Though one of my favorite authors, Kurt Vonnegut is not the person I would turn to if I needed a burst of joyous inspiration, or even a lift after a bad day. After decades of story- and novel-writing on dystopian futures, devastating wars, and the sheer absurdity of human nature, Vonnegut earned a name for himself as one of the more cynical 20th-century American writers. He continued denouncing the foolishness of his fellow humans to the day he died in 2007 at the age of 84. Yet under the (admittedly thick) coat of pessimism, his works contained glimmers of hope and what was probably an abiding love for humanity—the good ones, anyway.

Though one of my favorite authors, Kurt Vonnegut is not the person I would turn to if I needed a burst of joyous inspiration, or even a lift after a bad day. After decades of story- and novel-writing on dystopian futures, devastating wars, and the sheer absurdity of human nature, Vonnegut earned a name for himself as one of the more cynical 20th-century American writers. He continued denouncing the foolishness of his fellow humans to the day he died in 2007 at the age of 84. Yet under the (admittedly thick) coat of pessimism, his works contained glimmers of hope and what was probably an abiding love for humanity—the good ones, anyway.

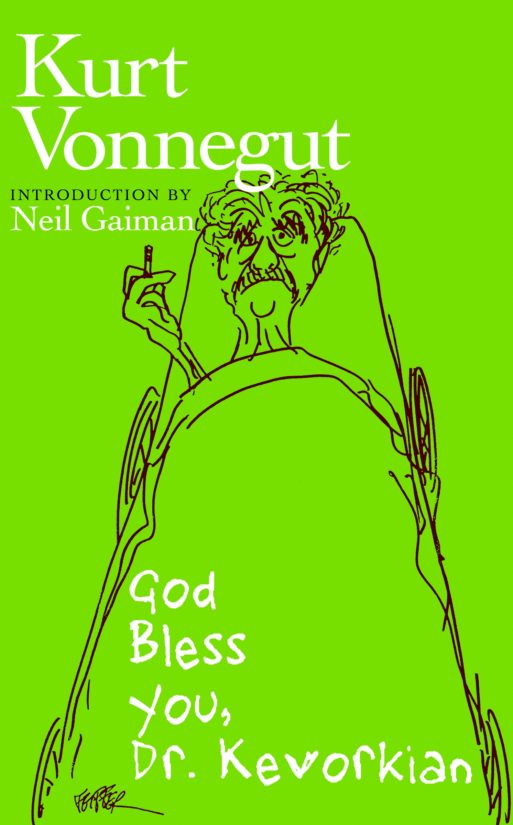

In God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, a short collection of fictional interviews in novella form, Vonnegut’s signature mix of cynicism, humor, and moralizing is on display. Written in 1999 and using the recent controversy surrounding Dr. Jack Kevorkian—aka “Dr. Death” —as a jumping-off point, Vonnegut claims to have engaged in a series of “near-death experiences” by using Kevorkian’s assisted suicide machine to go down the blue tunnel to Heaven and converse with many famous and interesting people on the other side.

The famous people include John Brown (of raiding on Harper’s Ferry fame), Sir Isaac Newton, Clarence Darrow, and William Shakespeare (who hates Vonnegut’s writing and yells at him, “Get thee to a nunnery!”). But the random stories of everyday people who have passed on are far more interesting.

Vonnegut meets Dr. Mary D. Ainsworth, a developmental psychologist who died the previous March. She is excited to discover what happens to babies in heaven. “It turns out there are nurseries and nursery schools and kindergartens in Heaven for people who died when they were babies. Volunteer surrogate mothers, or sometimes the babies’ actual mothers, bond like crazy with the little souls.” Then they become angels.

He meets Roberta Burke, who during life was the wife of a navy admiral named Arly. They met on a blind date in 1919, when Roberta was a last-minute substitute for her sister Faye, and were married for seventy-two years. “The simple epitaph Roberta Gorsuch Burke chose for her tombstone here on Earth: ‘A Sailor’s Wife.’”

He meets Peter Pellegrino, an avid balloonist and founder of the Balloon Federation of America in life. When Pellegrino hears that Vonnegut has never ridden in a balloon, he says, “‘For God’s sake, man—get a tank of propane and a balloon while you’ve still got time, or you’ll never know what Heaven is!’ Saint Peter protested. ‘Mr. Pellegrino,’ he said, ‘this is Heaven!’ ‘The only reason you can say that,’ said Pellegrino, ‘is because you’ve never crossed the Alps in a hot air balloon!’”

Vonnegut himself did not believe in heaven: he was a secular humanist and a member of the American Humanist Association. So the extent to which this exercise in heaven-imagining should be taken seriously is really up to the individual reader. Yet despite the setting of most of the book, the stories are less about death, and the afterlife, than they are about life. It examines, in Vonnegut’s characteristically succinct way, what people live for and what people live by. It imagines what it would be like after, whether or not there is a heaven—what endures beyond a single person’s lifetime: what they loved, what they stood for, what they believed in. What remains when the person’s time on Earth has gone?

At the very end, on his last “controlled near-death experience” with Dr. Kevorkian, Vonnegut meets Isaac Asimov, his predecessor in real life as honorary president of the American Humanist Association. He notes Asimov’s prolific writing during life, and asks him if he is still writing now that he is in Heaven. “All the time!” Asimov replies. “If I couldn’t write all the time, this would be hell for me. Earth would have been a hell for me if I couldn’t write all the time. Hell itself would be bearable for me, as long as I could write all the time.” “Thank goodness there is no Hell,” is Vonnegut’s dry reply.

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian by Kurt Vonnegut

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian by Kurt Vonnegut

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull