Credit: movingthrough.live

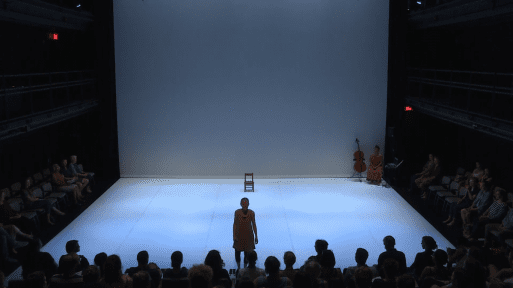

“They Are All,” a contemporary dance piece choreographed by Murielle Elizéon and Tommy Noonan, starts off with a single dancer facing the audience. In silence, she begins to walk backward toward a chair in the middle of the stage, her slowness both agonizing and hypnotic. Finally, she stands on top of the chair, then climbs down and sits; at last, with the same slowness, she eases herself onto the ground until her face meets the floor.

In this simple sequence, the most mundane actions are imbued with drama — a paradox that may be familiar to anyone who has lived with Parkinson’s disease. “They Are All” is an exploration of the limitations and possibilities posed by neurodegenerative disorders that affect balance and movement. The performance was commissioned by the American Dance Festival and marks the culmination of “Moving Through,” a series of dance workshops tailored to people with Parkinson’s disease. The workshops were led by Elizéon and Noonan in collaboration with other choreographers and teachers, as well as physical therapists and neuroscientists.

Credit: Sarah Marguier via movingthrough.live

While Parkinson’s disease manifests uniquely for everyone who has it, the disease typically affects motor control and balance, which would seem to preclude activities like dance. However, multiple studies have shown that regular dance classes can significantly improve motor and cognitive functions for those suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Dance for PD, founded in Brooklyn in 2001, now has affiliates in 25 countries and currently offers classes online due to COVID-19.

Scientists have yet to fully understand why dance is beneficial for people with Parkinson’s disease, but the answer may lie in the music. “External auditory cueing provides a template of when to move,” Dawn Rose, Senior Research Associate at Lucerne University of Applied Sciences & Arts in Switzerland, told Forbes. Responding physically to cues can be helpful for restoring motor control. Christina Soriano, founder and executive director of IMPROVment, emphasized the importance of honing those responses to be immediate and instinctive: “That quickness, that rapid pace, helps us practice change – and, to take it even one level a little deeper, we’re practicing being human beings,” she said in a video on the company’s website.

Everyday tasks can be challenging for those with Parkinson’s disease. Because the disease affects balance, falling can be a major risk. For this reason, Elizéon and Noonan’s workshops focus heavily on “floor work” — learning how to move on and off the floor safely, coming to see it as a “potential partner rather than a potential threat.” The classes also focus on walking, seated mindful movement and individualized “body stories.”

Credit: Sarah Marguier via movingthrough.live

Outside of physical benefits, dance classes can also offer those with Parkinson’s disease — and those without it — a sense of community, belonging and self-efficacy. These psychological improvements are no less impactful, especially for anyone experiencing symptoms like mood changes, depression or fatigue.

“They Are All,” which was performed at the Culture Mill in Saxapahaw, North Carolina, and can be viewed in its entirety on the Moving Through website, features dancers of all ages moving in a variety of ways — some fluid, some jagged, some natural, some forced, some casual, some choreographed. As a practice, dance can help us understand and improve symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. As a performance, it does something perhaps equally powerful — it lets those living with the disease share their experience through a profound and universal medium.

“Moving Through” Project Explores Parkinson’s Disease Through Dance

“Moving Through” Project Explores Parkinson’s Disease Through Dance

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?