North America, circa 1831: Irishman Ross Cox had long braved his emigration to America and finally published Adventures on the Columbia River.

The early explorer’s book is integral to our understanding of the era, and not just because it informs us on the infamous American Fur Company in which he was a prominent player. Throughout his observations of the “mysterious Northwest,” Cox’s book highlights the Tolkotin Native Americans of present-day Oregon, expressing his fascination in their rituals for the end of life and burial.

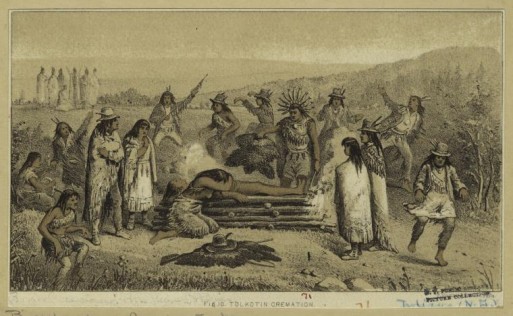

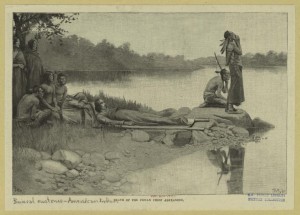

The Tolkotin Native Americans saw the relationship between life and death as a cyclical communion with nature, and their creation myths – a concept that astounded early explorers. “The ceremonies attending the dead are very singular and quite peculiar to this tribe,” writes Cox about Native American perceptions of death and dying. Cox was also unaware of what anthropologists and historians know today: that the Native cremation burials he observed were one of the most pervasive traditions amongst the otherwise diverse Native American tribes of the Northwest.

Although Cox’s understanding of Tolkotin traditions is affected an ethnocentrism common to settlers of the Northwest, we can sift through his biases to find a vivid picture of their cremation burial process:

“The [loved one who has passed] is kept nine days laid out in [the family’s] lodge and on the tenth it is buried. During the nine days the [loved one] is laid out, the widow of the deceased is obliged to sleep along side it from sunset to sunrise, and from this custom there is no relaxation even during the hottest days of summer!

A rising ground is selected [for the cremation], on which are laid a number of sticks, about seven feet long, of cypress, neatly split. Invitations are dispatched to the natives, requesting their attendance. When the preparations are perfected, the [loved one] is placed on the pile, which is ignited…during the process, the bystanders appear to be in a high state of merriment.”

Finally, the loved one is buried and tended to by their surviving spouse, so as to “keep [it] free from weeds.”

In his book On Our Way: The Final Passage Through Life and Death, Robert Kastenbaum makes some pointed observations about the Tolkotin Native Americans, and what we can learn from their perception of cremation today. It’s odd, writes Kastenbaum, that green cremation “still strikes people as being new, improper, profane, and dangerous” when “cremation has [had] solid credentials in history and the current scene. Fire was exciting. Fire was powerful. Fire purified. Fire was magic. Fire was a gift from the gods. The mystery of life, the mystery of death, the mystery of fire!”

Kastenbaum’s point is resonating. There are manifold businesses playing their part in the growing movement for natural or “green” burials in the US and Europe, many of which embrace cremation burials. The Tolkotin Native Americans had no access to formaldehyde or other eco-unfriendly elements – but they probably wouldn’t have wanted them anyways. The cremation rituals for end of life and burial practices come down to one overarching goal for these Native Americans: that we respect the planet that has given us so much – especially in the way we choose to look at our own death, and dying process.

Related SevenPonds Articles:

- Wampanoag Burial Traditions

- Our film review of the Native American film “Smoke Signals”

- Reflecting: What American Indian Burial Traditions Can Teach Us

Tolkotin Native Americans: Rituals for the End of Life and Burial

Tolkotin Native Americans: Rituals for the End of Life and Burial

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville