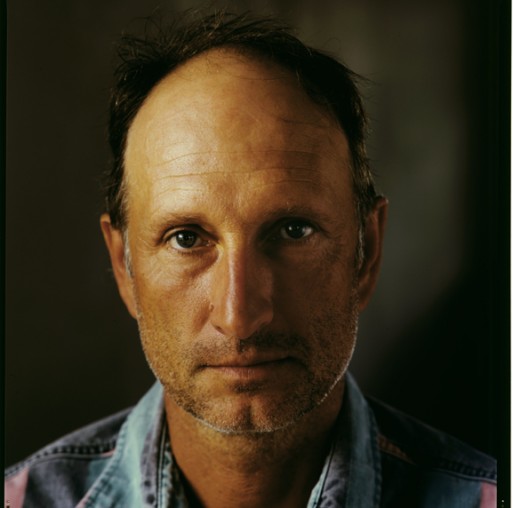

In the late 1970s, Indiana native Bruce Nauman emerged as one of the key players in America’s contemporary art scene. Like many of his peers, Nauman’s art knew no fixed medium – he worked in print, sculpture, video and even performance art to explore the trajectory between life and death. “Art became more of an activity and less of a product,” said Nauman about the development of his style, “If I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art.” Perhaps most memorably, he rendered the abstract (and exhausting) subject of human nature – particularly of our mortality and end-of-life– more accessible through an unexpected medium: neon.

Nauman (whose father actually worked at General Electric) took a blasé medium – that which graces our 24-hour diners and theatre exit signs – only to marry it with the most existential of topics. Take Life, Death, Love, Hate, Pleasure, Pain, (neon, 1983). The words are, literally and figuratively, electrified in a circle that creates a dialogue. Between the six subjects, we find that language suddenly becomes an object. Words like “death” become visible, returning our gaze and challenging us with an internal dialogue we’ve never experienced before.

“Nauman took a blasé medium – that which graces our 24-hour diners and theatre exit signs – only to marry it with the most existential of topics.”

In Human Nature/Life Death (1983) Nauman also juxtaposes weighty concepts in neon, making use of the classic American peace sign to give them shape. It’s an arguably political take on the subject of death, questioning the relationship between death, war and what we often qualify as “the cost of peace.” What better way to discuss the commodification of life and death than through the neon medium that has so successfully marketed so many products?

Nauman’s art is rooted in our quotidian, contemporary experiences; it’s an important reminder that our notion of art shouldn’t be limited to something high-brow. Too often, the word “art” brings up thoughts of stuffy 18th century oils with titles like “Lady Cockburn and Her Three Eldest Sons” that have little relevance to our lives. That’s not to say classical painting is irrelevant, but it’s necessary to keep developing our notions of art. Because as those notions expand, so does our capacity to talk about important topics – like death – from a new perspective.

Related SevenPonds Articles:

- The Goodbye Gallery: A Unique Space for Contemporary Art in the Czech Republic

- “Family Tree” Design Integrates SMS Technology with Urns

- “Die” (1962) by Minimalist Tony Smith

Artist Bruce Nauman and The End-of-Life Electric

Artist Bruce Nauman and The End-of-Life Electric

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”