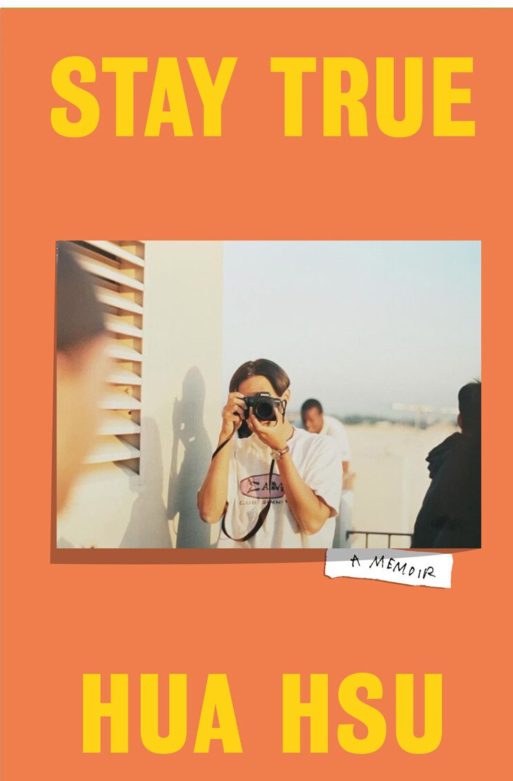

“Stay True” is a memoir by Hua Hsu, a well known writer for The New Yorker and The Atlantic on issues of race, multiculturalism,and the immigrant experience. Hsu’s latest book stays in line with these themes while also delving into his deeply personal experience of loss as a college student. “Stay True” explores what it means to grieve when your entire identity is already in flux as a young adult, and offers insight into Hsu’s path throughout his life.

“Stay True” is a memoir by Hua Hsu, a well known writer for The New Yorker and The Atlantic on issues of race, multiculturalism,and the immigrant experience. Hsu’s latest book stays in line with these themes while also delving into his deeply personal experience of loss as a college student. “Stay True” explores what it means to grieve when your entire identity is already in flux as a young adult, and offers insight into Hsu’s path throughout his life.

The central event in “Stay True” is the death of Hsu’s close college friend, Kenneth Ishida, during a carjacking. But Hsu doesn’t delve into the event until a little over halfway through the book. Instead, the first half of the book focuses on Hsu’s personal development in his early life as an Asian American born to Taiwanese immigrants. He started to craft an identity for himself in high school as an aesthetically refined finder of underground music and creator of zines, a bit of a snob who judged others before they could reject him.

In college, Hsu quickly found his prickly persona jokingly challenged by a fellow freshman, Ken Ishida. Ishida was a Japanese American, handsome frat boy with mainstream tastes. His family had been in the U.S. for generations and he appeared seamlessly integrated into American culture. To Hsu’s surprise though, Ishida was actively processing his own experiences of discrimination and identity as an Asian American. Despite their differences, they became fast friends and spent hours discussing race, movies, and music. Ishida saw Hsu’s tetchy facade as protection against social anxiety and encouraged him to step out of his comfort zone.

Their friendship was cut short, however, the summer after their junior year. Early in the morning of July 18, 1998, Ishida was accosted by three strangers looking for someone to rob. They ended up violently shooting Ishida. The random and brutal nature of his death sent shockwaves through his college friend group, and Hsu details the surreal nature of preparing a eulogy for a friend he had seen only a few hours earlier.

Author Hua Hsu

Hsu spends the second half of the book remembering his grief and reflecting on the nature of friendship and trauma. He recalls feeling guilty and blaming himself for not being there to prevent the violence, and obsessively fearing that any of his friends would now suddenly die out of the blue. He listens over and over to the popular music Ishida had loved and that Hsu had scorned, and wrote letters to Ishida about the ways life inexplicably continued without him.

The book ends with Hsu entering graduate school on the East Coast and starting therapy. As Hsu reunites with college friends and reflects on his life path, he wonders, “How much of the confusion surrounding our paths was generic postcollege stuff, and how much of it owed to how our lives had been recalibrated around these new scales of fear and failure?”

“Stay True” is a memoir unlike any other. It is rare to find someone reflecting on the traumatic loss of a friend as a young adult and the impact this has on one’s worldview during such a formative period. Hsu questions how different his life would have been if Ishida hadn’t died, or if they hadn’t met. He wonders at one point if Ishida hadn’t died, would they have stayed in touch after college or slowly drifted apart as so many friendships do, and ponders how deeply he actually knew Ishida. He recognizes that there are no answers to any of this, and all he can do is honor the place Ishida did have in his life.

“Stay True” reads as both a memoir of grief and a coming of age story, an exploration of how friendships shape our identity and how we deal with their loss. My only critique of the book is that the second half feels rushed, as Hsu narrates his grief. I would have appreciated hearing how his grief influenced him not in the immediate years after, but as he continued to navigate his twenties. Despite this, I would recommend the book to anyone who is not sensitive to descriptions of violence.

“Stay True” by Hua Hsu

“Stay True” by Hua Hsu

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead