Courtesy of Dr. Marianne Matzo

If you think about what’s brought the person comfort, you can do those things when they’re dying. For example, my mother’s feet always hurt her, and we had this one dog who loved to lick her feet. My mother liked that, and she liked a foot massage. So when she was under home hospice care after a major stroke, and I was taking care of her, when I bathed her every morning, I also soaked her feet in warm water, dried them off and massaged them with cream. My mother was also extremely deaf, and people who came to visit would talk to her very quietly. And I would say, “You know, she’s still deaf!” There’s all this mystery surrounding the end of life. But if they always enjoyed a foot rub, then that’s what you do. If they always hated their feet being touched, leave their feet alone. If they were deaf, they’re still deaf.

You can simply take a blanket or towel and put it in the dryer, get it nice and warm, and use it to dry them off after a bath, or cover them. We kind of die from the outside in. The body says, “I’m going to protect my heart and lungs and brain. And everything else – I don’t care if it gets any blood.” So people get really cold, and you can provide an outside source of heat like a warm blanket that’s not going to get too hot, that’s not going to burn them. You don’t want heating pads all over them, because they aren’t going to have the feeling to know they’re getting burned. You can also keep their mouths moist. A lot of times people at the end of life either become more slack in the jaw, so they’re mouth breathing, or they are on medications that make their throats dry. So they might not be able to swallow, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t take a swab or a wet washcloth and wipe around their lips, or just give them a little spritz of moisture to make them feel more comfortable.

Sometimes we forget about things like washing their face and hands with warm water. I wash my hands probably 50 times a day – I’m a nurse, and it’s just ingrained in me. So when I’m dying, if someone leaves my hands sticky, I’m not going to like it, and I don’t know if I’m going to be able to say, “Can I please have something to wash my hands with?” Hopefully somebody knows me well enough to say, “I’m going to wash your hands.” Or people with dry crusties in their eyes – don’t leave them there. Place a warm cloth over their face, let them pretend it’s spa day.

Another thing you can do is maintain a person’s style and presentation. When I was taking care of my mom, it was a few weeks before Christmas, and I went in the back of her closet where she kept her Christmas sweaters. I could hear her in my head, saying “Don’t you dare cut up my Christmas sweatshirt,” and I thought, “Who else is going to wear that?” I cut it from top to bottom so I could put it on her like you do a hospital gown. After I got her dressed and sat her favorite chair with a blanket over her legs, I’d give her a spray of Chantilly perfume, which was the perfume she always wore. And I remember my niece came over and hugged her, and she said, “Oh, she smells like my grandma.” Now, I don’t know that my mother knew that she had her perfume on. But other people knew. It’s normalizing the person, so people could relate to her as grandma, and not as this sick person who’s in hospice.

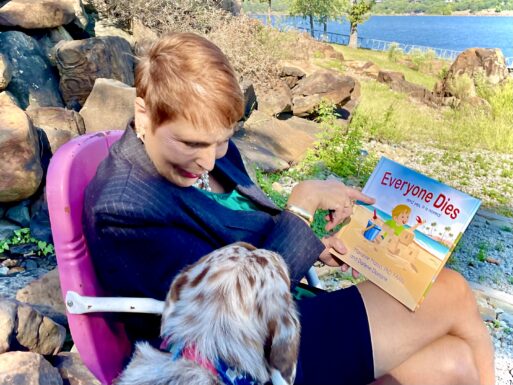

Matzo shows her dog, Luna, her children’s book, titled “Everyone Dies.”

Courtesy of Dr. Marianne Matzo

Are there things that people should avoid doing or saying when their loved one is dying?

Be aware of what they can and can’t do. I had one patient in hospice in New England – the son was taking care of his father, who was getting close to actively dying. And the son said, “Oh, I did something great for my Dad last night. I made his favorite food.” And I thought, “Your Dad can’t swallow.” But I didn’t say that. I said, “Oh, what did you make?” And he said, “I made him lobster, and I fed him lobster.” And I thought “Oh, Lord Jesus.” So I go into the man’s room, and I assess him, and I know in my heart of hearts, that man can’t swallow. So I put on a glove and I swept his mouth, and in his cheeks were these pieces of lobster that I pulled out, because I didn’t want the lobster to sit in there, or for him to choke on a piece. So yes, he’d always liked it, but you have to take into consideration: can he still swallow it?

Also, don’t argue around them. If you’ve got something you’ve got to say, and you’ve just got to say it then, I’m sure there’s some other place in the house or in the neighborhood where you can have that conversation. But you don’t need to have that in the room around a dying person. You just want to be mindful that you’re saying goodbye. I don’t want to be schmaltzy and say it’s a sacred time, but it’s the same kind of sacred time as when a child’s being born. It’s a miracle coming into the world and it’s a miracle going out of the world. So you don’t have to sully that with bad behavior.

Matzo poses with her daughter, Giuliana, and a friend’s baby.

Courtesy of Dr. Marianne Matzo

Caring for somebody who’s dying is a stressful situation. It takes a lot of energy and can be very much a 24-hour thing. And so acknowledging that the people who are doing the caregiving are going to be tired and irritable, and may need some support. Rather than forgetting, or simply not knowing, what’s involved in the caregiving.

You mentioned music, but are there other recommendations you would make for the environment to comfort the dying?

As a hospice nurse, I’ve seen so many different kinds of homes. So I can’t say, “Turn all the lights on,” or “Dim all the lights.” You have to look around the environment at how they normally lived. And if that made them happy, continue to do what made them happy. People want that sense of normalcy. If they always have their fan on, turn their fan on, if they never had it on then don’t start blasting it because you’re hot.

Also, give people the opportunity to say the things that they need to say. We always tell people that there are five things you need to say to people at the end of life, and that is: I love you. Thank you. Forgive me. I forgive you. And goodbye. If you’re comfortable, give them a kiss and say goodbye. And say, “I’m glad you were here, and I’m glad I was here with you.” This is your opportunity to be at peace. Families will often say “When do I do this or that for patients who are dying?” And I say, “Can you do it now?” Because they might not be here tomorrow.

My sister was diagnosed with a terminal cancer, and she really wanted to go down to see her son in Oregon. And she said, “When should I go?” I said, “Can you get tickets for tomorrow?” And she said, “Really? I have to go tomorrow?” And I said, “I don’t know, but I know right now you’re okay to go.” This goes for life in general – if it’s important, go do it.

Matzo speaks at a medical symposium in Korea.

Have you witnessed any particularly touching rituals that might bring people comfort at the bedside of someone who’s dying?

In hospice, we’re not always there right at the very end. I remember going out to pronounce a young woman in her 20s who’d died. And I always say to the family, “Do you want to help clean them up and put their jammies on?” Some people want to do that, and some people don’t. And this family said, “No, you can do that, just let us know when you’re done.” So I did that, and I always talk to the dead person the whole time. Because I don’t know if they’re there. Nobody knows. I just assume that they’re there and that they can listen to me prattling on. After I had this girl nice and clean and her hair combed and all the medical stuff pulled out, I went into the living room, and her mother came in with this blanket. And she said, “This is a coffin quilt. I made it for my daughter when she was diagnosed with cancer.” It was this beautiful quilt – a piece of art. And she said, “I think I’d like to cover her with it now. It doesn’t need to wait until she gets in the coffin.” So the mother covered her daughter with this quilt. I was so incredibly touched. I had a little baby girl, and I thought, “I can’t imagine making a quilt that’s going to go in the coffin of my daughter.”

When I was on the palliative care consult team at the VA hospital, we started a pinning program for the veterans who were dying. We’d invite the family, and we had pins for each branch of service, so we’d look up what branch of service they were in, and our team on the floor would go to the patient’s room. We would thank them for their service to our country, and talk about what we learned from them, or what it was to care for them in this period of their lives. And we’d pin that pin on them, and those who were in the military would salute. We had one young guy, in his early 60s, and his whole family came into the room for the ceremony. And during the ceremony, the son, who was in the military, stepped forward and said, “Dad, I wanted to give you my purple heart.” He took off his pin, and pinned it on his father. Well there wasn’t a dry eye in that room, in terms of the son honoring his father.

So people can take that, and they can adapt that. My mother’s church had a Christian Mothers Club, and they’d given her this pin when she joined sometimes in the 50s or 60s. She always had it in her jewelry box. It might have been nice if as kids we’d gotten together and pinned her.

It’s good to think about, what memories do you want to have? You’re not going to have the person forever, but you’ll have that memory forever. And is it an experience that will bring you comfort, or will it be an experience that you cringe about? Each step of the way, you can ask yourself, is this a memory that I’m going to want to have forever? It’s going to happen to everybody, and so what can we do to make it go as well as possible, and to honor that person and the values of the family as well as possible?

Matzo finds comfort with her dog.

Courtesy of Dr. Marianne Matzo

What can people at the bedside do to care for themselves?

That’s really hard to do. What I’ve seen happen over and over again is that everybody wants to be there at the time of death. Nobody wants to miss the birth, and nobody wants to miss the death. Well, sometimes people have other plans. And more times than I can tell you, people will be doing that death vigil, and they’ll say,”You know, I just really need a shower. Mom, I’m going to go take a quick shower, I’ll be right back.” And when they go to take a shower, or get a quick cup of coffee, or some lunch, Mom dies. And when they come back, they berate themselves for not having been there. What we don’t realize is sometimes people don’t want anybody there. Sometimes people want to protect their kids. We don’t know how it’s going to look, we don’t know how it’s going to be. And so if they can do it alone, people may choose to do that.

You might think, “How do we have any control over that?” I don’t know, but it happens too often to not think that they do. When you work in hospice, there are very few deaths between Christmas and New Year’s. It’s our slow period, because people don’t want to ruin anybody else’s holidays. Or they want to get to a certain age, and they’ll die the day after their birthday. How do they do that? I don’t know, but they do it. So don’t berate yourself. Inevitably, that’s how it’ll go. What I always did, what the other nurses always did, was say, “Go have your coffee, go have your shower, I’ll stay with her.” That way if they die you can say they didn’t die alone. You can say, “She was comfortable, she took her last breath, and that was it. I know you wanted to be here, but maybe she didn’t want that for you.”

Is there anything about comfort for the dying that I haven’t asked, and that you’d like to add?

There are two things that I’ll say are important. One, if people have prescribed pain medicine, give them their pain medicine. Even if you think they’re just sleeping all the time, people might be feeling pain. If they’re playing with their clothes, or with their sheets, that can be a sign of pain.

I’ve had so many families who say, “She never took pain pills in her life.” Well, she never died in her life, either. So if they can be comfortable, let’s help them be comfortable. I’ve had so many families say, “I gave them their pain medicine, and 10 minutes later they died. Did I kill them?” And even nurses ask themselves that – we call it the “last dose syndrome.” They were going to die, it just so happened that it was in whatever minutes of giving them their scheduled pain dose that they’d had 20 times before. So no, you won’t kill them. The cancer or heart disease or whatever illness they have, that’s what’s going to kill them.

The second is about food. You want to nurture people, and one way in most cultures that we nurture people is to feed them. But as I said, we die from the outside in, and the body is looking after its brain and heart. So it doesn’t want to waste time digesting food, and it doesn’t want to use energy digesting food. People who are dying will tell you they don’t want to eat. So that’s something I’d want caregivers to know – it’s stressful for you to be trying to force food down their throat.

When one of my sisters was dying, we spent time going through my Mom’s old cookbook and talking about the recipes and their names – you know, Cecille’s eggplant or whatever. She didn’t want to eat, but we had great fun looking through the cookbook. And we got to the tomato soup cake that my mom used to make, I said, “Do you want me to make this for you?” And she said, “Sure.” It took a couple of hours and I made this cake, and I cut her a small piece because I knew she couldn’t eat much. And she said, “You’re not going to get mad at me if I only eat one bite?” And I said, “No, you can eat as much or as little as you want.” And she literally took one bite. And I took a bite, and said, “It seemed to me that tasted better when we were younger.” And that was it for the tomato soup cake – other people ate it. But let it be the one bite. Other people might get offended that the patient is not eating their food, or they’ll worry that the patient is starving themselves, but that’s just part of the dying process.

Thank you, Marianne, for sharing your wisdom and insight.

Learn more about end-of-life issues by listening to podcasts from Everyone Dies.

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull