https://archive.org/details/78_danny-boy-londonderry-air_glenn-miller-and-his-orch.-fred-e.-weatherly-j.-c-macgr_gbia0012081b

Oh Danny Boy,

The pipes, the pipes are calling

From glen to glen, and down the mountain side.

The summer’s gone, and all the roses falling,

It’s you, it’s you must go and I must bide.

So begins the infamous Irish ballad “Danny Boy,” a song that has long been a staple at Irish Catholic funerals, wakes and memorial services around the world.

The lyrics of “Danny Boy” have a certain ambiguity, lending themselves to function as a universal lament about separation, the finality of death, and the greater power of love. The lyrics neither specify the relationship of the singer to Danny Boy or the reason for Danny’s departure.

“Danny Boy” is not a completely original song. The melody comes from an Irish air called “Londonderry Air,” named for the County Londonderry where it was first collected. In George Petrie’s “Ancient Airs of Ireland,” where the ballad first appeared in print, Dr. Petrie credited a Miss Jane Ross of County Derry (also known as County Londonderry), Ireland, for notating “Londonderry Air” after hearing it played by an unnamed blind fiddler.

Mystery surrounds the origins of the melody. Legend has it that the tune was composed by a Celtic harpist named Rory Dall O’Cahan, who lived in Scotland in the late 17th century. Rory Dall O’Cahan may or may not existed, but he’s an important part of the fabric of the story of “Danny Boy.”

Credit: Ebay.com

And as it turns out, the famed lyrics weren’t written by an Irishman. They were penned in 1913 by a British lawyer named Frederic Weatherly. Before he began practicing law, Weatherly had been quite prolific as a songwriter, publishing about 1,500 songs in his lifetime. Weatherly’s sister-in-law, Mary Weatherly, was an Irish immigrant who sailed to America with Frederic’s brother in search of silver. On a trip back to England in 1912, Mary introduced Fred to “Londonderry Air.” Fred fused his heavy-hearted lyrics with the ancient melody.

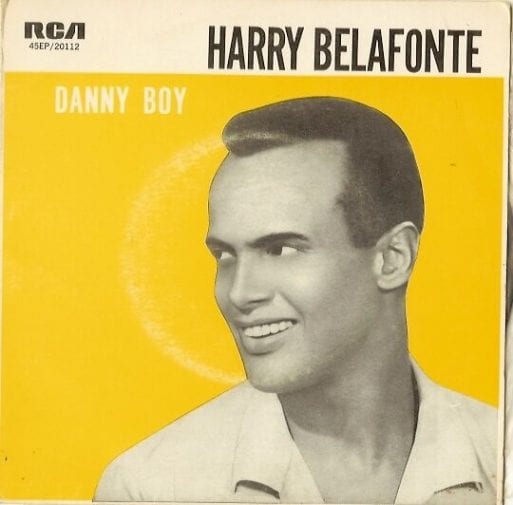

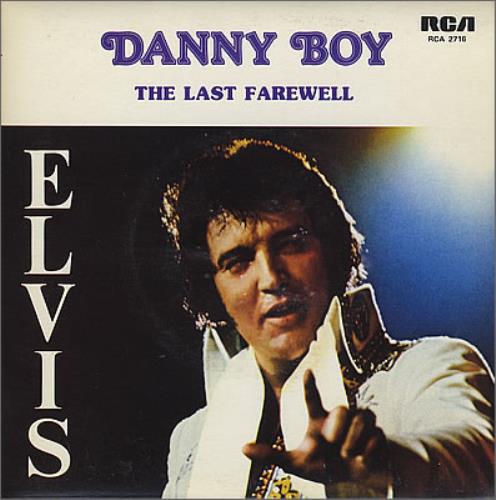

Weatherly gave the song to the English opera singer Elsie Griffin, who introduced it to a wider audience. The first recording was made in 1915 by the German vocalist Ernestine Schumann-Heink. Since then, “Danny Boy” has been recorded by artists from nearly every genre of popular music: Everyone from Elvis Presley to Bing Crosby to Kate Smith to The Pogues to Harry Belafonte to Johnny Cash has their version.

John F. Kennedy, New York Fire Chief Peter Ganci (who was killed in the World Trade Center attack), Princess Diana and Elvis were all laid to rest to the haunting strains of “Danny Boy.” In 2018, as per the late senator’s request, opera singer Renee Fleming sang a rendition of the tune at Washington National Cathedral during the memorial service honoring John McCain. For the senator, requesting the song at his memorial service was a return to his Scot-Irish roots.

Credit: Irishpost.com

In 2007, the Roman Catholic Church raised the ire of Irish Americans when it banned “Danny Boy” and all secular music from Roman Catholic funerals in the United States. Rev. Bernard A. Healey said on the subject:

“Part of what I do at a funeral Mass is try to lift people’s spirits. But the song is emotionally manipulative. Everything I’ve spent the last hour working toward is gone within two minutes because everyone is reduced to tears.”

Irish Americans did not take kindly to the news. “Danny Boy” has long been cherished by police officers and firefighters who identify with its message, which tells the story of a young man called to military duty by the sound of distant bagpipes and a loved one who promises to wait for him. Fire and police departments in New York, for example, have historically been dominated by Irish Americans, and “Danny Boy” is often blown on the bagpipes during ceremonies for fallen officers.

In response to the Church’s decision, Irish Americans began writing letters to “Rhode Island Catholic,” formerly “The Providence Visitor.” The paper’s rebuttal said the editors talked to Irish priests, who said “Danny Boy” would never be allowed in churches in Ireland. The Church has not reversed its position, so Irish Catholics must choose how they wish to incorporate the song outside of church, if they so wish.

But if you come and all the flowers are dying,

If I am dead, as dead I well may be.

You’ll come and find the place where I am lying,

And kneel and say an “Ave” there for me.

“Danny Boy” by Frederic Weatherly (and Rory Dall O’Cahan)

“Danny Boy” by Frederic Weatherly (and Rory Dall O’Cahan)

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska