Yayoi Kusama

Credit:smithsonianmag.com

Born in Matsumoto, Japan in 1929, Yayoi Kusama is an internationally recognized avant-garde artist whose work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, including shows at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford England, The Center for International Contemporary Arts in New York, and, more recently, Tate Modern, London and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Kusama moved to the United States in the early 1950s and became an integral part of the postwar New York art scene. Her oeuvre spans a wide variety of art forms, including paintings, sculpture, performance art, room-sized presentations, films, fashion and literary works.

In 1965, the now 80-year-old Kusama began creating installations she called “Infinity Mirror Rooms,” which borrowed from her earlier themes of repetition and accumulation, transforming them into a participatory experience between the viewer and the work. Her first Infinity Room, “Phalli’s Field,” — a mirrored room strewn with handmade, pink-spotted phalluses — appeared in an exhibition titled “Floor Show” at the Castellane Gallery in New York in 1965. Since then, she has created no fewer than 20 distinct Infinity Rooms, each of which reveals another dimension of her expansive views on life, death and the afterlife.

In 2016, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington D.C., organized a traveling exhibition of Kasuma’s work, including six of her most critically acclaimed and well-received Infinity Rooms. Among them were two that spoke eloquently of the artist’s relationship with death and its aftermath: “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity” and “Love Forever.”

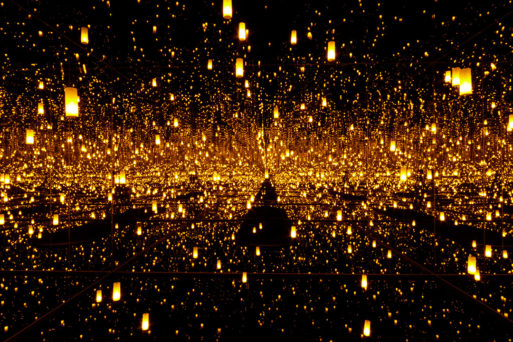

“Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity” (2009)

Credit: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore via artspace.com

The first of these, “Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity” is marked by a series of low-hanging Japanese lanterns, reflected in infinite variety on the room’s mirrored walls, ceiling and floor. The lanterns dance on every surface, alternating in intensity — sometimes bright, sometimes dim, sometimes leaving the viewer in total darkness so they cannot see their reflection at all. The text accompanying the installation explains, “For Kusama, obliteration is a reflection on the experience of death and the potential of the afterlife.” According to Artspace, it was inspired by the Japanese ceremony known as “toro nagashi” (flowing lanterns), a five-decades-old tradition in which participants float glowing lanterns down a river to commemorate the dead.

The second installation, “Love Forever,” differs from most of Kusama’s Infinity Rooms in that the viewer can’t enter the space but must look through two peepholes to see the flickering lights within. The lights are arranged in specific geometric patterns that Kusama conceived as a “machine for animation.” The piece dates back to 1966, at which time the title represented the spirit of the 60s — the civil rights movement, sexual freedom and opposition to the war in Vietnam. Today, the piece might also be construed as a statement about the eternal and everchanging nature of love.

“Love Forever” (1966/1994)

Credit: Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore via artspace.com

Although Yayomi Kusama is now in her eighth decade, she remains a vibrant and sustaining force in the international art world. As recently as 2017, she collaborated with the Hirshhorn Museum to make her Infinity Rooms accessible to people with mobility issues by providing disabled visitors with virtual reality headsets that allowed them to experience the rooms in their entirety. And in 2014, she completed work on a five-story building in Tokyo, which she later announced would be a museum dedicated solely to her own work. The museum opened on October 1, 2017.

Yayoi Kusama’s Captivating Infinity Rooms

Yayoi Kusama’s Captivating Infinity Rooms

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”