Ramose served as the vizier and governor of the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes during its 18th Dynasty. Historians are almost certain that he and his wife, Meryet-ptah, left behind no heirs after he passed – but he did leave the legacy of an incredible, albeit unfinished, private tomb. Today, the famed paintings and reliefs of Ramose’s tomb allow historians to understand the ancient city’s culture, particularly on the subjects of death and the grieving process in ancient Egypt.

The construction of Ramose’s tomb began on the West Bank of Thebes during his lifetime, as was standard practice for important members of an Egyptian court. Despite his high rank and social connections, Ramose never quite finished construction of his tomb. The time Ramose served as governor spanned a transitory period between the reigns of Amenhotep III and IV – a reality that must have severely altered his construction plans. With the reign of different Pharaoh came a different capital, so Ramose began building his tomb, once again, at the new capital of Amarna.

With its T-shaped floor plan and detailed reliefs and paintings of the grieving process, Ramose’s tomb embodies many quintessential elements of ancient Theban tombs. A split stairway outside of the tomb brings visitors to its courtyard, which leads to an enormous, column-filled hall. As the tomb progresses, various reliefs begin to appear; in one, Ramose is at a funeral banquet surrounded by his family; at the turn of a corner one finds a painting of a lengthy funeral procession. The scene is one of splendor and wealth, with riches surrounding the deceased Ramose, whose servants remain ever-ready to serve him in the after-life.

“The scene is one of splendor and wealth, with riches surrounding the deceased Ramose, whose servants remain ever-ready to serve him in the after-life”

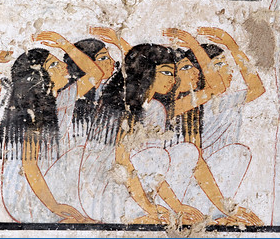

“Many scholars feel this particular scene represents one of the best pieces of ancient art to be found in the world,” stated Mark Andrews, in a documentary he directed on Theban tombs, “Every curl of a wig, bead of a necklace and soft fold of a garment is rendered in skilled detail.”

On another wall, mourning women are depicted in white robes and gathered close together, their hair loose as they take part in the funeral procession. On a wall further down, more women are depicted in instances of rather emotional grieving – they kneel on the ground while beating their chests and covering their heads in ashes.

Egyptian burial traditions have always been fascinating in their capacity to include intricate physical, spiritual and artistic practices. Some of the first accounts of embalming can be traced to the ancient Egyptians, while whispers of gold-laden tombs in the Valley of the Kings have become the stuff of legend.

Sadly, due to a bevy of political changes and construction issues, Ramose was never buried in his tomb. Nevertheless, it has preserved the memory of his life and legacy as governor of Thebes.

Related:

- Visit Ramose’s tomb in Egypt

- Explore Funerary Art from Africa and Egypt

- Read an Excerpt of “The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion”

Walk Like an Egyptian: The Art of Grieving in Ramose’s Tomb

Walk Like an Egyptian: The Art of Grieving in Ramose’s Tomb

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition