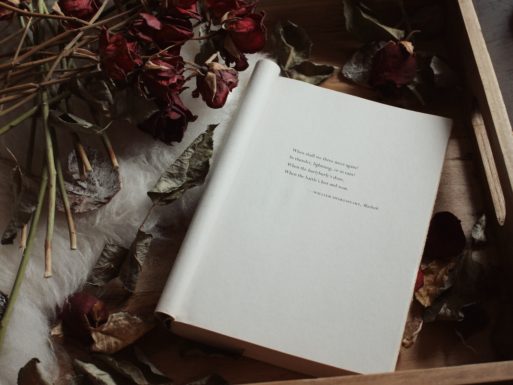

One of my favorite Shakespeare plays is Macbeth, and what’s stuck with me the most over the years is the title character’s soliloquy about life, in the play’s final act. The eloquent passage is cynical, but it makes an interesting point about death:

One of my favorite Shakespeare plays is Macbeth, and what’s stuck with me the most over the years is the title character’s soliloquy about life, in the play’s final act. The eloquent passage is cynical, but it makes an interesting point about death:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing. (21-30)

At this point in the play, Macbeth has been surrounded by so many tragic and horrific events that he has become almost numb. That’s why he sees life as “creep[ing]” (22) past in an automatic fashion; his repetition of “to-morrow” (21) in the first line is proof of this. Macbeth doesn’t believe that any wisdom has come from those that have lived before us. According to him, “all our yesterdays” (24) have led merely to the same, age-old conclusion (“dusty death” [25]). In this dejected view of things, nothing we do in life matters.

To Macbeth, we may feel that we are important, which is why he draws the parallel to actors on a stage, but this isn’t actually the case. We have our insignificant “hour upon the stage” (27) of life and then are “heard no more” (28). No impact is left behind, in Macbeth’s opinion. Everything is quite pointless. His contempt is evident in the language he uses to describe people, from “fools” (24) to “poor player[s]” (26) to “idiot[s]” (29). As much as we may try to make the “tale” (28) of our life sound interesting, it still “signif[ies] nothing” (30).

Despite the fact that Macbeth sees death as a monotonous occurrence, something that happens to everyone and that therefore isn’t special, his main complaint is about life. He would in fact prefer death to life—this is what he means when he cries, “Out, out, brief candle!” (25). Though life is in fact “brief,” that in no way means that we should treat it as if it means nothing; we should make the most of the time we have before it’s gone. But I do see the merit in Macbeth’s calling death a form of relief. In death, there is none of the judgment that comes with “the stage” (27) of life. In death, we are completely free, and I think that’s something we can all agree on, whether you’re cynical like Macbeth, or sunny and optimistic.

- Read a SevenPonds post on one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries

- Check out this recent article on some of Shakespeare’s inspirations

“Macbeth” by Shakespeare

“Macbeth” by Shakespeare

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”