Modern grief theories emphasize that grief is a fluid nonlinear process, and no two people grieve in exactly the same way.

Credit apa.org

If there is one thing people know about grief, it’s that there are five stages you must move through. Or are there? Elisabeth Kubler-Ross’s model of grief has become by far the most well-known, commonly cited paradigm for grieving, but the widespread acceptance by the public has been riddled with misinformation. Throughout the years, grief theories have evolved just as the general public perception of grief has changed as well. In recent years, more and more people are calling to recognize the wide variety in grieving and move away from formulaic prescriptions of what normal grieving looks like. Our ideas about grief have become more expansive, giving us different language to articulate the meaning of loss.

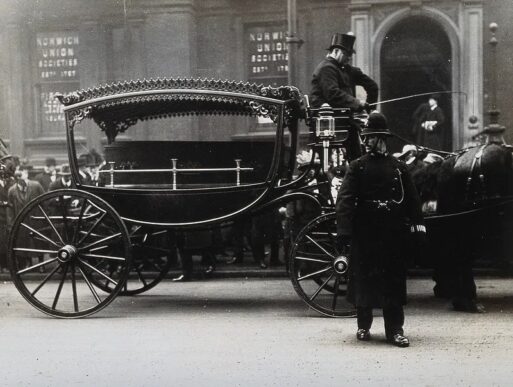

Historical Grief Theory: Rooted in Detaching from the Deceased

Grief theory didn’t start with Kubler-Ross, but instead traces back to the father of psychology, Sigmund Freud. Freud published his article “Mourning and Melancholia” in 1917 that theorized that the work of mourning is to detach from the loved one that has died. When this doesn’t happen, mourning can escalate into melancholia, which Freud viewed as a deeper, persistent state of depression. Freud believed the bereaved must learn to accept their new reality without their loved one if they wish to form newer emotional bonds with others. While we may view some of his ideas as a bit harsh through the lens of our own era, Freud also emphasized that mourning was a natural act and that unless it reached melancholia, grief wasn’t pathological or automatically in need of treatment.

The next person who contributed significantly to the lexicon of how we conceptualize grief was Dr. Erich Lindemann, a psychiatrist who was working at Massachusetts General Hospital in 1943. He was called in to assist after a popular Boston nightclub, Cocoanut Grove, suffered a massive and deadly fire that left 492 dead in its aftermath and hundreds more traumatized. Lindemann’s experience supporting the grieving survivors inspired him to build upon Freud’s earlier theories of mourning, and to emphasize that the bereaved must complete “grief work” to move forward. He published “Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief” in 1944, positing that “grief work” involved letting go of ties to the deceased, adjusting to the new environment of loss, and forming new relationships. Lindemann’s work bred the idea crisis theory and solidified the idea that grief was an unfortunate reaction to loss, but could be worked through by following the right steps.

The Most Popular Grief Theory of All: Five Stages

Twenty-five years later, Kubler-Ross published her book On Death and Dying after working with terminally ill patients processing what it meant to be at end-of-life. She suggested that patients facing their own mortality moved through stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance; it was only later that her work was expanded to include bereaved family and friends. Out of all grief theories, this one has by far had the biggest cultural impact, entering the cultural conscious so thoroughly that people sometimes joke about which of the five stages of grief they are in for things that are minor inconveniences. The widespread appeal of this theory has caused it to be the dominant way many people believe grief should be expressed. Dr. Mary-Frances O’Connor articulated to the Washington Post the danger in this: “The trouble is, what was a description of grief became a prescription for grieving.”

Grieving people still sometimes fixate on forcing themselves to try and move through the different stages step by step, hoping for the promise at the end that they will finally feel better. Writing for The Atlantic, grieving mother Hilda Bastian shared the pressure she felt from the Five Stages Model of Grief: “Though I’d been a fan of Kübler-Ross’s work, mentions of this theory caused me stress when I was in extreme grief. Was my denial “stage” over yet? If not, how long did I have before I’d turn into a rage monster and scare my grandkids? Some grief websites warned that people can move backward and forward through the stages as they grieve — an idea that made me worry that the all-consuming despair could return. That possibility nipped at any sense of hope and encouragement I could muster: My anxiety would ebb, but then the internet whispered, It won’t last.” Bastian is not alone in her criticism of the Five Stages. Kubler-Ross herself later went on to critique her own work and offer the idea that these stages “are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order.”[1]

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

Photo Credit: ekrfoundation.org

Despite this, many people still cling onto the Five Stages of Grief. A 2021 survey published in Death Studies found that 65% of the general public believed the statement, “The process of grief can be expected to progress through a predictable series of stages, starting with denial and ending with acceptance,” was definitely or probably true. Because the Five Stages of Grief theory took off so widely in public society, it can be presented in ways that don’t do justice to the nuances of what it means to grieve. A 2021 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that when Googling, 61% of sites that provide information for grieving after the death of a loved one centered on discussing the Five Stages model, with 34% of those sites dedicating over half of their text space to only the Five Stages model. The authors found that the majority of sites presented the model without talking about any limitations, critiques, or presenting any contemporary alternatives. The study authors warned that such “definitive and uncritical portrayal of the model may give the impression that experiencing the stages is the only way to grieve.” The enduring appeal of Kubler-Ross’s 5 Stages Model lives on.

Stages, Tasks, and Beyond: A New Phase in Grief Theories

Many grief theories that followed Kubler-Ross continued to emphasize the different stages of grief work that need to be done. William Worden came up with the Four Tasks of Grieving, while Theresa Rando then offered a stage model of grief called the Six R’s. But in the 1990s, grief started to be seen as a more fluid, ongoing process. Stroebe and Schut put forward their Dual Process Model that suggested that instead of tasks we move through, we instead oscillate between loss-oriented or restoration-oriented activities. Around that same time, Klass, Silverman, and Nickman published their book “Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief.” Going against the grain of Freud’s original belief that grief work fundamentally involved severing attachment to the deceased, the Continuing Bonds theory instead posited that it is normal and even healthy for bereaved individuals to maintain a connection to the deceased. This helped signal a huge shift away from grief theories based on stages and tasks, and instead seeing grief as an ongoing legacy and connection building with the deceased in new ways. Nancy Frumer Styron, psychologist and clinical director at the Children’s Room, framed it to the Washington Post this way: “Whether you want it to or not, life goes on. So the question becomes, how do I take this piece that has happened and integrate it into my life in a way that is part of me but doesn’t define me.”

Grieving mother Paula reflected to the Courageous Parents Network about the ways that she maintains continuing bonds to her deceased daughter Lydia, stating, “In the beginning, you feel like you’re never going to get through it, it’s such a great loss. But you find a way to use your circumstance to extend their life, which I guess sounds a little crazy.” Paula has worked on memorializing her daughter’s legacy by incorporating her artwork and words at her school, and shared that, “Through this grieving process, anytime I can use Lydia’s words, her art, her stories, her love and put it out there in the world in some way, then it’s a gain for Lydia. It’s like planting seeds in her garden, her life keeps growing.”

The Impact of Grief Theories on Grievers

So how have all these grief theories impacted how the bereaved understand their own grief? As Dr. Joanne Cacciatore, professor at Arizona State University and founder of MISS Foundation, discussed in an interview, the general public isn’t really interested in most grief theories. Even as a therapist, she finds it helpful to have different frameworks of grief to help understand what that person’s specific loss might mean to them, but she tries to just be present to patients in the moment. She believes that it can be extremely isolating when people start to perpetuate myths of “normal grief,” and pathologize feeling grief over long periods of time.

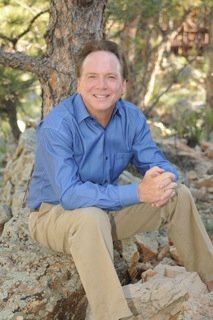

Dr. Alan Wolfelt, founder and director of the Center for Loss and Life Transition, explored the lasting legacy of the foundations of grief theory in an interview. He believes that many of the grief theory models are based in the idea of grief as a crisis moment, temporarily disrupting a life of emotional homeostasis. He posits that models like this see grief and the emotions around it as something to be surmounted so the griever can return to their normal homeostasis. Grief starts to be seen as something that is treatable rather than transformative. Dr. Alan Wolfelt argues that we can never return to our emotional homeostasis from before the loss because our lives are irrevocably changed. Instead, he advocates for what he terms the “slow grief movement,” that embraces that each griever’s journey is life-changing, unique, and cannot fit into quick timelines, tasks, or models.

He elaborates on this idea, sharing, “The emotions of grief are often referred to as being “negative,” as if they are inherently bad emotions to experience. This judgment feeds our culture’s attitude that the emotions should be denied or “overcome.” Emotions are not bad or good. They just are. What makes grief intractable in our “be happy culture” is how we have become intolerant of hurt, pain and suffering. When we lose an understanding of how life losses bring about the need to openly and honestly mourn we begin to see a desire for “quick fixes.” But this societal introject that confuses efficiency with effectiveness only naturally complicates and inhibits the human emotions that come with authentic grief. In my experience many medical model proponents have a difficult time sitting with people who are in the liminal space that grief invites the mourner into. Therefore, techniques are created to get rid of grief as quickly as possible instead of honoring the inherent wisdom that comes the need to mourn openly and honestly.”

Dr. Alan Wolfelt

Photo Credit: centerforloss.com

However, others have proposed a different model for healing after grief. George Bonanno has focused on what he terms a “resilience trajectory”: the idea that after an adverse or traumatic event such as loss, there is a brief period of disequilibrium, but then a return to healthy functioning. Bonanno suggests that resilience after grief is much more common than we think. In his 2004 article “Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience,” published in American Psychologist, Bonanno makes the case that “Many people are exposed to loss or potentially traumatic events at some point in their lives, and yet they continue to have positive emotional experiences and show only minor and transient disruptions in their ability to function. Unfortunately, because much of psychology’s knowledge about how adults cope with loss or trauma has come from individuals who sought treatment or exhibited great distress, loss and trauma theorists have often viewed this type of resilience as either rare or pathological.” He goes on to present research finding that after interpersonal loss, resilience is common and can be very healthy, and is connected to developing traits like hardiness (commitment to finding meaning in life, belief that one can influence their surroundings and circumstances), self-enhancement, and positive emotion and laughter. In Bonanno’s book “The Other Side of Sadness,” he quotes a young widow reflecting with surprise on how well she coped with the grief: “I expected to collapse, I really did. That’s what I wanted to do. That would have been the easiest thing to do … But … I couldn’t. Each day I got up and did what I had to do. The days passed and somehow it was OK.” Bonanno’s research presents an alternative to life being completely bleak after grief.

Continued Discomfort with Grief

Some, however, warn that Bonanno’s research around resiliency after grief can be used as a weapon by a society that is still largely uncomfortable watching others grieve. It is distressing to see someone in pain, and there can be a push for grievers to let go of their suffering or wrap up their grief in a timely manner. Therapist Megan Devine witnessed her 39-year old husband drown in 2009. In a conversation with Slate, she reflected, “I realized that what we say to people when they’re in pain isn’t necessarily helpful. I heard so much stuff from friends, from family members, from fellow therapists just around resilience, around bouncing back, around not letting his sudden death “wreck my life.” When people would say, “You’re so strong and you’re so smart. You’re going to find a way to get through this,” the way that felt for me was, “Don’t feel the way that you feel. Stop letting this upset you.” I actually overheard people in coffee shops say, “She must not have been a very good therapist if something like this upsets her.” We just really believe that our job is to cheer somebody up, so I was on the receiving end of a lot of cheering up. It does have that effect of making you feel invisible.”

Witnessing the grief of others also forces us to confront on just our own mortality, but the mortality of those we love. Dr. Joanne Cacciatore explains, “As a society, there is more discussion around our own death than around grief. Through things like death cafes, more people are talking about their own future death, but we’re still not good as a society talking about grief. I hear all the time from grievers who still feel like people are avoiding them, running the other way in grocery aisles when they see them. This is particularly true for catastrophic loss, such as death of a child. It’s too hard for parents to confront the reality that children die and this could happen to their child. Death can be so random and unpredictable and untimely, it’s quite difficult to confront this reality.”

Dr. Joanne Cacciatore at the Selah Care Farm

Credit: Miss Foundation

Wolfelt shares his perspective, stating, “Many people have suggested that we have become more open in talking about death, grief, and mourning. I disagree and observe that we continue to be what I refer to as “mourning-avoidant” or “emotion-phobic” to a large extent. The majority of people in grief are still greeted with buck-up messages that invite them to leave their grief behind them as quickly as possible. We have short social norms for grief (the bulk of people get three days off work or school after a death, and it better be a biological nuclear family relative) and I continue to be asked on a regular basis, “How long does grief last?” That is like asking, “How high is up?”… In our culture we continue to de-ritualize around death with many people hosting parties instead of having meaningful funeral experiences. In many ways we have lost an understanding that there are times to have “proper sorrows of the soul.”

Growing Network of Grievers Supporting Grievers

Despite the general sense that society has a long way to go before being truly supportive of grief, there are growing opportunities for connection. After being widowed and feeling unsupported by many in her life, Megan Devine went on to create the website, “Refuge in Grief,” to support others who are grieving, and wrote an immensely popular book, “It’s OK to Not Be OK,” which became the best-selling book on grief in over a decade. In the book, she gives grievers permission to simply acknowledge their pain and connect with each other, writing: “The reality of grief is far different from what others see from the outside. There is pain in this world that you can’t be cheered out of. You don’t need solutions. You don’t need to move on from your grief. You need someone to see your grief, to acknowledge it. You need someone to hold your hands while you stand there in blinking horror, staring at the hole that was your life. Some things cannot be fixed. They can only be carried. Grief like yours, love like yours, can only be carried. Survival in grief, even eventually building a new life alongside grief, comes with the willingness to bear witness, both to yourself and to the others who find themselves inside this life they didn’t see coming. Together, we create real hope for ourselves, and for one another. We need each other to survive.”

There has been growing moment around creating spaces for grievers to connect with and support each other. In 2013, Gabrielle Birkner and Rebecca Soffer started the website Modern Loss, a website offering essays, articles, advice, and connection to other grievers. The space quickly became popular as one of the first online peer-to-peer communities for grievers, and caused the New York Times to reflect on how an online generation was redefining mourning through creating spaces online to acknowledge grief and offer peer support.

Lennon Flowers, co-founder and executive director of the Dinner Party that provides peer grief support for younger adults, shared similar experiences of the power of people naming when they were struggling and also finding support online. She reflected on how she has found that sharing grief in a supported group “can be some of the most generative material that we have for really deep connection.” The Dinner Party had initially involved sharing intimately over a common table of food, but when Covid-19 happened and quarantining restrictions limited online gatherings, they adapted to host Dinner Party tables online. Although initially hesitant over how it would be to connect via online platforms like Zoom, Flowers was pleasantly surprised at the depth of conversations that emerged. This move to online space also offered the added benefit of being able to offer affinity tables, or Dinner Party groups based on a particular shared experience or identity, that may have been hard to arrange in person.

Lennon Flowers, founder of The Dinner Party

Now that Covid-19 gathering restrictions have eased up, the Dinner Party offers both online and in-person gathering options, but Flowers continues to see a lasting impact from the pandemic. She believes that Covid-19 changed how open we are to holding space for grief and difficult emotions, describing, “It was a period of time that allowed us to say out loud, “I’m not OK,” and not break when we did it. Many people admitted that they were struggling and found that they did not break when they weren’t okay. It gave people permission to express vulnerability. Coming from an era in which culturally, we treated grief as though it was contagious, there was something powerful in naming and witnessing someone else’s grief and sharing your own. The experience of not being okay helped us develop a comfort level and normalization with it that also gave us tools to express grief. I won’t say that we’re wholly on the other side of being able to talk about grief, but I hope that is a lasting legacy from Covid.”

Informal studies from 2021 support Flowers’ observations about Covid-19 bringing grief to the forefront of people’s minds. Forty-seven percent of people in the U.K. reported feeling more compassionate to others dealing with grief, and 89% of American adults agreed that everyone should learn to talk about grief. Only 70% of those surveyed though, felt like they didn’t have the tools or skills they need to support someone who is grieving.

Clearly the pain of loss transcends time, and we continue to find new ways of naming, supporting, and living through grief. New communities and ways of coping continue to be explored, and people today seem to be more open to the idea that grief can be a fluid, individual process. There is no one right or wrong way to grieve. Although that statement may seem obvious to the readers of today, it would have been viewed as scandalous in the not-so-distant past. We continue to be impacted by historical grief theories and embrace parts of them, while also modern grief theories offer critique or new insights. But what really matters is if all this discourse around grief theory is actually helpful to grievers. One person may draw great comfort from the idea of grief being five easy stages to pass through, while others might appreciate Bonanno’s focus on resilience. Others find that looking for the continuing bond with their loved one brings them comfort, while others may eschew engaging in any theory and instead seek out support groups, online communities, or therapy to allow them spaces to talk about their grief. The most important grief theory is the one that provides support to each person as they navigate their own loss.

[1] Kübler-Ross E., Kessler D. (2005). On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief through the Five Stages of Loss. New York, NY: Scribner. Page 7.

Beyond the Five Stages: Grief Theories in the Modern Age

Beyond the Five Stages: Grief Theories in the Modern Age

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead