Today in this interview, SevenPonds speaks with Pashta MaryMoon, Death Midwife at Journeys Beyond, and co-founder of CINDEA (Canadian Integrated Network of Death Education and Alternatives). Pashta lives and works in Victoria, BC, Canada.

Juniper: What is a Death Midwife? What services does a Death Midwife offer?

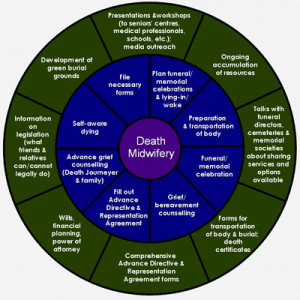

Pashta: In North America, the term “Death Midwife” is often used rather loosely to refer to anyone involved in alternative dying work. I use it as a very specific term that identifies someone who can provide a continuum of services across most of the seven stages of the pan-death process. There are many parallels to Birth Midwifery — home-based, active/hands-on involvement of the family, the basic philosophy, and especially in terms of having a trust-based relationship that spans the time of the whole birth or death journey. A Death Midwife, for example, may or may not be involved in advance care planning, but they would definitely be available as soon as someone knows they are moving toward death, whether that be receiving a terminal diagnosis, or being told they have a life-limiting illness. Throughout that whole process, all the things that that person may want to do in their remaining time can be planned with a Death Midwife’s help, right through to the active dying stage. A Death Midwife can also facilitate a home funeral, if that’s the family’s choice, as well as a ceremony around internment or spreading of ashes, grief support, and ceremony to mark the one year anniversary following a death. So, I only use this term “Death Midwife” for someone whose practice encompasses this broad spectrum approach and offers their services throughout its entirety.

The image by which Journeying Beyond, Pashta’s Death Midwifery service, is recognized

(Credit: beyonds.ca)

Juniper: You’re the co-founder of CINDEA: the Canadian Integrative Network of Death Education and Alternatives. What is the purpose of CINDEA?

Pashta: CINDEA is a non-profit organization born from my own research as I began investigating Death Midwifery. As I was collecting resources for my own practice in British Columbia, I often came across useful ones for other provinces as well; and kept track of them, being sure that eventually someone would need them. When CINDEA was later created, one of its major projects was to fill out those resources for each province/territory and make them available through the website. Over the years, CINDEA has cultivated a network that includes the Slow Medicine movement, the Right to Die movement and the National Home Funeral Alliance in the States. It also includes some resources in the UK and Australia, in recognition that we live in a global community and have family (blood-relations and chosen family, including close friends and spiritual community) all over the world.

CINDEA realizes that it will be at least a decade before Death Midwives or related support services are available, even in most urban centres across Canada. So, CINDEA supports people in several ways: for those who are interested in practicing Death Midwifery, it directs them to training resources that are accessible to Canadians; for those interested in caring for their own, it provides simple, practical advice and information necessary to do that – from filling out and filing paperwork to preparing a body for a home funeral. People accessing CINDEA for the latter purpose will likely be working with a palliative care team, and may need a grief counsellor or other professional aid afterward, but at least they will have the ability to do a home funeral on their own. CINDEA also has a strong commitment to ecologically responsible practices. There’s a lot of information about green burial, including up-to-date news on the availability of aquamation (alkaline hydrolysis), the use of shrouds and ‘green’ caskets. We are working towards a Canadian company to produce 100 percent recycled cardboard caskets.

Juniper: What is the Slow Medicine movement?

Pashta: It’s an approach that sees certain kinds and quantities of medical intervention at the end of life as unnecessary in the sense that they do not support quality of living or quality of dying. So, that would include decisions like having fewer surgeries to prolong life, foregoing palliative chemotherapy and reducing the number of medications taken. When an individual is taking more than four or five medications at a time, then more medication is needed to treat the side effects of those initial prescriptions, which puts undue stress on an already frail body.

Slow Medicine also focuses on making the hospice and palliative care environment more humane, which includes training doctors in end-of-life issues (right now they get only an hour of training in their curriculum). We are fortunate that within the last five years or so, we have seen a progressively rich body of articles and books produced by doctors and palliative care professionals about why they are pulling back from the med-tech default approach, which is to apply all treatment options possible. Currently, it’s felt that if someone dies, it’s a failure of the medical industry, not a natural conclusion of having lived.

The Facebook page for the Slow Medicine movement is run by a woman named Katy Butler, who wrote the bestselling book Knocking on Heaven’s Door, which recounts the story of her father’s final years suffering through dementia and physical pain as a result of having a pacemaker put in unnecessarily. Slow Medicine is about encouraging holistic approaches to wellness, but its main focus is on preventing unnecessary medical intervention like surgery and drugs, and making the whole end-of-life experience much more humane.

Juniper: Tell us about your personal journey to become a Death Midwife: your experiences, inspiration, teachers.

Pashta: When I was seven years old, I was watching TV when I wasn’t supposed to be. It was one of those stereotypical Cowboy-and-Indian movies from the ’50s. There was this pioneer family setting off into the West in a covered wagon – you know, a husband, wife and a couple of kids. They get attacked by a group of “Indians” and the husband gets killed. The wife has no other choice than to clean him up, dig a grave, put him in it, fill it in, get back in the wagon and carry on with the kids, because they were already in the middle of nowhere. I left that movie feeling like that’s the way it should happen.

Since then, in every decade of my life, something drew me back to death. In my thirties, I took a degree in World Religions and Jungian psychology, doing a lot of research into cultural attitudes toward death, particularly in the western world. During the same time, the AIDS crisis happened. I was involved in a lot of support groups for people who were dying of AIDS, caring for some of those people as they died, and then doing funerals and memorials for them. In the 1990s and 2000s, I spent several years working in prisons with “lifers” who go through a process very similar to the five stages of grief outlined by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. Also in the 1990s, I was the very first non-Christian on the spiritual care team at my local hospital in Victoria. I spent a lot of time on the renal ward, where you know that about half the patients are going to die soon, because their kidneys are failing and dialysis has stopped working for them. In the 2000s, I started a Bedside Singing and training program with another woman in the hospice unit at that hospital. Afterwards, I began working privately using vocal music to support individuals with later stage dementia and/or who were actively dying.

One of my greatest teachers is Jerrigrace Lyons of Final Passages. When I connected with her in 2005, I realized that I already had experience in all of the pieces that are involved in being a Death Midwife, except for the actual practical part of a home funeral. Jerrigrace was very generous: I wasn’t able to travel to study with her, so she sent me lots of materials, as did other people, as I began sharing my process. Eventually it occurred to me that I had all seven stages of the pan-death continuum covered – I’d worked in counseling; I’d worked with grief; I’d worked with people before their death and I’d organized and led funerals and memorial services for a lot of people with very different cultural and religious backgrounds. In 2013, Jerrigrace was coming up to visit family in the Pacific Northwest, and she trained me in person while she was here. Ken Wilber’s work in the 1980s was also significant for me.

Juniper: Why is Death Midwifery important?

Pashta: The pan-death process is a difficult time for family. Even when a death is expected, it’s still a shock when it happens. There are two main ways that a Death Midwife can help. The first is to help navigate ideas around death, encompassing quality of living but also quality of dying. The medical community is still life-biased and talks about quality of life right up to the moment of death. They never talk about quality of dying, but to me it’s a balance of both. And then home funerals, they have a hands-on approach that is participatory and very helpful for family in their grief process.

I believe that there is a need for consistent support across the entire pan-death continuum, because the reality right now is that you get connected with hospice, and that’s great because they are very supportive, but those individuals don’t work 24/7 so there will be different nurses and home care people coming in who don’t know the personal history of the Death Journeyer and their family dynamics and personal preferences. Then, after death, the family needs to deal with funeral directors and other professionals who have no idea what they’ve just been through and who often do not have the same philosophy. There’s a big gap there. So there’s a real value in having a person like a Death Midwife accompany a family throughout the entire continuum. You might see them more after the death when they come in to organize a home funeral and do a memorial service, but they’ve been part of the story before the death, know what’s happened and what the death was like, what the dying was like, what the family baggage is. A Death Midwife is trained to recognize when the family is tapping into ideas that are really meaningful for them and how to cultivate that in such a way that is helpful to everyone. By guiding a home funeral, which has a very hands-on and participatory approach, the Death Midwife can support the further drawing-out of elements of personalized meaning, which itself tends to deepen the family’s grieving process.

Many of the pieces of the continuum are already offered by individual services, some of which are progressive and more humane, but they are often not linked in practice or in philosophy. Therefore, there is a benefit in having a single person to walk through the whole journey with you. A relationship with a Death Midwife is built on a foundation of trust, so that the family feels comfortable communicating what’s really going on and what is wanted. I think that that is really important. In the system that we have now, despite all our compassionate professionals, people still get abandoned because they haven’t had the chance to build a relationship with a care provider in which they can go to the depth they need to in order to have a meaningful death. This is what I mean by “quality of dying.” Some people in the North American alternative deathcare community claim that in about 20 years time people won’t need Death Midwives because there will be so much information accessible that they can just do everything themselves. However, death is a major life transition, and I believe that nobody should ever have to go through it by themselves unless they choose to.

Juniper: You teach a workshop called By My Own Heart and Hand — Basics in Home Funerals. What is a home funeral? What topics and skills are covered in the workshop? Is there any pre-requisite for attending?

Pashta: There’s no pre-requisite at all. The only thing you need is to be interested in the concept of being more hands-on around death. Taking more individual responsibility around it. That doesn’t necessarily mean you have to do a home funeral; some people come to investigate the concept and challenge their own taboos. A major piece of the death taboo is the “ick” of handling a dead body. In the workshop, there is a live model who pretends to be dead so that everyone can see and practice the washing and preparation part. I make sure people are in the right mindframe before we come around to actually doing it.

A home funeral is essentially the process of a family doing the physical post-death care, the required paperwork, and making arrangements for the disposition of remains by themselves (sometimes, but not always, supported/guided by a Death Midwife, Home Funeral Guide or similar practitioner). This process lasts an average of three to six days, though every situation will be unique. It will often include ceremonies that are either planned, or happen spontaneously. It’s very common for people to start doing the post-death care as a practical thing, and find that in the process, it becomes a sacred act. Many, many people have commented on that – even in the workshop, when they know it’s not a real dead person.

The workshop is focused on practicalities. We don’t much get into the ceremonial side of it, because it would take far too long and there are so many possibilities. The workshop is comprised of two parts. There is always an evening viewing of the film A Family Undertaking, followed by a discussion period to get people comfortable with each other. The next day, in the morning, we discuss timelines: what needs to be done and when. That includes reviewing the paperwork that needs to be filled and filed, where to get it and who to send it to. We also discuss moving the body around the home, taking into consideration structural issues like the width of doorways and elevators. You’ve got to take a body down an elevator in a shroud, and place it in a casket – if you’re using one – on the ground floor. Caskets just don’t fit.

The afternoon is spent doing the hands-on part of post-death care. The people I know who are running this kind of workshop in the USA tend to go through this part rather quickly, and demonstrate on clothed models. I feel very strongly that it’s important to work with as naked a body as possible, and that we do every inch and crevasse. That’s the point at which the people in the workshop really start tuning in to the emotional value of this practice. This is when the shift is felt from the practical to the sacred. Everyone who has modelled as the dead person has also felt that they’re being cared for in a really tender, careful, sacred way. That wouldn’t happen if people were pretending over clothing. I always run this workshop in someone’s home (as opposed to a meeting hall) because I want people to be thinking, “If this was my house, what are the dimensions of my hallways? Do I have an extra shower curtain or tarp to use as a drop cloth while washing a body? What would I be doing and thinking and feeling at the various stages of this process?” The setting helps participants to connect psychologically and emotionally in a very personal way, with an emphasis on doing this in their own time, finding meaning and purpose in their own way.

Home funerals are also a more ecologically responsible and low-cost alternative to turning over a body to a funeral home, where many unnecessary chemicals are used to clean and embalm, not to mention all the single-use rubber gloves, paper sheets and product packaging. People would be utterly shocked to know how much waste is produced in that process. Unless there is the presence of infectious disease (pneumonia, for example), rubber gloves and masks aren’t necessary. When post-death care is done at home, you use a lot of the same things you used to care for your loved one while they were alive: the same sheets, shampoo, towels. A lot of things you need are already right there in your home, and they’re things you use on a regular basis. Additionally, to keep the body cold over the duration of the home funeral, I recommend using Techni Ice – which is reusable – instead of dry ice.

Pashta MaryMoon demonstrates how to roll a body so it can be washed and prepared for a home funeral

(Credit: plus.google.com)

A traditional funeral organized through a funeral home can cost upwards of $5,000 to $10,000 if you include a casket, chapel ceremony, the whole thing. The cost of a very basic home funeral is almost nothing, but you still need to take into account the disposition of remains, including whether a shroud, basic cardboard or wooden coffin is used, whether it’s from a large supplier or handmade by an artisan, etc. I know a family who recently released cocooned butterflies as ashes were spread – that’s several hundred dollars right there. It’s entirely up to the family, and there are lots of factors. But generally, a home funeral is much more economical. If you’re working with a Death Midwife, they will likely charge a fee. Personally, I charge $1,200 for a guaranteed minimum of 25 hours of service, which includes a funeral and/or memorial service and initial grief support. That’s on par with what you’re charged when you walk into a funeral home to make basic arrangements – without the embalming, visitation, funeral, coffin or anything. And you get about three hours of their time.

Even though using things you already have in the home is more cost effective, there’s also something very meaningful about using the same towel that you always used to dry off Mom after giving her a sponge bath. When you use that towel for the last time to clean her body, that can create a sense of closure that is very helpful in the grieving process. For primary caregivers – usually a member of the family – there is great benefit in participating in post-death care. That person has been orienting their life around caregiving for weeks, months, probably for years (because of medical technology, our dying is so prolonged these days). For however long they’ve been caregiving, even if they’re still working and have other responsibilities, they’ve built their lives around the needs of the dying person, even when residential care is involved. That only covers the basic physical aspect. The family caregiver is still making sure that their loved one’s needs are getting met – that they have appropriate clothing, enough toothpaste, that they’re going outside to enjoy the world and can still see through their glasses.

Caregivers never know when the last act of caring will happen, so when they participate in a home funeral, they are guaranteed one more opportunity to offer an act of love, care and respect after their loved one has stopped breathing. If a body goes to a funeral home, usually an hour after death, a caregiver’s sense of identity and self worth are suddenly gone, and they’re left with little opportunity to shift out of their role. Over the duration of a home funeral, there is the opportunity to do that. Yes, the Techni Ice still needs to be replaced, but that’s the only major need.

There is also the chance to realize that the person they loved is no longer in the body, so that by the end of the home funeral – if things are happening in a healthy way – they’ve emotionally disconnected from the body. When a body is taken away an hour after death, the body and the person who used to inhabit it are still associated with each other. These days, open casket funerals are becoming less and less common, so fewer and fewer people are having that chance to go through that healthy dissociation process, which is needed not just for caregivers, but for everyone who had a relationship with the deceased.

There’s also the matter of resentment and guilt in the family – particularly guilt around how caregiving often falls to a particular person. A home funeral gives other family members a chance to do some of the caregiving and organizing, which helps balance things out a bit.

Juniper: How do you see the role of the Death Midwife in facilitating community cohesion?

Pashta: Natural grieving goes through several stages and takes many forms. There are tears and sadness; anger at the situation, the dead person, and oneself (all the things you could have done but didn’t). But then there’s laughter, and the need to deal with mundane things, and nothing unfolds in a pre-determined order. But it goes like that, moving in and out of intense emotions. That’s healthy grieving. When you’re doing a home funeral, sometimes the tears just pour, but then someone might drop the toothbrush being used to clean their loved one’s teeth, and everyone will start laughing. Then someone will need to go get another towel because there aren’t enough, or put on a pot of tea because everyone has been washing the body, standing for a long time, and singing, and their voices are giving out, and they’re tired. There’s also the tasks of doing paperwork, feeding people, greeting visitors… there’s a rhythm that unfolds in those three to six days, going into and out of different kinds of emotion. It’s much healthier than just being in grief, or just in “crisis calm,” which is what most people default to after a death. This is a kind of numbness or shock, where tears spurt up once in a while, but mostly the emotions are cut off. This is a survival response that allows people to deal with practical things. But in a home funeral setting there are several people doing organizational tasks, and there’s time to feel, and people to witness and mirror those emotions.

In our culture, we are so isolated in grief. Most employers give a maximum of two weeks bereavement leave, and then it’s back to work like nothing’s changed. No one wants you to cry in front of them, and you might not want to cry in front of anyone else because they may still be grieving a loved one and you might trigger their tears – and we’re not supposed to make people cry. No one wants to talk about it or let it happen, so all that emotion gets held inside. That you’re grieving the loss of a relationship in isolation from your remaining relationships makes the wound even deeper. When you have that three to six days to cry, laugh, do mundane things, go out and play basketball then come back and cry some more, there’s a community of grief created where everyone has permission – to grieve, yes, but also to laugh, be angry, be relieved. That’s a big one in our culture. You’re not allowed to say, “My mom finally died and I’m so relieved!” And we are not allowed to say to people who have been caregiving for a long time, “I’m so glad that your mom died – that she’s released, and you’re released.” Yet, that’s a reality.

It didn’t used to be the case that people had a prolonged dying over several years, but now it’s common and we need to give each other permission to acknowledge that. The foundation of this permission is built during a home funeral, but it extends beyond that. People feel like they’re able to call each other up and be received when they’re having a hard day and grief is really present for them. There is none of that common fear that when someone goes into grief, they may stay there forever, get highly depressed and commit suicide. Because they’ve already experienced and witnessed in each other that cycle of emotions, they know that they will be able to carry on with the rest of their lives after a moment of catharsis, so it’s okay to let it happen. This also makes it a lot easier to plan things like what you’re going to do with your loved one’s ashes. There are so many boxes of ashes sitting in the back of closets because the family won’t get together to talk about it out of fear that they’ll prolong the grieving process. The one-year anniversary of a death can be even more emotional than the initial loss, so when permission to grieve is already established, it can make that experience more meaningful and helpful for everyone.

Juniper: When you facilitate home funerals, do you find that the family members who could prepare a body after death are interested and willing to do so? Do you encounter any squeamishness? If so, how do you navigate through that?

Pashta: Yes. This is one instance in which a Death Midwife can have an important role. We are so culturally trained out of caring for our dead that we believe it’s illegal, repulsive or simply not possible. The moment someone dies, the executor has control over the body, so it’s important to have them on board with the concept of a home funeral in order to give the whole family an opportunity to experience it. If the executor hasn’t been a primary caregiver, then they’re likely not the person who wants a home funeral. I had this situation come up recently. My role was to talk to the sibling who was the executor, to reassure her that yes, I’m an expert in home funerals, yes it’s legal, I know about all the needed paperwork, no you don’t have to contact a medical doctor immediately after death, and that yes, this is all very workable. I have the authority to say these things and be received, whereas there may be an assumption between family members that their knowledge comes only from personal research into unverified sources. My role is to explain the details, and affirm how simple and realistic this all can be. Sometimes this convincing works, and sometimes it doesn’t… Sometimes the executor doesn’t show up in time, and the people who want to do post-death care themselves just go ahead and do it.

Another related issue is around the education of other professionals. If a hospital or residential care center won’t release a body into the care of the family, or if a cemetery doesn’t know that a family can legally transport the remains of their loved one themselves, then a Home Funeral Guide or Death Midwife is needed to advocate on the family’s behalf.

Juniper: Do you have any recommendations for people to communicate their desire to organize a home funeral to other members of the family who may be resistant to the concept?

Pashta: In the USA, a good starting point is the National Home Funeral Alliance website; in Canada, look up CINDEA. Once you’ve discussed with your family the reasons why you want to do a home funeral, and you’ve gone to a reputable website where everyone can see that it’s legal, possible and not that hard to do, sometimes mediation is still required. That’s when it’s a good idea to find somebody in your state or province who has a background in alternative death education – they may not be a practicing Death Midwife, but they can be a good resource. There are many ways in which people are using their training, and I encourage the public to avail themselves of it. It’s not worth getting into a family feud over this issue – there are better ways to move through grief.

Juniper: Why do you think there is such a taboo around death in our culture?

Pashta: There has always been a taboo about death, but it’s been dealt with through ritualistic provisions. Loss of life: that’s a big thing. In a way, it’s bigger than birth, because you don’t know the person who’s being born, but you know and are attached to the person who has died. In the West, we’ve lost a lot of traditions that mediated the fear of death. Contributing factors include the American Civil War, shortly followed by the First and Second World Wars. Embalming became commonplace as families wanted to bury their dead at home, necessitating the preservation of remains over distance. The practice of embalming soon became an institutionalized status symbol, along with having a fancy coffin and a lot of flowers. In some ways, it’s no different than eating white bread. Why did we ever start? For no other reason than that it was at one time a status symbol.

Another factor is that many people living in urban centers are not living in operative communities – they don’t know their neighbors, and can’t call upon them in times of need. So of course they’re going to call the undertaker and funeral director instead, because they can’t do it alone. The more urbanized our lives are, the more institutionalized our lives and deaths will be. This is what the situation has become, but it doesn’t need to be that way.

Juniper: What is the greatest challenge you face in your work?

Pashta: The biggest challenge is the death taboo in our culture. It’s deeply ingrained, though only a couple generations old. I know people in their 30s who have stories of their grandparents taking care of their neighbors’ dead bodies. That “ick” factor is really strong though, and can be a complete block. There’s a lot of education that needs to be done, and CINDEA attempts that partly through the videos that can be found on the website depicting, step-by-step, how to do post-death care.

The other challenge comes from the funeral industry. While hospitals and residential care facilities may not know that home funerals are legal, funeral homes do, and they market their services in a disempowering way that insists they are the only ones skilled enough to deal with dead bodies. In the USA, there are some states where the funeral home industry has pushed through new regulations that have effectively cut off the practice of home funerals. One regulation necessitates that all the paperwork needs to be filed electronically; while it can be accessed online, printed out and filled by family members, only funeral homes can file those documents out electronically. So, even if a home funeral is done, the paperwork needs to be taken to a funeral home to be filed, and the funeral home charges them a full arrangement fee – anywhere from 1,000 to $3,000 for two or three forms.

Juniper: How do you envision the practice of Death Midwifery evolving over the next 10, 20, 50 years in North America?

Pashta: Baby boomers tend to separate themselves from tradition of any sort in favor of doing things their own way, so, as more of them are starting to make arrangements for their own parents, I see home funerals becoming much more commonplace. The ecological impact of traditional post-death practices in the West will also be a deciding factor for some people. Although I don’t believe we’ll ever get away from the status issue of traditional funeral care, I see a new kind of status arising around people who do home funerals and green burials, as the public becomes aware of their lighter carbon footprint.

I don’t think we’ll ever see a time when the services of funeral directors won’t be needed. There will always be people who don’t want to deal with it, and there isn’t always a home to bring a body back to. In some instances, a person who is living in residential care has family living in elsewhere in the country or the world. As hospice and palliative care evolve in their awareness of the overlap between their practices and home funerals, I hope to see “lying-in” rooms within those institutions where there will be an opportunity for a family to wash and dress the body, receive visitors and do some of the things that make a home funeral so powerful. Two to four years is the average amount of time that a person living in residential care will be there, and over that time relationships develop with the other residents. Right now, when someone dies in residential care and their body is taken away an hour later, the other residents and staff don’t get a chance to say goodbye — no one invites them to the funeral. So these lying-in rooms could provide a context for family, other residents and staff to mourn, to be witnessed and supported by each other. This is the longer-term, 10-20 year projection.

As more people learn about how they can take the care of their dead into their own hands, we’ll start to see funeral homes offer individual services to round out what a family doesn’t wish to take on, such as the transportation of remains, or the filing of paperwork. This is already happening, and I think it’s a wise move.

Juniper: Thank you so much for sharing your experience and insight with us. It’s been an honor.

Pashta: Thank you!

Why is Death Midwifery Important? An Interview with Pashta MaryMoon, Part One

Why is Death Midwifery Important? An Interview with Pashta MaryMoon, Part One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead