Project Nighlight

Credit: Scpr.org

Today SevenPonds speaks with Cassandra Christensen, a retired R.N. who discovered her life’s mission was to work with people facing the end of life. After working as a staff nurse at UCLA, Cassandra transitioned into private duty nursing. It was at that point in her life that a chance encounter with Mother Theresa catalyzed Cassandra’s work with AIDS patients. With the help of Marianne Williamson she founded Project Nightlight, through which they trained thousands of volunteers to go into the community and provide emotional support for those dying of AIDS. Decades later, Cassandra teaches workshops and trains people how to be with the dying.

Ellary: Cassandra! Thank you so much for taking the time to chat with SevenPonds. Could you start with a little bit about your background?

Cassandra Christensen: I’m a retired R.N., and I worked at UCLA medical center for a number of years in the late 60s and early 70s. While I was working there, the head nurse would always assign me to patients who were dying. She just thought I was really good with dying people. After working there, I went back to school and got my bachelor’s degree in psychology and started writing and giving talks on how to “be there” for the dying — how to be a midwife to the dying. I lived in New York, and the AIDS crisis was going on at the time. I did home care with AIDS patients, and then I moved back to LA and did home care with AIDS patients here.

Ellary: What was it about your disposition or orientation that made you good with dying people?

Cassandra: Well, I love hearing stories. And, I know it probably doesn’t sound good when I say it, but I love to be with people when they’re in crisis. I just think that everything’s real then. The heart’s wide open, and it’s almost the most sacred time of life. I like to be with families, gathering families together and finding out what they wanted for the person. Sometimes families have great schisms and rupturing of relationships, and everyone’s on a different page. I just love the whole process of being with people and sorting things out when they’re really close to dying. I also love teaching people, inspiring other people to be there with the dying. I’ve been doing a lot of teaching and support groups in the past few years.

Ellary: I know it was Mother Theresa who encouraged you to work with AIDS patients. At what period in your life were you when you ran into her and how did that encounter happen?

Cassandra: Well, in the 70s I knew someone who was the casting director for “The Dating Game,” which was a lot like “The Bachelor” but simpler. She asked me if I’d like to be a chaperone for “The Dating Game.” My job as a chaperone was to take the winning couples all over the world. So, I took this couple by the name of Theresa and Kevin to Bermuda. And on our way back from Bermuda we were running to catch the plane because we were late. We were running through the concourse and I lost them and started calling out, “Theresa! Theresa!” And who turned around but Mother Theresa! She was surrounded by a bevy of nuns and I went up and took her hand and shook it up and down saying, “Oh, Mother Theresa, I’m Cassandra and I do the same work as you!” Meanwhile, the other part of me is thinking to myself, “Are you kidding? You don’t take anybody in off the streets of Calcutta! And you’re a groupie for God’s sake!”

Cassandra and Mother Teresa

Credit: scpr.org

Anyway, I finally caught up with the couple, Theresa and Kevin, and put them on the plane. Then I went back to the concourse and talked with Mother Theresa, who was at that point sitting with the other nuns in a semi-circle. She said, “So, tell me what you do.” And I said, “Well, I’m there for people when they’re really close to the end of life.” And she said, “Do you work with AIDS patients?” I went, “well, kind of…” It really wasn’t true. In fact, I was running a cable TV show where I’d invite families on to interview them about being with their dying loved ones. I’d had one moving experience interviewing a couple who had a profound experience with their son who was dying of AIDS. That was really all I did.

I was kind of homophobic at the time. I didn’t figure out that I was gay until 10 years later when I fell in love with a woman and figured out why my previous marriages to men hadn’t worked out!

Anyway, Mother Theresa responded by saying, “You, you work with AIDS patients!” So I came back to LA. Then Marianne Williamson, who had heard about my Mother Theresa story, said, “I”ll help you do the work.” So we created a space for people with AIDS to hang out at the LA Center for Living, which helps people with life-threatening illnesses. And from there I developed my non-profit, Project Nightlight. For a number of years, we trained volunteers to go out in the middle of the night to hold people with AIDS in their arms, when not even the parents were willing to be there. That was true in a lot of cases. Parents refused to be there, and their sons were dying alone.

Ellary: You said you were dealing with some internalized homophobia prior to coming out yourself. But after your talk with Mother Theresa, your focus became working with gay men dying of AIDS. What shifted for you?

Cassandra: Before I met Mother Theresa, I felt that nurses should be paid extra to work with AIDS patients. So I was kind of cold-hearted. But actually, just being with her caused me to shift. I wasn’t like that ever again. And, of course, eventually, it became very obvious to me that I was gay.

When I started working with AIDS patients, I discovered that I loved providing support for these men. Their hearts were so open. There was a huge shift in how we were with patients because of the AIDS crisis. Volunteers would get in bed with patients and hold them while they were dying. There was so much love. It was just amazing to be there for that. At that time I was teaching and training and supporting rather than going out in the night to do the direct work. Marianne got huge numbers of volunteers to go out and do that. Project Nightlight was under an umbrella with Project Angel Food, a non-profit she developed that goes out to deliver food to people with life-threatening illnesses. During the AIDS crisis, Project Angel Food focused on providing meals for people dying of AIDS.

Ellary: What followed Project Nightlight for you?

Cassandra: Well, about three years ago that I realized that I was an alcoholic and joined AA. I started going to the Unitarian Church. Both of them had the same goals: love and service. It inspired me to return to this. I ran an almost-year-long program on death at the church. We met from two to four or five times a month and dealt with all kinds of aspects of the dying process. So it helped get me back into giving talks and workshops and finishing up my book.

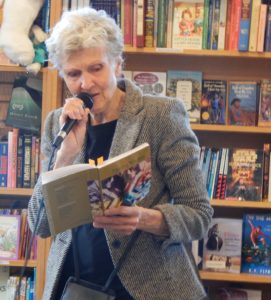

Cassandra chats with the public about death.

Ellary: What’s your book about?

Cassandra: It’s a little handbook that talks about very specific things regarding how to be with dying people. Tell them they’re loved and dear, maybe even get into bed and hold them; sing songs; read poetry. You know, I didn’t mention one important thing regarding how I transitioned into working with dying people, before Mother Theresa. Would you like me to tell you?

Ellary: Please!

Cassandra: I’d just gotten divorced from my second husband and I was on my way to Tahiti. I was on the plane going over the ocean. Everyone on the plane was asleep and I was looking out the window. And I said to God: “God, you give me a mission. I’m not a very good nurse. My daughter doesn’t think I’m much of a mother. I’ve been divorced twice. (Remember, I didn’t know I was gay at the time.) Give me a mission here so when I come home you’ll say, ‘Job well done, Cassandra.’”

Within two months I was doing private duty nursing for people dying at home. Carlene, who was dying of cancer, said to me, “When it gets close, will you be there to talk me through it?” So when she was dying and unresponsive, I told her, “This is it, Carlene. I’m going to talk you through it.” Her husband and her daughter gathered around. We put on some music, and when the cassette snapped off within the hour, she had died. We just told her how loved she was. She had abandoned her son when he was really young, and I told her, “You know, Carlene, you’re forgiven. You just did a good job living your life.” At one point she even gave a tiny smile.

When she died I went into the other room to let the family be with the body, and I thought, “My gosh! This is the answer to what I asked God for. This is my mission. I do it well; I love doing it, and this is what families need. They need this.” Now, of course, there are a lot of people doing this kind of thing, who act as death midwives. I think we need midwives to help families. To tell them things like, “Yes, you can touch, just be gentle. Yes, you can talk with them, just be gentle.”

Ellary: When you were talking Carlene through her dying process, you told her that she was forgiven and you told her that she was loved. Is there anything else that you really try to convey when you’re talking someone through the dying process?

Cassandra: Yes. For her, I put on a tape of some chanting that meant a lot to her spiritually (you know, it was the 70s) and put the tape by her ear. And I told her, “You’re safe and you’re loved. You did a good job living your life.” I said a lot of words over and over. Her daughter held her hand and touched her hair, and her husband touched her feet. Usually, I try to involve the family more. But in this case, Carlene had specifically asked me to talk her through it, so I focused on doing that. Do you want to hear another story?

Ellary: I’d love to hear it.

Ellary: I’d love to hear it.

Cassandra: One of our Project Nightlight volunteers was straight. Usually, our volunteers were parents or sisters of AIDS patients, or they were gay. This volunteer was straight and he’d been called down to Harbor UCLA Hospital to see a patient. He was walking down the hall and before he got to the patient, he heard a voice calling, “Dad! Where are you, Dad?” So he thought he’d go into the room. I’d taught the volunteers to go in really slowly and delicately and get in touch with what feels right. And he felt that it was right to go in.

He said to the patient, “I’m here.” The young man was so close to dying that he just said, “Oh Dad, oh Dad.” Andrew just talked to him as if he was this young man’s father, saying things like, “I’m sorry I couldn’t have been a better dad, I love you.” The nurse came in and just nodded. It was clear Andrew wasn’t this patients’ dad, because he was too young. And then the young man died. Andrew said he was so glad the nurse came in to see what he was seeing and validate that it seemed like the right thing to do.

I’ll tell you one more story if you’d like.

Ellary: Please!

Cassandra: There was one volunteer named Harley that called me up and said, “Cassandra, my dad’s dying. He called me from the VA up in Oregon. He was a terrible drunk and he abused and abandoned all of us, and I don’t know what to do.” So we talked about some of the things he had learned, and he went up there.

But he couldn’t say “I love you.” He just couldn’t. So what he did was help the nurse care for his father. He helped bathe and turn him, helped make the bed, and just stayed with him. So here’s this guy whose kidneys had totally shut down. And what happened? He survived. He came out of it. Harley had come back to LA, and got a phone call from the doctors saying, “We don’t know what happened, but your father’s recovering.” I think he recovered just enough to go back to the streets and start drinking again. But regardless, it just shows the power of being there with so much love. And that you don’t have to say anything you don’t feel.

Ellary: Thank you SO much for sharing these stories with me. I want to ask you, is there anyone in your life that you’d want to have talk you through your own dying process?

Cassandra: I’ve thought about that. I think we’re all so different, and we’re also different than we think we’re going to be. I will say that when I’ve had procedures, like a colonoscopy I had without anesthesia, it helped me so much when that nurse held my hand. So I imagined it would be the same, that it wouldn’t make too much difference who specifically was there. And then some people, they need to die without being touched and without being spoken to. Quietly, like they’re going to sleep.

Ellary: Cassandra, thank you so much for speaking with SevenPonds. It was really an honor to hear your stories.

What Was the Role of Project Nightlight During the AIDS Crisis And What Can We Learn From the Founder?

What Was the Role of Project Nightlight During the AIDS Crisis And What Can We Learn From the Founder?

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull