“Words Aren’t Cheap” by Tory Dent (1958-2005) is a memorial that knows it cannot be a monument. It is a partial, sketched outline rather than a total portrait of a loved one who has died. Indeed, this acknowledgement of contradiction is precisely what allows it to be such an honest portrayal of grief.

“Words Aren’t Cheap” by Tory Dent (1958-2005) is a memorial that knows it cannot be a monument. It is a partial, sketched outline rather than a total portrait of a loved one who has died. Indeed, this acknowledgement of contradiction is precisely what allows it to be such an honest portrayal of grief.

Diagnosed with HIV at the age of 30, Dent was lauded for her unflinching accounts of the embodied realities of living with a fatal illness. Yet in “Words Aren’t Cheap,” the opening poem of the collection “What Silence Equals,” Dent grapples not with her own mortality, but with the loss of her friend Richard Horn.

The poem begins in a zone of uncertainty:

Into an aptless metaphor for this,

into its conceivable, metastasized equivalent

The first word, “into,” ushers the reader from an unstated starting point towards an equally unstable destination: metaphor. A metaphor for what? For “this,” the most ambiguous of pronouns. It is conceivable that “this” is death — the poem, after all, is written in memoriam — but the final word of the first line is left open, vibrating with possibility. What’s more, the metaphor into which the reader has been led, despite the device’s potential for illustration, is “aptless,” ill-fitting, unsuitable. It seems that by becoming “conceivable” and serving as an “equivalent” the metaphor has fallen short of “this.” (Isn’t death bound to exceed its descriptions?) Through these opening lines, Dent seems to be gesturing towards the limitations of her own project, highlighting the inevitably qualified nature of the poem to come.

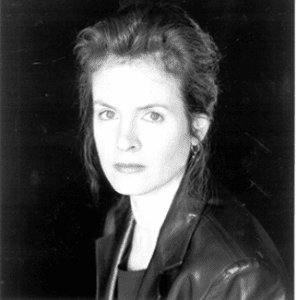

Tory Dent

Credit: Arne Svenson via poets.org

From this expansive opening, Dent zooms into concrete terms:

You’re dead and you died at thirty-four.

This sudden declarative tone is at once startling and stabilizing in its clarity. But it seems difficult for Dent to remain in this grounded state. As the poem continues, she looks not at her friend but at his absence:

So left without recourse, stupefied, we stare

at the sidewalk where the timbered body fell,

the chalked silhouette veined into the pavement,

unstable as a fresco as it is.

Here, indeterminacy (“chalked silhouette,” “unstable”) is in tension with palpable materiality (“timbered body,” “veined into the pavement”). Isn’t this a central tension while grieving? On the one hand, there is the painful, deeply felt reality of loss. On the other hand, there is the inconceivability of death itself. Strung between these poles, it is not surprising that one might be left “stupefied.”

Within this confused state, Dent acknowledges the ways in which mourning can transform our memories of those who have died, at times flattening or idealizing our loved ones:

“What Silence Equals”

references the famous

slogan “Silence = Death”

coined by AIDS activist

group ACT UP

Although it should, it doesn’t matter what you died of,

your sickness made sublime (much too) by our contracting lives,

by our ornery fear,

by our love suddenly experienced

with ludicrous unconditionality now that you’re gone,

so that we love instead as representative of you

the entire loaf of sky

…

because we regard it, however conciliatorily,

in the way and not in the way

you did.

Despite all the ways in which memory romantically obscures the past, these final lines allow the ways we get it wrong to coexist with the ways we get it right – we experience the world “in the way and not in the way” that our loved ones did.

This poem cannot communicate Richard Horn’s life to strangers, nor can it express the entirety of Dent’s grief. And yet, as the title reminds us, words aren’t cheap. There is value in acts of remembrance, even when they are inevitably imperfect.

“Words Aren’t Cheap” by Tory Dent

“Words Aren’t Cheap” by Tory Dent

Coping With Election Grief

Coping With Election Grief

Octogenarian Author Jane Seskin Offers a Model for Aging and Living Well

Octogenarian Author Jane Seskin Offers a Model for Aging and Living Well