A gathering of chaplains outside of work. Article writer Brianna Deutsch is

featured on the far right.

Hospital chaplains…. For many people, the term can conjure up images of a solemn pastor dressed in black, informing families that their loved one has died or offering prayer at inopportune moments. But prayer and grief support are only a small fragment of what hospital chaplains do. Having worked as a hospital chaplain for the past two years, I can offer some insight into the most common assumptions, misconceptions and little-known facts about chaplaincy.

First, a little background on hospital chaplaincy. Faye Getz wrote in her book, “Medicine in the English Middle Ages,” that hospitals were linked with religion from the beginning. The earliest hospitals were less focused on saving lives or curing disease, and instead existed to allow the pious to practice Christian charity and feel good about themselves. Medicine was limited in its uses, so hospitals were run by churches as places where the sick or disabled who were too poor to live at home came to die. Christopher Swift reported in his book, “Hospital Chaplaincy in the Twenty-First Century: The Crisis of Spiritual Care on the NHS,” that historically, spiritual care often was seen as more important than medical care, since illness was believed to be caused by sin. The main task of medical doctors at the time was to persuade the sick to see a priest. Hospitals in early modern France were known as “hotel Dieu,” or God’s hotel. Swift detailed how even after hospitals began to become separate foundations from the church, they continued to retain the religious influences that had formed them, and moral restoration through “treatments” like confession was seen as just as important as physical healing.

In the early United States, this link between religion and medicine continued, albeit from much more of a Protestant focus. Wendy Cadge’s book “Paging God: Religion in the Halls of Medicine” explores how many early American hospitals required patients to attend church services on Sunday and forbid card-playing and other “morally depraved” activities. Early chaplains were retired or volunteer clergy from Protestant denominations and often unequipped to handle Catholic or Jewish patients. Specific Catholic and Jewish hospitals began to emerge after the Civil War to meet the needs of these communities, who feared proselytization at more Protestant-affiliated hospitals. Eventually in the 1920s, programs started to develop to train chaplains in the hospital, and chaplaincy became its own career,

Today, most hospitals have chaplains. In 2019, the Washington Post reported that 20 percent of the American public said they had worked with a chaplain or had been contacted by one in the last two years. This is happening at the same time as religious attendance is falling across the U.S.; in 2019, more Americans said they attend religious services a few times a year or less (54%) than said they attend at least monthly. As more Americans forego organized religion and places of worship, Shelly Rambo, theologian and chaplaincy researcher, predicts that “Religious leadership in the United States in the future is going to look something like chaplaincy,” where the only interaction people have with trained religious leaders is in places like hospitals, prisons, and other similar locations.

In today’s multicultural, pluralistic world, hospital chaplains occupy a unique territory. Hospitals are secular spaces but fraught with emotion, questions of purpose and meaning, and forced confrontation with our own mortality. Chaplains exist to provide spiritual care in this space, which can and should look very different from spiritual care in a specifically faith-based congregation or community. Given all of this, let me debunk the most common misconceptions about hospital chaplains.

1.) Not all chaplains are Christian or even religious.

While the majority of chaplains do come from a Christian background, it is also common to find chaplains who identify as Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist or another religion. There is also a growing movement to endorse chaplains who are specifically non-religious and define themselves as humanist, agnostic or atheist. Chaplains from non-religious backgrounds still face an uphill battle as the endorsing organizations adjust to cultural changes in what it means to do non-traditional spiritual care.

Chaplain Jean Walters identifies as an atheist and spoke with me about how she wants to encourage everyone to examine unconscious biases towards non-religious patients and chaplains themselves. Walters described how often evangelical patients would exclaim in shock if they discovered she was atheist and would sometimes try to convert her. But Walters argued that her non-religious background helps her get to the heart of who someone is rather than rely on preconceived ideas: “I am atheist in terms of I don’t believe in a theistic deity but it doesn’t mean that I believe nobody should believe in this…. I’m not there to tear down their ideas of religions. I assess someone against a worldview approach, in terms of how they identify right and wrong, how they make meaning. Even though they’re Christian, what does it mean to them to be Christian? Instead of making assumptions based on a label, it gives us a starting point of seeing the person as they are in their uniqueness. I see them in the multitude of their identities and how they intersect.”

Chaplain Jean Walters enjoying free time

2.) Good chaplains do more than just pray.

Similar to assumptions about chaplains’ religious backgrounds, people often assume chaplains only exist to provide very traditional religious care. This was the first thing mentioned by every chaplain interviewed and is the biggest misconception people generally have about hospital chaplains. Because of the historically Christian context that created chaplaincy, people often assume that chaplains are simply church pastors lurking in disguise, eager to offer a prayer or Bible passage. I am happy to pray if that is something meaningful to the patient or family, but chaplaincy that becomes dependent only on prayer or traditional Christian symbolism is both lazy and ineffective.

The best chaplaincy is innovative and focuses on big picture meaning-making. What does it mean to live with a serious illness? What matters most after a terminal diagnosis? What supports you in difficult times? As a chaplain, I am always interested in the person’s religious background and beliefs in the context of questions around meaning-making, but have also had deeply meaningful visits that have nothing to do with traditional religion.

For instance, I recently had a conversation with a man whose leg had been amputated after years of operations and limited mobility. He talked about the phantom pain he experienced when taking his first steps after surgery, and became tearful talking about how he had been protective over his leg for years. We talked at length about what it meant to say goodbye to his leg, to offer gratitude for the ways it had supported him and carried him to this point, and then to acknowledge that he was now entering a different phase of his life. Chaplaincy should offer a space to explore what it means to be human in our fragile bodies, living in a world that is both terrifying and wonderful.

3.) A Good Chaplain Focuses on “Meaning-Making” First and Spirituality Second

Chaplains are trained to provide interfaith spiritual care and should have a basic knowledge about rituals, customs and beliefs across a spectrum of world religions. Many spiritual care departments will distribute resources to help patients participate in Ramadan, Passover or other religious celebrations. But beyond just this, hospital chaplaincy can and should engage people who don’t identify as specifically religious or spiritual, but who are wrestling with what it means to be a human with a body and emotions. There can be a huge amount of grief associated with a life-limiting illness, or a pull to reassess priorities in their life, and this can happen with or without a religious framework.

Chaplain Rev. Michelle Wright, Ph.D. spoke with Michigan Medicine about her perspective: “Whether a person comes from a religious background or not, everyone has some way of making sense of his or her life. It’s what we call “meaning-making,” and it’s prevalent in the lives of most individuals. Many people may not realize it until something disturbs how they see the world and themselves in it. When a person is having health concerns, their sense of who they are may change. They may no longer have a sense of purpose, or they may wonder why this is happening to them.” Rev. Wright’s insights are also corroborated by a recent Gallup poll that found that in patients and families who had met with a chaplain in a healthcare setting, the most common things discussed were death and dying, emotional and mental health, dealing with change, and dealing with loss.

Chaplaincy should hold space for both the big picture questions and the small reminders of who someone is outside of their hospital stay. I had a patient tell me recently that she was so grateful for a visit from my colleague where all they did was talk about fashion and clothes. The patient shared, “That conversation was the first time in weeks I actually felt like myself, the me I am when I’m not sick.” The chaplain engaged the patient in a reminder of her passions, her sense of self, and hopes for what she wants to reclaim when she leaves the hospital. All of this is excellent spiritual care, although it doesn’t fall into traditional religion.

Patients may find themselves asking big questions like, “Why me?”

Chaplains can help explore this.

4.) A good chaplain will not proselytize anyone, and patients have a right to complain if they feel discrimination from a chaplain.

Most hospitals and chaplaincy organizations have rules that specifically prohibit chaplains from forcing their own belief systems on patients they serve. The largest organization that certifies chaplains, the Association of Professional Chaplains, specifically states in its Code of Ethics that “Members shall affirm the religious and spiritual freedom of all persons and refrain from imposing doctrinal positions or spiritual practices on persons whom they encounter in their professional role as chaplain.”

There is some room for interpretation within this, however, and the guidelines and limits on this remain murky. For instance, a Catholic chaplain was recently awarded $12,000 in a lawsuit against the London National Health Service Trust after he was let go from his job for sharing Catholic teachings on same-sex marriage with a patient. In 2019, a patient at Springfield Hospital requested to speak with a Catholic chaplain. The patient shared that he was in a gay relationship and that he wanted to marry his partner, but his father was irate about this. He asked the chaplain what the Catholic Church’s stance was on same-sex marriage. The chaplain asked the patient to consider what God would say about this, and encouraged him to see his father’s viewpoint.

The patient filed a complaint with the hospital, and after an investigation, the chaplain was dismissed. The chaplain then sued the hospital for religious discrimination, arguing that he had simply presented Catholic Church teachings honestly when asked, and he was awarded the $12,000 fine in his favor. As this case highlights, it is complicated to determine what constitutes imposing religious doctrine on patients, but evangelization by chaplains is considered a disturbing breach of ethics that should not be happening.

5.) If we show up, it doesn’t automatically mean that someone is dying.

People strongly associate chaplains with bad news, or believe that if the chaplain gets involved, it must mean the doctor is too afraid to tell them that they’re dying. The faces of patients often pale by several degrees when I introduce myself, and they later confess that they saw their life flash before their eyes in fear. One colleague shared that she deliberately avoids wearing all black at work because she doesn’t want to encourage the perception that she’s some kind of angel of death, and another chaplain shared that a patient once jokingly referred to her as the Grim Reaper. Chaplains do often routinely get called to the bedside of people who are dying, sit with families if their loved one’s heart stops and doctors are working to revive them, or facilitate end-of-life conversations and rituals. But that is not all that we do, and just because a chaplain stops by your hospital room, it doesn’t mean all hope is lost.

In reality, chaplains are a routine part of the care team in hospitals. In hospitals that are well-staffed, it is common for chaplains to round and introduce themselves and Spiritual Care to most new patients, regardless of disease or prognosis. Often nurses may ask the chaplain to visit if the patient is nervous or struggling emotionally and could use a listening ear. Sometimes nurses will refer a chaplain to someone just because the patient is a lovely person and will make for a good conversation. There are many reasons why a hospital chaplain might offer to connect with a patient and it is not an automatic sign that they are dying.

Chaplains can provide comfort in times of distress, but are not always the bearer of bad news.

6.) We are used to getting a wide variety of responses when we introduce ourselves.

It is always interesting to see the range of reactions people have to a chaplain walking into their room. Sometimes people welcome you with open arms and delight, exclaiming over how wonderful it is to have a spiritual guide visiting. Other people physically recoil or react, because they have negative associations with religion. I once walked into a room and the patient eagerly shouted, “The fact that you are here is proof that Jesus is real and God loves me!” It turned out that she had desperately needed to use the bathroom with nursing assistance, but had dropped the button that would let her summon help. She had been praying for 20 minutes for someone to come help her, and saw my entry as divine intervention.

As spiritual care providers, we can often become a stand-in for their relationship with the divine, a visible representation of God or religion. For people who have had pain or trauma caused by religion, chaplains may be an unwelcome reminder of their past or viewed as intrusive. Patients who are agnostic or atheist may be uninterested in anything that feels closely tied to religion. If a patient or family declines a visit, I do not take it personally and gladly respect their request.

7.) Our visits are not confidential and we serve as part of the interdisciplinary team.

Patients sometimes assume that chaplain visits are completely confidential in a manner similar to how confession with a priest is confidential. In reality, chaplains function as a part of the interdisciplinary team and share information as needed with other providers to help coordinate the best care possible. This is done in part because chaplains can offer a more holistic view of the patients and their priorities and can make sure their humanity doesn’t get lost in the sea of medical decisions and lingo. Patients may not understand why their care team has such an analytical focus, while providers may question why a patient doesn’t seem to grasp the reality of their illness.

Chaplain Doria Charlson, Ph.D., shared, “I have found that my role as a chaplain is really that of an interpreter. I am often the only ‘multilingual’ team member: I can speak to the values and priorities of the patients, while also honoring and communicating clearly regarding the clinical and emotional concerns of the staff. Sometimes these are in conflict, but more often I have found that our goals are aligned, it’s about finding the language to recognize that alignment.” Chaplains can help navigate between the patient’s values and the medical decisions that have to be made.

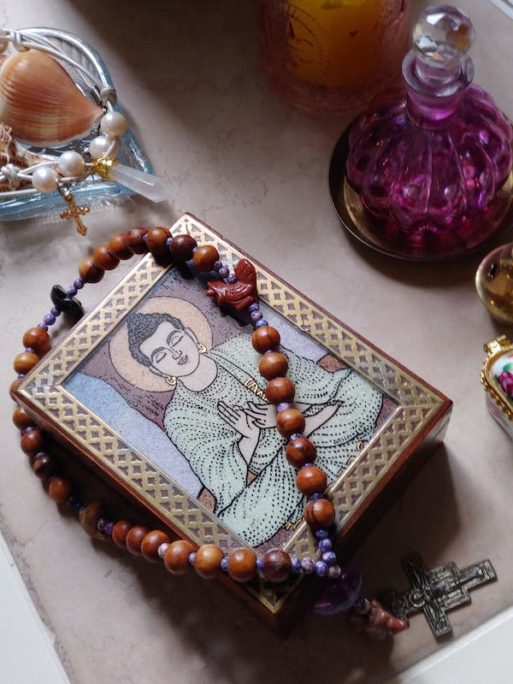

Chaplain Doria Charlson hosts multicultural celebrations of spirituality.

8.) Chaplains are found at most hospitals, but the background and qualifications may differ.

Most hospitals have some kind of chaplain available. The Joint Commission, an organization that evaluates and accredits hospitals, specifically recognizes a patient’s right to receive appropriate spiritual and religious care, and encourages hospitals to have chaplains. A 2015 article in the Association of American Medical Colleges found that 70% of hospitals provided some kind of spiritual care.

Although widely available, the quantity of chaplains can vary greatly depending on the hospital. Some hospitals rely on volunteers, who may be retired clergy or lay people with a desire to help out. But volunteers often lack specialized training in providing spiritual care across belief systems, and may be more strongly motivated by a desire to help people of their same faith (for instance, many hospitals utilize volunteers to distribute the Catholic Eucharist if priests are in short demand). Volunteer chaplains are typically supervised only within their own hospital, and are not accountable to any broader ethical committee. They may not be provided time or space to reflect and hone their skills as a chaplain.

To counter this, there are formal programs for chaplaincy training that last for one summer or an entire year. These programs, called Clinical Pastoral Education (CPE), allow someone to work as a chaplain while receiving training in spiritual care, interpersonal dynamics, ethics and self-reflection. Many hospitals require their staff chaplains to possess at least one unit of CPE, as a way of knowing that their staff are properly trained.

For the most competitive chaplain jobs, chaplains can seek to become board certified after completing a year of CPE and working an additional 2,000 hours. Board certified chaplains must have graduate degrees in religion, psychology or a related field, and must write essays demonstrating competency in areas such as ethical principles and knowledge of human development in regards to spiritual care. After submitting these essays, the chaplain must defend their answers and provide other examples of spiritual care in front of a committee. It is a lengthy process to become board certified, and because of this, not all chaplain jobs require it. While there are valid critiques of CPE and board certification (mostly stemming from the ways both were formed by Christian principles from the early days of chaplaincy), these processes can also help ensure high quality spiritual care that meets people where they are.

Chaplains are trained in providing interfaith spiritual care.

9.) Chaplains use evidence-based spiritual assessment models to evaluate patient needs and offer appropriate spiritual interventions.

When chaplains walk into a room to meet with someone, they should ideally be doing more than just having a nice conversation. Chaplains are trained in different models of spiritual assessment that can offer insight into the patient or family’s spiritual needs and guide the response of the chaplain accordingly. There are various assessment models, but most tend to look at the person’s spiritual or religious framework, support system, existential distress and fears.

One popular model is the Spiritual Assessment and Intervention Model (AIM), which posits that humans have three core spiritual needs: meaning and direction, self-worth and belonging, and to love and be loved. AIM offers a guideline for how to assess what someone’s spiritual need may be, such as needing reconciliation with a loved one, or help making a decision about treatment options. AIM also lists recommended spiritual interventions that a chaplain can do, such as guiding someone in a life review or holding space for anger.

10.) We are not saints and have a life outside of work.

Working as a chaplain does not automatically give someone spiritual enlightenment. While we hope that chaplaincy training spurs self-reflection and internal growth to handle conflict in healthy ways, chaplains are still humans and are not immune to petty frustrations, exhaustion or disagreements. We make mistakes, just like anyone else. Some of us need coffee to function, or get hangry without lunch. While many chaplains experience deep joy and fulfillment in their job, it does not remove the stressors of daily life, and it can be challenging work.

Many chaplains find it necessary to develop rituals or self-care regimens to help them recharge after work. While some chaplains are engaged in religious ministry in their free time, many others do not want to feel like a chaplain outside work. Friends, family, acquaintances, and strangers may suddenly start to divulge their greatest fears or traumas because chaplains tend to be good listeners. I am personally always wary of protecting my energy outside of work and not doing unpaid emotional labor for others. One chaplain mentor compared it to someone who works as a baker. They may occasionally bake a cake for their friend’s birthday or celebration, but they aren’t routinely baking for free 24/7. Similarly, many chaplains are cautious about their free time. And while they may be grounded in a spiritual community, they may or may not want to take on a leadership role or listen to other people’s feelings and trauma outside of work.

Chaplains need down time outside of work.

11.) We are available for not just patients, but also staff.

Being a healthcare worker is a hard job, especially after a global pandemic. It can be emotional or demoralizing when patients die or teams are short-staffed and working extra shifts. Chaplaincy is available as a support for not just patients and families, but also the staff who care for them. When staff are faced with personal or family issues outside the hospital, chaplains are available to talk with staff as needed. Chaplains often coordinate annual memorial services to honor patients who have died, and also often offer room blessings after challenging cases. When a staff member falls ill or dies, chaplains offer grief support to their coworkers.

In many hospitals, chaplains are coordinators for calling a Code Lavender, which is a call for intensive staff support after a distressing event. Rabbi Susan B. Stone writes in Nursing magazine about facilitating a Code Lavender event both immediately after an unexpected and traumatic patient death by creating space for disbelief and tears, and then scheduling a longer debriefing session in the following days to help make sense of the death. She facilitated calling a Code Lavender as a sort of psychological first aid for staff. Throughout the hospital, chaplaincy is an added layer of support available to all.

In Conclusion

While many people interact with a hospital chaplain at some point in their life, they may not realize the thought, training and intentionality that goes into spiritual care. Assumptions based on chaplaincy’s long history as Christian pastoral care obscure the wide range of creative spiritual care happening today. Hospital chaplaincy today is more expansive than ever before, and focuses on meeting people as they are rather than changing their beliefs. Chaplains can be an invaluable resource for patients, families, and staff in the hospital setting.

A Hospital Chaplain Debunks the Most Common Misconceptions About Their Role

A Hospital Chaplain Debunks the Most Common Misconceptions About Their Role

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One