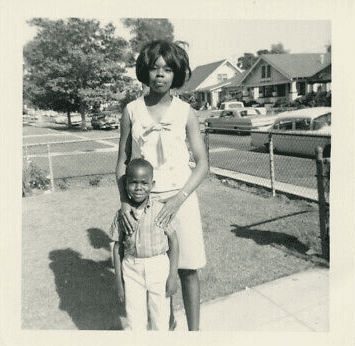

The family reunion in New Jersey when I became aware of my mom’s sudden aging

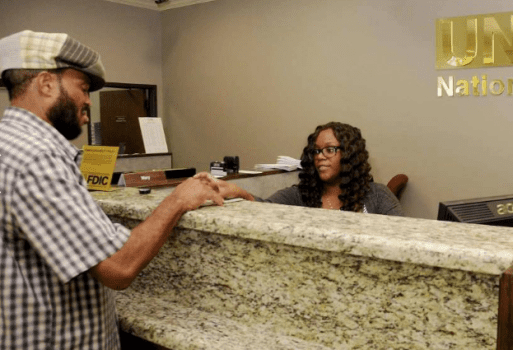

Credit: bfww.weebly.com

This is the story of Maurice and his mother as told to Jeanette Summers. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this story, Maurice talks about his mother’s death and the ways in which he cared for and supported her. He also discusses how he disagreed with many of the caregiving decisions his brothers made as she was dying of dementia and old age.

My mother died of a myriad of complications associated with old age. It unexpectedly brought out the worst in my three brothers.

When I travelled from California back to New Jersey for a family reunion, my mother — who was in her 80s at the time — wasn’t entirely herself. I hadn’t seen her for a few years prior to the reunion, and it seemed as if she’d aged in fast-forward. The mother I knew, who prided herself on her independence, who’d hike and go on 10-mile bike rides, had disappeared. In her place stood a fragile, elderly woman whose hands were prone to shaking and was suddenly wobbly on her feet.

I’m significantly younger than my mother’s three other sons. The brother closest to me in age is eight-and-a-half years older than I am. By the time I’d entered double-digits, all my brothers were out of the house. My parents divorced when I was in eighth grade so it was just me and mom for a very long time.

My mother was a woman made of unrelenting grit. Her father died when she was in high school, leaving 13 children in his wake; she was the second-oldest. She quit school, got a job, and played an important role in raising her younger siblings and keeping her household afloat. And so, it came as no surprise that — once my mother was without a husband — she knew exactly what she had to do and did it without protest or complaint. By the time I was 14, I was a true latch-key kid. My mother regularly worked double shifts, leaving prepped meal ingredients with cooking instructions in the fridge for me. Even though she wasn’t always as physically present as she would have liked to be, she’d help me with my homework whenever she was home. She’d take time off work to run the concession stand at my little league games or help out at my Boy Scout troop’s fundraising events. My mother actively showed me how much she loved and valued me every chance she got.

I never forgot everything my mother did for me. And so, when I saw — at that reunion — that she needed some assistance, I felt not only that I was obligated to be there, but also that I wanted to be there. I made the choice to go back to New Jersey and move in with her. I thought that I could do things like cut the grass and grocery shop for her. After all, her husband had passed away, and she was truly starting to seem her age. I figured she’d feel safer with a man around, that I could offer her a sense of steadiness and support. I had no idea that within three years, my mother would be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and that her health would degenerate to the point where I’d become her full-time caregiver.

One evening shortly I moved back, I brought half a cake home from work. “There’s cake in the kitchen, Mom,” I said. “I know that,” she said. “Jenny brought it to me.” Jenny had been my mother’s coworker over 25 years ago! This was the first time I noticed that something was seriously amiss with my mother’s memory and sense of reality. I made a doctor’s appointment for the next day, and the dominos began toppling from there.

At first, I thought that I was moving in to help out with daily chores and basic household upkeep. This ultimately turned into taking my mother to frequent doctor’s appointments, cooking for my mother, bathing and dressing her, all while enduring her combative episodes — an unfortunate side effect of Alzheimer’s. When my mother would snap at me and tell me she didn’t want my help, I’d suck it up and shake it off, knowing that I was doing the right thing — keeping faith that in some deep region of my mother’s heart, a steady, still place undisturbed by dementia — she appreciated everything.

My brothers — all of whom still lived in Jersey and wouldn’t have upended their lives to be present for our mother — wanted little to do with caregiving. I, on the other hand, was more than prepared to take on the responsibility. I worked as a vet tech — nurturing and nursing sick, hurt, vulnerable animals back to health — for years. Very little about the body — human or otherwise — shocks, scares, or repulses me. And so, when one of my brothers said, “How could you change and feed mom? Isn’t it disgusting?” All I said was, “She did it for us. How could we not do it for her?”

My oldest brother didn’t think for a minute about what he could do for my mother. Instead, he thought long and hard about what my mother’s bank account could do for him. He weaseled his way into becoming executor of my mother’s will. He drove my mother to the bank and had his name added to the signator’s card. He brought my mother to the doctor — the only time he ever did so — and had her deemed “incompetent” to make decisions for herself. When I confronted him and asked to see our mother’s bank statements, I was met with resistance and rage. “You don’t need to see them!” he screamed. I couldn’t believe his greed. But as angry as I was, I couldn’t squander too much energy on resentment. I had our mother to think about. All I wanted was for her to feel as healthy, comfortable, and secure as she could. Love was my only motive. Unlike my oldest brother, I didn’t want or expect anything in return.

As the years went by, my mother’s Alzheimer’s continued to progress, closing in on her mind bit by bit. Some days, she was herself; other days, she transformed into an aggressive woman who bore little resemblance to the one who raised me. Her body was also failing; she’d turned so arthritic that I had to put balled-up wash clothes in her hands so her fingers didn’t curl into spirals. Eventually, my mother became completely bedridden. Hospice set up camp at our house and, as it turned out, stayed for four or five years. The nurses joked that this was the longest anyone on Earth had ever been in hospice — that my mother was the toughest old woman on the planet. They weren’t wrong. But I did disagree with one thing the nurses said: that Alzheimer’s — compared to more gruesome and arguably more debilitating diseases — was a dignified way of passing. My mother’s heart beat persistently on, but I could sense her spirit waning — getting small and weak. Her faculties were slipping more by the day, she couldn’t get up out of bed, and — over the course of the past decade and change — all of her friends had been buried. What was dignified about that?

I’d frequently go into my mother’s room to check on her. One day, my mother looked up at me — a heartbreaking feebleness welling in her eyes — and said, “Call the doctor. I’m ready for the needle now.” My mother couldn’t stand what was happening to her, and just wanted it to be over.

Another time, though, my mother looked up at me and, in a moment of clarity, said something I’ll never forget: “Thank you. I didn’t want to die alone in my house.” I was certain, in that moment, that the sacrifice I’d made to move back to New Jersey was worth it.

The night my mother died was a night much like any other. I went to check on her in the middle of the night, as usual; she was lying, face-up, with a serene, almost angelic expression on her face. I’d never seen my mother look so tranquil in my life. I felt for her pulse; her skin was still warm, but there was no movement or sign of life underneath it. She was gone.

My mother was 94-years-old at this point. I was relieved for her; she finally got what she wanted. She was at peace. And she was absolutely ready. I was as ready as I could have been, too. My mother and I didn’t exchange any sort of formal, special goodbye, but in truth, we didn’t need to. My mother’s process of letting go of life — and my process of letting go of my mother — was gradual. Step-by-step, piece by piece, we’d been saying goodbye every day for years. When her final moment arrived, the sorrow I felt had nothing to do with guilt, remorse, or regret (I truly felt that I’d done everything I could for her). It had everything to do with love. My mother — my friend — was gone. She knew I loved her, and it was no doubt her time, but that wouldn’t change the fact that she would be so very deeply missed.

My Mother’s Death Brought Out the Best in Me

My Mother’s Death Brought Out the Best in Me

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead