Death, so they say, is inescapable. It is a private affair that plays out in public, and the depths of grief follow the same shifting landscape of public and personal.

A death is marked in the public sphere in obituaries, through public services, rituals and tombstones or grave markers. Often there are publicly prescribed sites, whether legally or culturally commanded, for when and where grieving and marking a death can take place.

These social structures can provide solace, a psychosocial infrastructure for the emotional chaos of death. Sometimes those structures become confining, and healing comes from a space that exists outside of social or legal norms. For instance, alongside a public highway.

Roadside memorials are a global phenomenon, but there are particular places where they have flourished. The Southwestern region of the United States is one place where they have blossomed.

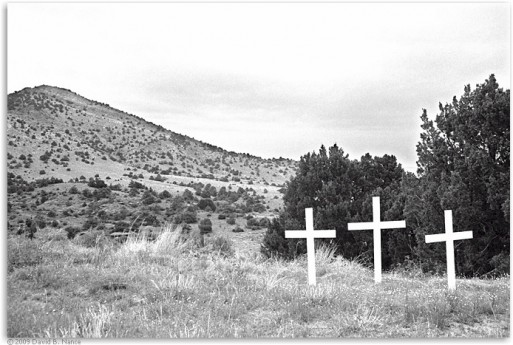

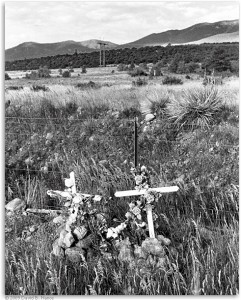

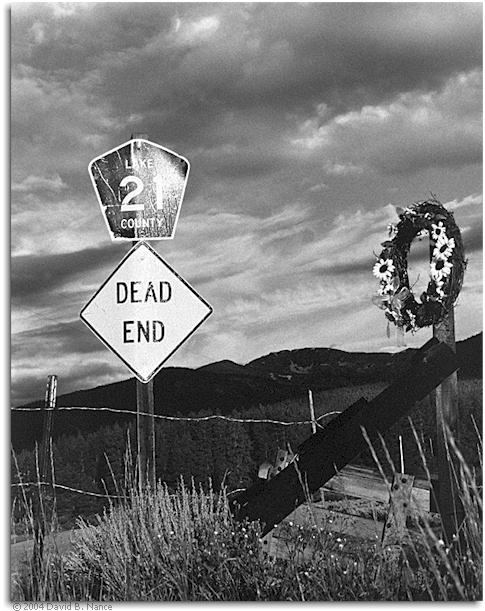

Scattered along the highways of the American Southwest, ad hoc memorial sites mark loss of life. Dave Nance documented these memorials, known as descansos, in his photographic series of the same name. His black and white images offer intimate portraits of moments of intense loss in time and space.

Nance would do something that many of us don’t as we pass these memorial sites; he would pull over and take a photo. He would make contact with the memorial, experiencing the sites in a way that was one step removed but still emotionally connected.

These sites mean something profound to the people who erected them. This place changed their lives in a way that a sudden death changes everything.

The sites end up serving multiple intentional and unintentional purposes, allowing a grieving family to acknowledge the place of loss while announcing the real dangers of driving. They strongly state the importance of remaining vigilant and aware of how quickly everything can change, as you whiz by at 70 miles per hour.

As seen in Nance’s black and white images, the memorials follow their own visual logic as idiosyncratic applications of religious and cultural forms. There are typologies that can be described, such as the frequent use of iconic white crosses with hand-scribed names. The crosses communicate immediately what they broadcast, but the memorials can take any form — there are no rules.

Personal effects often adorn or surround the memorials, either at the base of the cross or hanging from a structure. Stuffed animals, cigarettes, candles and plastic flowers add intimate details to the story of the lost life.

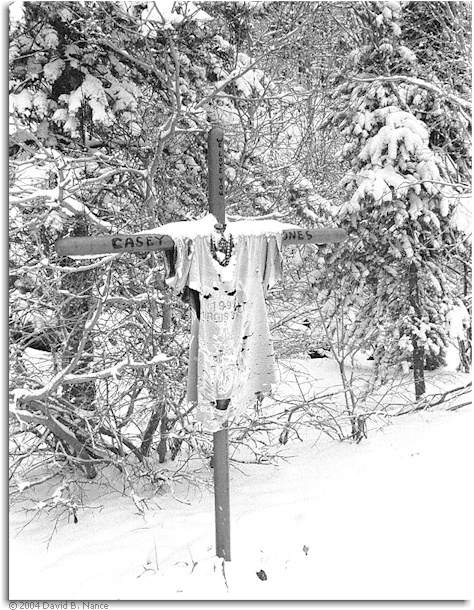

In one photograph, a shirt hangs in tatters from a cross and the name “Casey,” written in black, slowly comes into view. The eerily physical, shirted form becomes complicated by layers of snow, bringing to the surface the impossibility of a living form underneath.

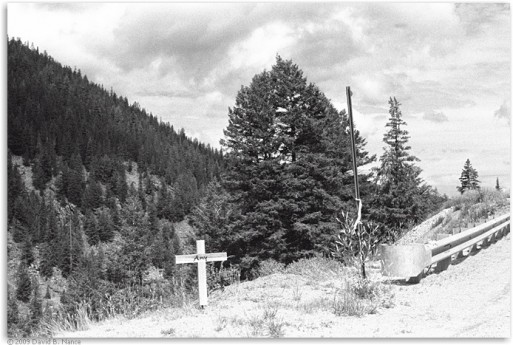

In another photograph, only a first name — Amy — marks individuality. The personal items that surround other memorials have a particular poignancy, but the solitary first name touches on the challenge of putting loss into words; Amy’s trace remains abstract, ripe ground for us to inject our own grief.

The Southwestern memorials have historical tracings in Catholic funerary rites practiced in the new world. A body would be carried from the church to the graveyard by men, who would stop at some point along the journey to take a rest. The resting point would be marked with a white cross or flowers. The “resting places,” translated from descansos, then took on an additional layer of meaning as the stopping point of a physical life in the journey towards death. The marking of that point, where the soul continues its journey in a different form, becomes hollowed ground for loved ones, a final resting place that often takes on more significance than the burial site.

By documenting these memorials, Nance also contributed to their continued life. At the time he documented them, the roadside memorials were illegal, and were only erected for a short period of time only to be quickly removed by authorities.

Several states, including Colorado, have dealt with the practice by establishing state-sanctioned markers. The Colorado markers have the name of the person who has died and a statement: “Please drive safely.” In other states, the practice in all forms is entirely banned.

The state-sanctioned memorials lack the heart of their ad hoc predecessors. Their formality upholds the public service announcement, but they blend into the landscape of signs telling you to stay within the lines.

By falling outside of the lines, the descansos surface death at every turn. On his website, Nance offers a fitting quote from Marcel Proust:

We say that the hour of death is uncertain, but when we say this we think of that hour as situated in an obscure and distant future. It does not occur to us that it can have any connection with the day already begun or that death could arrive this same afternoon, this afternoon which is so certain and which has every hour filled in advance.

This encompasses the discomfort that these very public, personal descansos announce as we make our own journeys through space and time towards that inescapable end.

Photographs by Dave Nance used with permission for noncommercial use.

Marks the Spot

Marks the Spot

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition