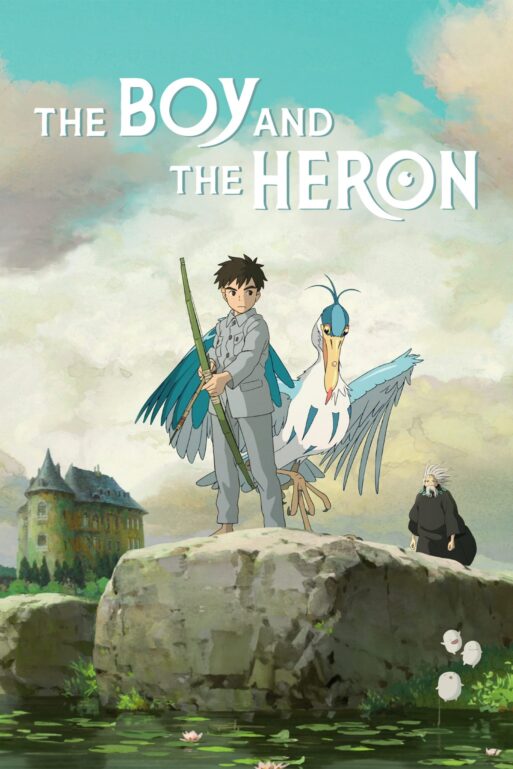

“The Boy and the Heron” is the most recent movie from Studio Ghibli and its legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. The works of Miyazaki are known for their whimsical storylines; beautiful, hand-drawn animation; and themes of environmentalism and pacifism. “The Boy and the Heron” continues in this vein, but also offers a fantastical exploration of grief through the protagonist’s journey.

“The Boy and the Heron” is the most recent movie from Studio Ghibli and its legendary filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. The works of Miyazaki are known for their whimsical storylines; beautiful, hand-drawn animation; and themes of environmentalism and pacifism. “The Boy and the Heron” continues in this vein, but also offers a fantastical exploration of grief through the protagonist’s journey.

“The Boy and the Heron” centers on a young boy named Mahito during World War II. Through flashbacks, we learn that his mother died in a fire at a hospital as bombs fell around them. The narrative starts in the aftermath, when Mahito moves to the countryside to join his father and soon-to-be stepmother Natsuko.

Mahito quickly encounters a mysterious heron who tells him that his mother is still alive and takes Mahito into a magical world of parakeet armies, underwater gatherings of shadow people, and his own Grand Uncle creating worlds out of stones from tombs. There are white blob-like spirits called the warawara who must ascend into the sky to get born as humans, but face being gobbled by pelicans. Initially furious at the pelicans, Mahito later learns that they were brought here against their will and are simply doing what they must to survive. Mahito eventually encounters a younger version of his mother, who tells him that she knowingly chooses to return to her future life where she gave birth to him, even though she must die. She refers to Natsuko as her sister and guides Mahito into a tower where Natsuko is about to give birth. Mahito realizes he must reconcile himself to the death of his mother and even in his grief, accept his new stepmother.

Mahito, the young protagonist of the film

Credit: gkids.com

The film manages to produce something mystifying and somewhat inscrutable, with so many layers upon layers of mythical beings or places that it starts to feel unmanageable to try and keep track of it all. Viewers who seek a straightforward movie plot would do well to avoid this esoteric film. But if you are willing to set aside the need for narrative logic, you may find that it enchants you.

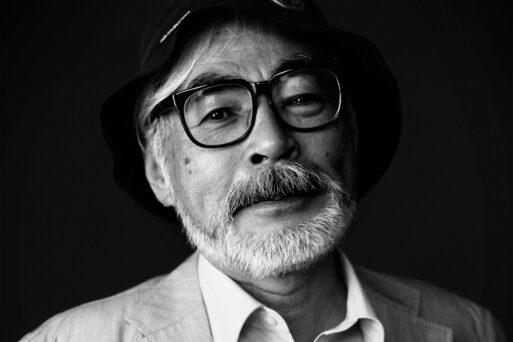

Watching the film is like being in a dream. Miyazaki’s imaginary world defies easy understanding, much like the process of grief itself, where small things take on outsized importance and tears flow at the most unexpected moments. The movie title in Japanese translates to “How Do You Live?” which points to the existential questions at the heart of the film – how do you live after loss, in a world that is both violent and beautiful? When asked by the New York Times about the answer to this, Miyazaki responded, “I am making this movie because I do not have the answer.”

Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary filmmaker behind “The Boy and the Heron”

Photo Credit: gkids.com

The presence of death weighs heavily throughout “The Boy and the Heron,” but the film is also deeply connected to life. The warawara either disappear into new life as humans or are sustenance for pelicans to continue their own life. Mahito finds a version of his mother but still must let her go and welcome a new family connection with Natsuko. Grief is present, but also an invitation to move forward. At one point, Mahito is given the opportunity to stay in his magical world and create it from scratch without any malice or return to his own flawed world. Mahito points to his own wounds and chooses to return to his world, having recognized that suffering is an inevitable, necessary part of life. For some grieving viewers, this film’s message may provide much needed solace, while others may be frustrated by its imaginative, inaccessible plot.

“The Boy and the Heron” by Hayao Miyazaki

“The Boy and the Heron” by Hayao Miyazaki

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”