Mark Gilbert, Ph.D., associate professor of Medical Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Omaha Credit: Mark Gilbert

Mark Gilbert never thought of himself as a flattering portraitist.

“It takes a great deal of courage to sit for a portrait at the best of times. It wasn’t unusual for me to genuinely offend the people that I was working with,” he said.

After a decade working as an artist, Gilbert said he had his most difficult challenge when he was asked to draw patients receiving surgery for facial difference and head and neck cancer.

Normally neurotic and anxious behind the easel, Gilbert felt a new type of trepidation sink in at the prospect of creating portraits of people that could be far more vulnerable than his usual subjects.

“I had the notion of working with people that I assumed, rightly or wrongly, were going through one of the most traumatic moments of their lives.”

The project would soon be a driving force behind his work for the next 20 years as he worked to investigate the overlap and influence art and medicine could have on one another.

Gilbert grew up embedded in the arts as the son of Scottish artist Norman Gilbert and art teacher Pat Jordan. He graduated from the Glasgow School of Art, his father’s almost alma mater. Norman was described as “unteachable” by his professors and was dismissed from the GSA after three years. Gilbert honed his blunt style for 10 years, showing in galleries, teaching and generally enjoying the ability to live and eat while creating the art he wanted to. It was only through a chance meeting on a train in 1998 that he combined his passions with the field of medicine.

Gilbert had earlier made the acquaintance of Professor Iain Hutchinson, a head and neck surgeon at Royal Hospital in London, whose wife had commissioned several paintings from Gilbert, and the two got to know each other through the United Kingdom’s art scene. One day Gilbert was on the platform about to board a train to London from Glasgow when he ran into Dr. Hutchinson going the opposite direction. Dr. Hutchinson came with a proposition: Gilbert’s portraits could not only show the transformative possibilities of head and neck surgery but also provide a level of catharsis for the participants.

“I thought he was incredibly naïve,” said Gilbert, recalling his skepticism at the time. He had made his career on avoiding sentimentality. “I had to change dramatically how I viewed my relationship with the person I was sitting with.”

Gilbert agreed. While the original project was only slated to last six months, his shift in approach and the reception from patients allowed the project to blossom into a three-year-long portrait series, “Saving Faces.” The series debuted in 2002 with over 100 paintings. The exhibit then toured Europe, the UK, and the United States, and even showed in the National Portrait Gallery in London for three months.

Nearly two decades later, Gilbert’s work landed him at the University of Nebraska Omaha, where he teaches art and is a professor of Medical Humanities. He has authored peer-reviewed studies on the impact of art in a clinical setting with UNO and shown his work in museums and medical centers across the U.S. He also designed a Medical Humanities curriculum for his Ph.D. studies at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

I sat down with Gilbert to discuss the impact of his work and how art can provide meaning at the end of life, shape the experience and provide outlets for patients and caregivers. We also explored his own personal connection to how art can combat grief.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What sparked your interest in continuing to work with patients with life-threatening or life-limiting illnesses after “Saving Faces?”

I spent an inordinate amount of time with the people I was working with. They didn’t like looking in the mirror; they didn’t like looking at photographs, but they enjoyed looking at the painting, and some even got a sense of empowerment from it. I thought, “What was it about the painting or what was it about this community I was working with that made them respond so favorably, more favorably than the people I normally worked with?”

A portrait of an individual is not just a portrait of an individual. It is a portrait of an individual being looked at. It’s a record of a relationship. With the relationships I was so fortunate and privileged to have with the people I was working with … they allowed me to explore their experience with the drawings and paintings. They associated that resulting picture with that experience. Often [the experience] is incredibly powerful and positive to the people I’m working with.

Portraits of Care, The Bemis Center, Omaha, NE, 2008

It can also communicate the patients’ experience as well. It was another means of expression for them. Often the fancier the walls that the portrait was hanging on the more empowering it was for them.

How did you find yourself as a Glaswegian in Omaha, NE?

As a result of the exhibition coming over to universities, I would get invited to become a part of the seminars and the symposiums. When it came to Omaha, it was facilitated by the University of Nebraska Omaha and the College of Public Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.As a result of my week there and the success of not only the exhibition but the collaboration between the Medical Center and UNO, I was invited to come over and work on a project that was using the visual arts explicitly as a research method. I was working with patients and caregivers from across the spectrum, I was with people who were having babies and people in the last days of their life and their caregivers. Those portraits are actually hanging in the nursing school at the Medical Center.

What was the response from students or faculty to those portraits?

They did some before-and-after evaluations of the students’ attitudes toward the patients and their empathy toward them. It was shown to be beneficial in their learning to engage with patient narratives, a focus on reflection for them. I was able to address important aspects of the patient experience that weren’t reflected in the bio or their file.

What were the specific findings that either confirmed some assumptions or surprised you from the study in which those portraits were created?

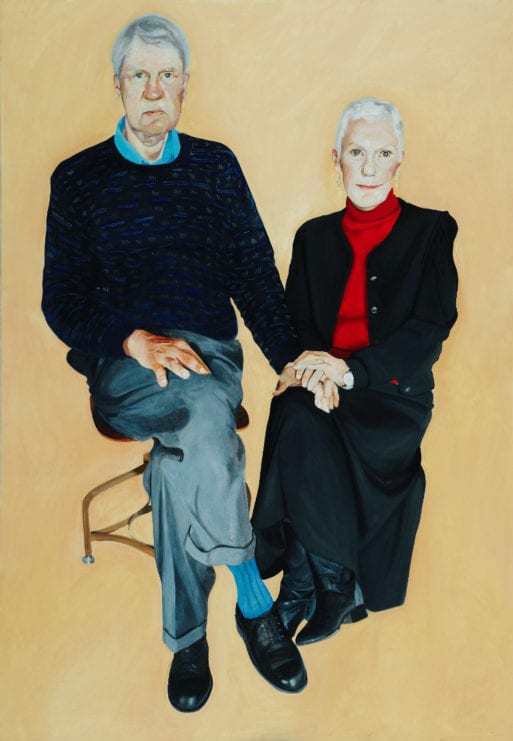

One of the findings was the notion of the relationship. It allowed us to look at the relationship between patient and caregiver a little bit more. We all recognized that the pictures showed that fluidity, that mutuality between patient and caregiver. But there’s only one painting in the whole collection that features the patient and caregiver on the same canvas. That was a gentleman named Rob, who was portrayed with his wife Marti. What I got to know because I spent a great deal of time with them was that Marti had her own health issues and was a cancer survivor. I was 35 at that point, and it hit me like a thunderbolt that we’re all going to have to be caregivers and patients in our lifetime, and I had not been either up until then. It was one of the most frightening realizations, but also strangely one of the most reassuring.

Robin and Mardi, Oil on Canvas, 2007, by Mark Gilbert

There was also how many of the participants engaged with and valued the experience. They relished the fact that pictures could testify to their experience. There was a woman Betsy, who had bariatric surgery and successfully lost weight, but still, her self-image hadn’t changed. Looking at her portrait, she not only started to see what everyone else had been seeing, but she also in her own words said, “I look beautiful, I’m beautiful.”

Your experience with portraiture at the end of life became very personal when your father began a series of drawings of your mother after she suffered a stroke and spent her final days in the hospital. Why do you think he responded that way, and what was your reaction to the drawings?

After the diagnosis [of dementia], my dad continued to draw and paint my mom as he had done for 70 years. Although when you look at those later pictures, the dementia isn’t explicit. But once you know the context, you not only have a record of an “artist and sitter” and “husband and wife” but a moving record of a patient and her partner in care.

She was unresponsive from the stroke in the final eight or nine days, and while my father kept vigil with her day and night, he began to execute this series of final drawings in the hospital.

I was still working in Canada in medical school at Dalhousie University. I was dumbfounded to know he was doing the drawings. I was kind of shocked, but not in a way that I thought he ought not to be doing it — I just never thought he’d do such a thing. I think we don’t often take in the concerns of the partner in care. If anyone thought it was unusual for my dad to do those drawings, they should understand people in that situation have to find a way of making sense and to express themselves.

For years when I would speak about my work, I always told anecdotes of people I had worked with. And I had this nagging doubt of, “Am I embellishing? Is this an authentic retelling of the story?” It wasn’t until I witnessed the drawings my dad did of my mom that I thought, “I get it now.” Now the most traumatic moment of my life was rendered in this form that allowed me to reflect on what was happening. Although I was shocked my dad did those drawings, I appreciated it straight away. He was making sense of what was happening.

Did you feel compelled to do the same with your father around the time of his death a year ago?

I often used to wonder if I would draw him. But I didn’t. I don’t think I had the guts. At that point, I understood what a courageous thing it was for him to do. But he did it because he had to. It was the only way he could make sense of it. It wasn’t, for him, unusual.

A pencil drawing by Norman Gilbert of his wife, Pat, as she was dying after a severe stroke.

Credit: Norman Gilbert

What can folks take away from exploring the visual arts and medicine, especially in the end-of-life experience?

My dad talked about how he could have watched the television, he could have read a book, he could have done anything. But he said by drawing it helped him forget about what was happening. He talked about when he was drawing her in the hospital: “I was drawing Pat again.” What was helping him forget was this paradox that he was engaging deeply with what was happening. He had the means to do [these drawings] because he knew how to draw. It made me ask, “Why isn’t there a pen and paper in these rooms, enabling people to draw or write, make poetry, or play knots and crosses? Just have something that’s not CNN.”

I think the arts can raise these paradoxes and address what makes us feel most vulnerable. The arts at the end of life are constantly used in memorials, whether on the memorial card or at the cemetery or at the service. The arts can play a huge part in comfort. But sometimes we underestimate how the arts can also challenge us in these moments. Through that challenge, the rewards are even more pronounced.

Finding Meaning at the End of Life Through Art

Finding Meaning at the End of Life Through Art

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

Thank you for a most enlightening interview. I was always aware of the power of portraits but Mr. Gilbert’s work displays the multifaceted understanding that a portrait can present. His paintings are a testament to mankind’s better angels.

Report this comment

Thanks you, Chris. Mark’s work is incredibly inspiring to all of us here at SevenPonds. He is truly a genius at what he does.

Report this comment