Mary Jane Mann and her daughter, Carol Kelly, with friends in Switzerland

Credit: Courtesy of Carol Kelly

Overheard in conversation, Mary Jane Mann’s story might be mistaken for that of an elderly victim of guardian abuse in the recent Netflix film, “I Care a Lot.” But for her, the story was all too real.

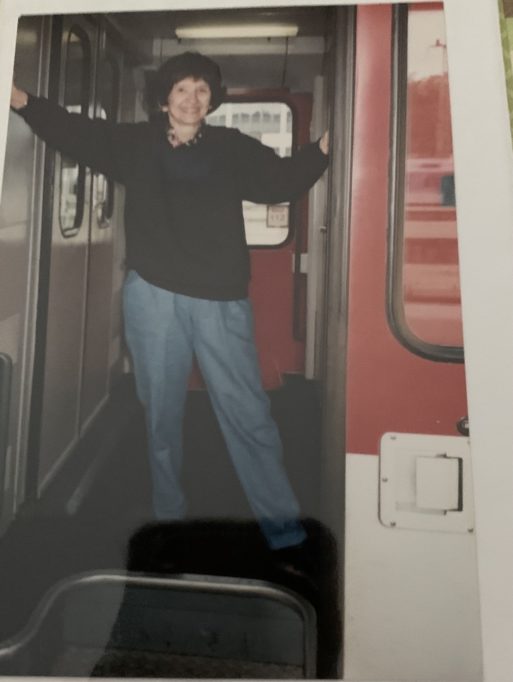

Mann was a vibrant, 85-year-old woman living independently in Sacramento, California, when a family disagreement — beginning when one of her daughters allegedly attempted to have Mann change her trust — resulted in someone making an anonymous call to Adult Protective Services. Not long after, a court placed Mann under conservatorship; she wasn’t even present at the hearing. Mann had been a lifelong volunteer and world traveler, and had served as executive director of the Orange County, California YWCA. She’d actively saved for retirement. Multiple doctors reported she was competent. Yet like a concerning number of elders under guardianship or conservatorship around the country, Mann found herself suffering at the hands of the very system designed to protect her.

Mann, who loved to travel, pictured riding a train in Europe

Credit: Courtesy of Carol Kelly

Suddenly, the conservator had her name on Mann’s bank account and trust, and was spending her money and receiving her mail. Mann’s driver’s license was taken away — though she eventually got it back. “I wake up crying at night,” Mann said of her situation in a 2011 CBS interview. “I just can’t believe this is happening.”

While there is little reliable data, a report that same year from the National Center for State Courts estimated some 1.5 million American adults to be under guardianship nationwide. Many times, guardians and conservators serve an important purpose: They make tough decisions and handle complex affairs for adults who are unable to do so for themselves, and who may otherwise become targets of fraud or be taken advantage of by family members.

But as a number of shocking reports from around the country — and the recent coverage of Britney Spears — has demonstrated, the system is easily abused. And when it is, victims struggle to obtain justice. While Mann — with the help of her daughter, Carol Kelly — was eventually able to prove her competence and get out from under conservatorship, her success was far from common. Mann died in 2012, and Kelly feels certain the situation took years off her mother’s life by escalating her blood pressure and causing panic attacks. Even after it was over, Kelly said, her mother was anxious it could happen again.

“They’re bullies, they’re predators,” Kelly said. “They’re still doing it and getting away with it. That’s what’s criminal.”

Who Are Guardians and Conservators?

In each U.S. state, adult guardians operate under different laws — and different terminology. In some, a guardian or conservator might be appointed for the person — making decisions such as where the ward will live, what medical procedures they need, and who can have contact with them. A separate guardian or conservator might be appointed for the person’s estate, handling financial matters such as paying bills, selling assets and balancing accounts. Sometimes, a guardian or conservator is appointed to just one of these roles, or the same guardian or conservator might be appointed to both. A guardian or conservator can be a family member, a private professional — paid from the individual’s estate — or a public guardian, who is funded by the state or local government when a ward does not have assets.

Pamela Teaster, a professor of human development and family science at Virginia Tech and director of the Virginia Tech Center for Gerontology, said that while there’s little to no official data on adult guardianships, the majority of guardians around the country are likely family members. Still, there is no guarantee that family guardians will act appropriately. There have been numerous accounts of family members stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from elders, pressuring them to sign over assets or engaging in other forms of abuse or neglect. Often, a court-appointed guardian or conservator is seen as a way to protect elders from unscrupulous family members, and to ensure that someone is acting in their best interests.

Yet this doesn’t always happen. Sometimes, professional conservators or guardians may even seek to create rifts among family members — especially those who are already in disagreement — in order to gain control over a ward and their assets. Once they’ve done so, they’re free to bill the ward’s estate for their time and legal fees, and to continue doing so until those elders’ homes have been sold, their accounts have been emptied and they’ve been confined to a nursing home — possibly with very limited access to family.

In Mann’s case, a California conservator — the subject of a chilling, year-long ABC10 investigation, which delved into Kelly’s story as well as that of others — filed a petition for temporary conservatorship of Mann, claiming that she “appears to be suffering from cognitive impairment and moderate to severe short term memory loss.” The petition also alleged that Kelly had been attempting to isolate her mother and gain control of her assets — charges Kelly said were flat-out lies. Kelly said that she had wanted to work things out with her sister, but that the conservator and attorney had actively prevented that from happening. “It is not in their interests to have families get along,” Kelly said. “They tear families apart.”

Pamela Teaster is one of the few academics studying professional guardianships and conservatorships.

Teaster said that ideally, paid guardians should be certified or licensed by some professional body, and should be appointed only when there’s no other choice. “Families get fractured, because either the guardian is justified in separating the family — because they just agitate and upset the person — or they really are preventing them from seeing how the older person is,” Teaster said. Of unscrupulous guardians, she said “there’s probably one in every state,” and that “there’s a pocket of corruption everywhere.” Yet more often, Teaster said, the issue is that private guardians and conservators have so many wards that they simply can’t provide them with the care and attention they require.

Teaster — who has herself acted as a guardian twice for wards who were not relatives, mostly to learn from the experience — said that it’s not an easy job. She said that the ideal relationship of guardian to ward would be 1:1, and that the highest she recommends for professional guardians is 1:20, the rate mandated in Virginia. Many states have higher caps — such as Florida, where it’s 1:40 — while others don’t have caps at all, leaving guardians and conservators with as many as 100 wards apiece. These wards all too often end up warehoused in nursing homes, neglected and forgotten. “The problem is that if you put a cap on it, you don’t have enough slots for people,” Teaster said. “But I still, 20 years later, would not lift that cap because when you do these problems begin to happen.”

Ideally, Teaster said, a reliable family member should be enlisted to care for an incompetent loved one. “When we do the right things, we preserve the remaining rights people have,” she said. “I have to believe it’s most of the time. But when [guardian abuse] does happen — a percentage of that — it’s terrible. And you might not even know about it because the person under guardianship has lost the rights they have.”

How Guardians and Conservators Abuse Elderly Wards

What makes guardianships and conservatorships so ripe for abuse is the extensive power that is typically granted. A professional guardian of a person and their estate is able to directly bill their estate (sometimes, for outrageously large amounts or unnecessary services), sell their home and assets, and decide where they’ll live and who’s allowed to see them. And all of this is executed with very little oversight.

Elaine Renoire’s grandmother, who was placed under guardianship after suffering a stroke.

Elaine Renoire, president of the National Association to Stop Guardian Abuse, was inspired to help form the organization after her 97-year-old grandmother, who’d suffered a massive stroke, was placed under guardianship in Indiana in the mid-1990s. While Renoire was the guardian of her grandmother’s person for the 12 years up until her death, a bank was appointed guardian of her estate. Renoire said the bank would deny funds for her grandmother’s comfort and occasionally even her medicine. “It was the worst thing in the world,” said Renoire, who spent an estimated $20,000 unsuccessfully fighting the measure. “Because it was my grandmother, and I loved her dearly.” As president of NASGA, Renoire now counsels individuals around the country seeking help due to guardian and conservator abuse.

While the extent of guardian abuse is unknown, individual reports indicate that it’s much more common than one would like to think. A November 2010 report from the Government Accountability Office documented hundreds of allegations of guardian abuse over the prior two decades including physical abuse, neglect and financial exploitation. In a 2016 GAO report, cases highlighting professional guardians included one in Ohio who misappropriated funds to support his drug addiction; another in Texas who was responsible for more than 50 wards and failed to contact them for months or to provide them with shoes or clothing; and a third in Oregon who mistreated or stole money from 26 people.

Little Protection From the Courts

After Erica Loberg’s father died suddenly of cancer in 2016, her mother, who was mentally competent but unable to handle the financial accounts previously administered by her father, was placed under a professional conservatorship in Los Angeles, responsible both for her person and her estate. Loberg had come across allegations of abuse by this conservator on NASGA’s website, but when she tried to present them at the hearing, she said the judge wasn’t interested and awarded the conservatorship regardless. “Literally the day we got attached, all the belongings were taken from the house,” Loberg said. “That’s when it became real, because everything was taken. The wine cellar was wiped out, all the furniture, all the paintings, all the china, all jewelry, everything in my bedroom — all the family pictures. It was all gone within a day.”

Fearing the worst — that the conservator was preparing the house for eventual sale, after depleting her mother’s assets — Loberg filed reports with everyone she could think of, including the fiduciary bureau and even the FBI. She was furious when her mother was hospitalized for dehydration and she didn’t find out about it for days, as well as when the conservator attempted to file a restraining order against her. Loberg’s first big break, she said, came when she asked the probate attorney’s office to look into the case and interview her mother, and the woman conducting the assessment determined that the conservator was not a good fit. Eventually, after a year and a half, her mother was removed from his conservatorship and placed under a different conservator, one that Loberg approves of. “Without that report, I don’t think I would have ever been able to accomplish anything,” she said.

Professor David English

David English, a professor at the University of Missouri School of Law, said that while most states’ statutes require that guardians only be appointed if there’s no less restrictive alternative available, in practice that requirement is often ignored. Courts rarely grant a limited guardianship — which would, for example, permit an individual to retain their own checking account, while their property is managed by a guardian or conservator — likely because it’s more complicated. “The whole system pushes for the appointment of a full guardian,” English said. One common way for elders to come under guardianship is when they enter a nursing home, and the institution insists that someone competent be appointed who can be financially responsible, he said. Another might be when an individual is being financially exploited.

“The issue number one is, is the guardianship necessary in the first place?” English said. “Then the second issue is, who should be appointed as guardian? And that’s a difficult question. Because the horror cases in the news tend to be professional guardians, most of whom are quite responsible. But, you know: Some are not.”

Dealing With the Aftermath

The cover for a book of poetry, authored by Loberg, about her mother’s conservatorship

Loberg said that one of the most challenging aspects of her mother’s conservatorship was that all of this upheaval occurred while she was mourning the loss of her father. “I was just trying to literally survive, just getting through mourning and the grief process,” Loberg said. “And so when [the conservator] came in out of nowhere and all this stuff was happening, it was just like shock after shock after shock.” Her father hadn’t left a will or trust, and there had been no conversation around how to best support her mother. Loberg couldn’t come to an agreement with her two sisters over what to do next; she, like Kelly, believes that the conservator exploited their situation. “He preys on families that have some havoc going on,” she said. “You really just have to have the tough conversations. If my family had done that, this never would have happened.”

Kelly said she no longer speaks to her sister; she also lost her relationship with her niece. “She’s the only sister I have,” Kelly said. “I never wanted anything to come between us.” While the conservator spent an estimated $100,000 of her mother’s money, Kelly said, she spent just as much herself on attorneys. At one point, Kelly said, she and her mother decided to oppose some of the conservator’s accounting — which charged for things such as tax preparation that hadn’t been provided — and while they were successful, they lost just as much in attorney and mediator fees. Another time, Mann called Kelly saying that someone had withdrawn $30,000 from an investment account; it turned out to be the conservator. While Mann’s name was on the letter requesting the withdrawal, an independent forensic analysis paid for by Kelly found that Mann’s signature on the document was most likely faked. None of this money was ever recovered. Meanwhile, despite three separate doctor’s notes in support of Mann’s competency, as well as a new driving test on which she obtained a score of 100%, Mann’s conservator wanted a separate medical opinion, from a doctor she’d chosen — a request Mann refused. “I’m not incompetent, I haven’t committed any crime,” Mann told CBS. “It’s just that someone’s trying to steal my money, and make me incompetent.”

Martha T.S. Laham, author of “The Con Game: A Failure of Trust,” which explores various forms of elder abuse in the U.S., wrote that “like a train wreck waiting to happen, loved ones are helpless in preventing a conserved family member from having his or her estate bled dry and in stopping him or her from being subjected to unwanted medical treatments.” To avoid the nightmare experienced by Kelly and Loberg and their mothers, Laham said, elders should engage in advance planning — drafting a will; setting up a trust; and perhaps most importantly, establishing a power of attorney. (While it’s possible to identify a person to serve as guardian, this may also make one more likely to be placed under guardianship.) “In many cases where there are married couples, they just think this is going to be taken care of,” Laham said. “Many people don’t like to discuss their personal financial affairs with others. They don’t want to spend the money on a professional, or they feel their estate is too small to justify professional assistance.” Unfortunately, those without assets are also at risk of losing their rights, as courts in many states can appoint a public guardian in the absence of willing and responsible family members or friends, she said.

After watching what her grandmother and others have gone through, Renoire, the NASGA president, clarified in her own legal documents that she does not want a guardianship under any circumstances, while listing multiple successor power of attorneys. “I’m making every effort to avoid a guardianship and I do not authorize it,” she said. “And I give my power of attorney my blessing to fight against the guardianship.” Renoire said that NASGA supports the Uniform Law Commission’s “Guardianship, Conservatorship and Protective Arrangements Act,” which has been passed by two states, and aims to better protect elders by encouraging alternatives to guardianship, while requiring that the individual in question be present at the initial court proceeding, among other measures. English, who served as chair of the law’s drafting committee, said that rather than overthrowing their current statutes by implementing the full law, many states are likely to adopt portions of the legislation; his home state of Missouri did so in some of its 2018 reforms.

Unfortunately, a guardianship, once instated, is not easily overturned. English recommends that family members of a loved one in an abusive professional guardianship make a complaint to Adult Protective Services, while also writing a letter to the judge — which, depending on the judge, may inspire the court to take action. Loberg advises others follow her footsteps in seeking an assessment from the probate attorney’s office. Joe Roubicek, a detective with the State Attorney’s office in Florida who spent more than 20 years at the Florida police department, largely in the area of elder fraud, recommends that if an elder is being abused for any reason, their loved ones call Adult Protective Services to perform an investigation — though this could also result in an unwanted guardianship, if one isn’t already in place — or even go directly to the police. Roubicek, who personally arrested a notoriously abusive professional guardian named Martha Wright in the 1990s and has been emotionally impacted by the elder abuse he’s witnessed over the years, said that as he ages, he plans to stay as active and involved as possible to avoid an unwanted guardianship or elder fraud. “Don’t get too comfortable on the couch,” Roubicek said. “Get up and get out and live, because you’re going to fade away.”

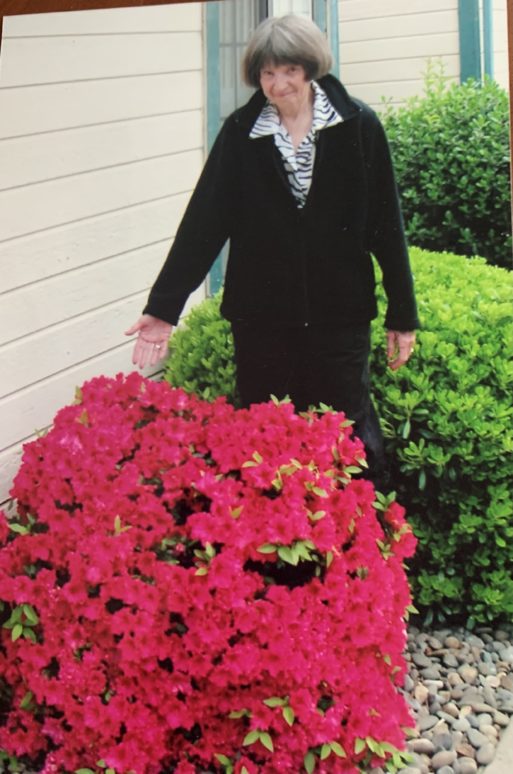

Mann loved to garden, and was known to have a green thumb.

Credit: Courtesy of Carol Kelly

Still, if those as active and as competent as Mann are at risk, there’s far more work to be done. Teaster would like to see improved data collection — which would, most likely, need to happen at the state level. Both Teaster and English took part in a recent National Guardianship Summit — the fourth to be held since 2011 — in which attendees drafted a lengthy set of recommendations to improve autonomy and accountability, including the creation of a bill of rights for adults under guardianship, meaningful access to due process, and a process for rights to be restored.

For Mann, however, such measures come too late. “What’s happened to our system?” she asked CBS, a year before her death. “They just want to destroy me, that’s all. And in some ways, they are.”

Guardianship or Exploitation? How Conservators Abuse the Elderly

Guardianship or Exploitation? How Conservators Abuse the Elderly

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”