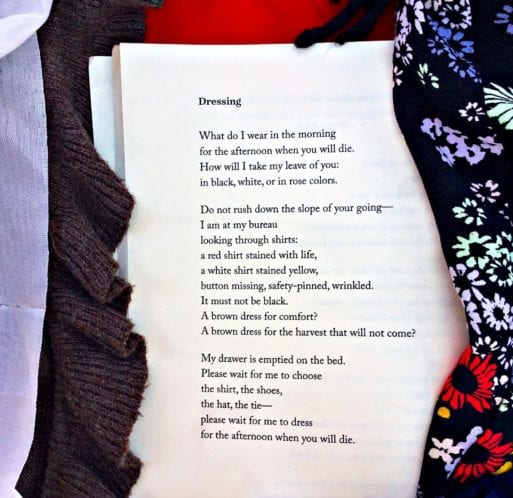

We all have wounds we press harder to ease the ache. Again and again in her plays, essays, and poems, Sarah Ruhl celebrates the life of her father and grieves his death from cancer in 1994. In her book “44 Poems for You,” Ruhl talks both about her father and to him. The poem “Dressing” directly addresses a you, Pat Ruhl, who doesn’t appear on the page and instead waits in an unseen hospital bed or in hospice care. The I is Sarah herself, Pat’s younger daughter, who’s in her bedroom getting dressed — or trying to — before returning to where her father waits in his last hours of dying.

In the afterword of “44 Poems,” Ruhl talks about direct address and the role she wanted it to play in her poems: “[A] you in the poem automatically opens itself to the reader. I wanted to open them to you.” Nearly all the book’s poems sit in a relationship between an I and a you, intimate and sometimes private. But Ruhl also gives the reader (us, you and me) “permission to peer in, to take part in the relation.”

“Dressing” sits in a moment when a daughter has stepped away from her father one last time while he’s still here to be away from. If we’ve done this with someone we love, we know this moment. The emergency is as exhausted as we are, and we’ve stepped out of the hospice facility or the living room with the hospital bed, just for a moment, to take a breath or take a shower. It’s been going on for such a long time, and we’re as emptied as Sarah’s bureau drawer. But now, suddenly, it’s the end, and the emergency finds within itself a terrific, terrible strength for a little more, and we do too. We return to our beloved. When we’re absolutely emptied and have nothing left, love is what’s left. Love is the last thing, the only thing left to give. Love is the emergency of our lives.

Ruhl opens this poem to us, to me. This is what I see when I peer into this poem: Sarah’s emptied bureau drawers look more like a grave than a hole dug in the cemetery. I see my own drawer that held what I liked and needed, wanted and used. I know what belongs there. It had everything I knew in it, even the junk, crumbs, and trash. But I’ve never seen that hole in the ground before.

… I just paused writing these words you’re reading and called my father.

Back in the poem’s bedroom, the I who’s Sarah looks through her clothes, shirts and dresses, knowing she’s choosing what to show herself and everyone around her: “a red shirt stained with life?” “A brown dress for comfort?” All she knows is “It must not be black.”

For all the certainty of the day, this question has surprised her: “How will I take my leave of you?” This decision wasn’t on the hospice checklist. There’s no plan for this part. For Sarah, for Pat, that most awful question has been answered for a long time: How will you die, you whom I love best, most? We spend our lives wondering that, while also wondering whether maybe we’ll die first, the luckiest unlucky. Sometimes we don’t know the answer to that most awful question until after it happens — the car wreck, the secret suicide — and we’re at the funeral with our minds blown. But other times, like in this poem, everyone has been waiting for today.

There’s been so much waiting, an agony of waiting, and even then, Sarah asks her father for more waiting: “Please wait for me […] please wait for me.” If we’ve done this with someone we love, we’ve said that too. She asks for just a little more time, because she wants to choose her clothes as best she can — and because as soon as she chooses, she has to return to him and lose him.

After so many awful, necessary end-of-life decisions, now this one — also awful, for all its lightness.

“Dressing” by Sarah Ruhl

“Dressing” by Sarah Ruhl

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying