- Parents are intimately involved in the care of children with cancer. A proposed new study seeks to tap into their expertise.

Researchers at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health recently published a paper that involved a unique collaboration between scientists, doctors, ethicists and the bereaved mother of a child who died while in their care. Published last month in the journal Pediatrics, the paper proposes a study of medical decision-making in pediatric end-of-life care. The question the researchers hope to answer is how to better include families in end-of-life treatment decisions, such as when to discontinue chemotherapy or when to involve palliative care.

The collaboration is the brainchild of Kimberly Pyke-Grimm, R.N., Ph.D., of Stanford Medicine Children’s health, who invited the bereaved mother, Jamila Hassan, to join a nationwide research team. Hassan spent eight years at her son Omar’s side after he was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at the age of 2 and underwent multiple courses of chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant before he died at the age of 10. Her years of interacting with the health care team give her a unique perspective into the ways in which healthcare providers can support parents during what are undeniably some of the worst days of their lives.

“I think this kind of study would be an opportunity to improve small things parents remember about these important discussions or stressful times, like how a doctor or nurse talks to you slowly and calmly or helps you feel supported,” Hassan told Stanford Medicine News.

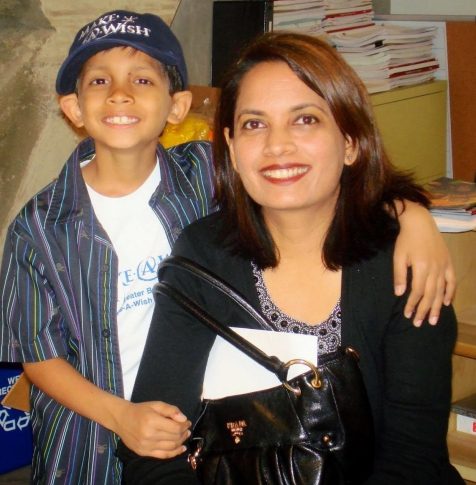

Omar Hassan with his mother Jamila before his death in 2012

Credit: The Hassan family via Stanford Medicine

An Unusual Approach

Studying end-of-life decision making in the pediatric population is difficult because researchers are typically unwilling to put additional burdens on families who are under enormous stress or grieving the loss of a child. But without family input, it’s almost impossible for care teams to know if they are providing enough of the right kind of information and support.

“It makes good sense to have them guide us, to benefit from their wisdom and experience,” Pyke-Grimm said. The challenge is to approach them in a way that puts their experience rather than the needs of the research team at the forefront of any interactions.

Kimberly Pyke-Grimm is a nurse-scientists who studies pediatric end-of- life decision making

Credit: Stanford Medicine News

“Parents may be worried about work, finances or their other children, or just having a hard day,” Hassan wrote in the paper. “Also, they may not be eating or sleeping well (child or parent), or do not want to leave their child. An individualized approach would be important.” She advocates for more flexibility in the study design, so that parents could, for example, join the study at any time rather than waiting for a research window to open up.

Other information the study might uncover are the ways in which words impact a grieving parent’s experience. For example, caregivers sometimes make well-intentioned comments that leave parents feeling even more isolated and alone. “They say things like, ‘You will be fine,’ and when you are hearing it as a parent, you’re thinking, ‘This person is saying it because it’s her job, but she hasn’t been through it herself,’” Hassan said.

The proposed study is still in the design phase, but may eventually involve interviewing adolescents and their parents about their thoughts and feelings following a discussion with care providers about an end-of-life decision. Hopefully it will be the first of many efforts on the part of the pediatric palliative care community to learn how to best serve children with a life-limiting illness and their families.

A Bereaved Mother Helps Scientists Study Pediatric End-of-Life Care

A Bereaved Mother Helps Scientists Study Pediatric End-of-Life Care

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”