Mediator and conflict resolution specialist Kimberly Best has a heart trained in peace and peacemaking, including resolving conflict at the end of life.

Those two things have been at the center of a lifetime of service, spanning a career that has taken her from hospital emergency rooms to conflicts between partners and loved ones to those seeking wisdom and comfort in their final days.

Owner of mediation practice Best Conflict Solutions and author of the 2019 book “How to Live Forever: A Guide to Writing the Final Chapter of Your Life Story,” Best started out as a registered nurse who learned working in intensive care and trauma units that no one is promised tomorrow.

“I developed an almost compulsion about our need to live well in the moments we have,” Best recalls of her experience. “And part of that living well is, indeed, how we treat each other.”

Having raised five children — one of whom graduated from West Point and recently returned from Afghanistan, and another who is a political activist — Best is no stranger to bridging worldviews that often question and challenge one another.

Her interest in human relationships and behaviors led her to attend graduate school at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and earn her master’s degree in conflict management from Nashville’s Lipscomb University.

Best works with Mediators Beyond Borders International, an organization that promotes mediation worldwide by helping those affected by conflict build peacemaking skills. She focuses her time on the group’s Democracy, Politics, and Conflict Engagement initiative, which helps leaders of American social change movements engage with conflict constructively to strengthen democracy and promote justice.

Whether it’s in the home or across international borders, Best believes true conflict resolution begins with the simple act of grace — toward others and, most importantly, toward oneself.

“In conflict resolution, the most difficult person in the room is the one in the mirror,” she says. “It’s hard to admit, but it’s true.”

A mother and grandmother of four, Best lives in Franklin, Tennessee, where she runs her practice.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Before we discuss resolving conflict at the end of life, what exactly is conflict? Where does it come from, and what is its function?

We think of conflict as another person’s being a problem, but it is a biological reaction, a survival mechanism. Our brains are wired in such a way that everything we see in the present is compared to the past. Very often, our brains are working quickly to determine: Are we familiar with this, have we been here before? It doesn’t care if it’s right or not — it’s just looking to categorize and file away an experience. I tell people our first reaction, especially in conflict, is coming from our unevolved hindbrain, which is governed by impulses to hide, fight or freeze. What we want to do instead is use our thinking brain, which is a response brain.

We can evolve and train ourselves to recognize when we’re being reactive and, hopefully, not respond in a way that is intentionally hurtful. But the biggest thing is to come back and move through the conflict that can build up in a relationship. If we don’t, it’s like having a trash pile — we build up these negative memories, this animosity — and that’s when people can look at that trash pile and eventually think, we just don’t have enough to connect.

I encourage people to see conflict not as a wall but a door. Moving through that door is difficult, mostly because we haven’t learned how to do it. It gets easier, though, as we practice and learn.

Kimberly Best with her family near her home in Franklin, Tennessee

Conflict is as old as time itself. But where do things stand now, given today’s political climate and social media’s laser focus on the divisions between groups and ideologies?

It’s actually a little scary right now, because the conflicts are so big and people are so polarized right now that getting anyone to be willing to listen, let alone even have the discussions, can be difficult. I might post an article on social media, and it will be on something like peace or listening or reaching out. And sometimes, it’s almost like I’ve posted something controversial. People won’t touch things around even peace. It is very difficult when something like peace is politicized. When our virtues are politicized it gets a little bit tricky. I think right now a lot of people are reluctant to engage in conversations that could actually bring another side that’s believable.

How might we shift our thinking, or our fears, around conflict resolution?

One problem is we have developed a culture right now where mistakes are not tolerated. We’re so busy pointing out a mistake, no matter how small it is, and then we label the person as the mistake. We have now made people into their worst moments. And we’re all bigger and more than that.

When I’m working with people, I ask them, “What if you’re wrong? What’s the worst thing that could happen?” The worst thing that can happen is that we learn something. Or we might have to apologize. But it’s not the gut feeling that we have that if we’re wrong, then we’re not worthy as a person. We have to start giving ourselves grace to be wrong and give the same grace to other people. Sometimes, we have to let people off the hook for what they’ve said. We also need to know that when we react, rather than respond, it’s coming from a place of our own hurt. And we all do it.

What’s your advice for people facing end-of-life issues? How can people sort through long-held feelings and problems when there may be little time left to do so?

A lot of studies have been performed that ask people what matters at the end of one’s life. And a high percentage of people say it’s not what you did for a living, that it’s relationships that matter. We know that going in, but then may get busy with our jobs and the things we think are important. And sooner or later, if we live long enough, we tend to recognize these things may not be bringing us the fulfillment that we thought they would.

The first thing I would say is that it’s never too late to resolve conflict at the end of life. We are always writing our stories. And we have the power, not to influence what people will do in that story but who we are going to be in that story. So, what is your truth that you need to say to someone? It would help to say, “I recognize this about our relationship,” or, “This is what I wish we had, looking back, and this is what I would like to see moving forward.” It’s about speaking honestly and being vulnerable.

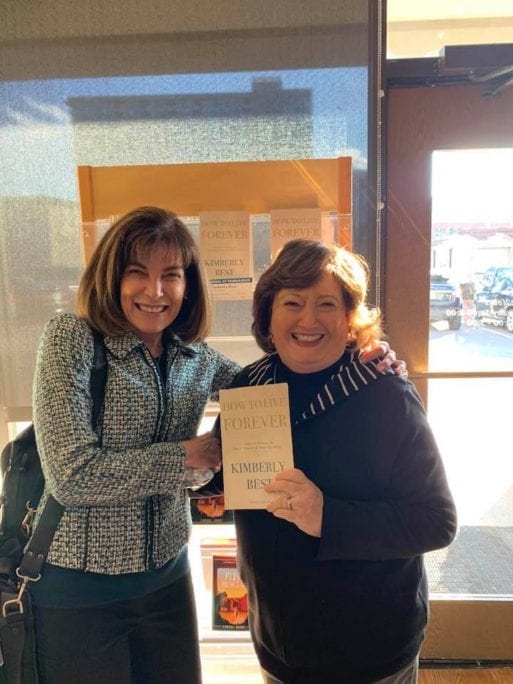

Kimberly Best, left, at a February 8th book signing at Parnassus Books in Nashville

One important dynamic for conflict resolution at the end of life is mitigating regret. I have found I tend to regret things I haven’t done — not what I’ve tried to do and failed at, not what I did that hasn’t worked out. I’ve also found with people that the thing they regret is the unspoken, the unsaid, the undone.

So, take a stab at it, but let go of the outcome, let go of what you expect the right outcome to be. Gift your truth to someone else and maybe trust that, in your sincerity and your honesty and in your vulnerability, there will be the beginning of a transformation.

What role does forgiveness play in conflict resolution?

Forgiveness as a “one and done” is a myth, almost like grief. It is a process — we forgive, and we need to forgive again and again. It’s important to recognize that the path to forgiveness starts with self-forgiveness. We need to forgive ourselves for not being perfect and forgive ourselves for being hurt, whether it was intentional or unintentional. It’s helpful to think that people are doing the best they can, in the moment they have with the tools they have.

Life is hard and it’s full of injustice and it’s not fair. We get so indignant because life’s not fair, but who ever said it was supposed to be? So how do we move on, given that life’s not fair, given that we do hurt each other, all of us hurt each other? We need to recognize that bad things happen in this thing called life and let go of the hope or the expectation that they’re not supposed to. It also helps to see the humanity in the other person. They say “hurt people hurt people.” That’s really an oversimplification, but it’s true.

Is the threat of, or experiences with, COVID-19 making it harder or easier for people to have the difficult conversations necessary for conflict resolution?

I was hoping the virus would afford people the opportunity to start having conversations around death and dying. But what I have found for the most part is still denial. I think as Americans, we’re fighters. There’s a problem and we’re going to fix it, or we’re going to find the solution. But sometimes the solution is accepting parts of the problem.

Kimberly Best excited about her

book “How to Live Forever: A Guide

to Writing the Final Chapter of Your

Life Story,”

For some couples and families who have already had fractures, the virus has created more fractures for them. From my perspective, it seems we are a bit of a disposable society. If something doesn’t fit or work anymore, we throw it away and get something else. I feel like we’re doing that more and more with relationships. And the cost to us as a society is staggering. So much more than putting our work into healing things, we’re putting our work into fighting things.

[With COVID-19] there also can be a denial — we’re tired of the virus and, therefore, it doesn’t exist — but if we deny what the problem is, then we’ll deny what potential solutions are. While I expected the pandemic to open our willingness to discuss death, I have not seen much movement at all. Maybe it’s still too early.

Do you have any advice for people living in today’s especially difficult time?

A friend told me a long time ago that in life there are sorrows and there are joys. And the sorrows will find you, but you must look for the joys. The word that comes to my mind is “grace.” We need to give ourselves grace, to be kind to ourselves but to also be kind to each other — because we are all struggling. To be human is to struggle.

For myself, I have to remember to look for the joys, to look for the moments in which I can make something better for someone else. When I remind myself that all I have is now, and that I can make this the best now possible, that has kind of been the hold for me when I’m really feeling stuck.

Resolving Conflict at the End of Life Can Bring Peace and Grace

Resolving Conflict at the End of Life Can Bring Peace and Grace

Are “Rage Rooms” a Healthy Outlet for Grief and Burnout?

Are “Rage Rooms” a Healthy Outlet for Grief and Burnout?