Steven Spielberg’s latest film, Lincoln, begins on a mud-soaked, blood-soaked battlefield that recalls the opening to Saving Private Ryan, except with bayonets and 19th-century marching squad uniforms instead of bullets and flak helmets. At the battle’s conclusion, the victorious soldiers, a squad of black soldiers fighting on the Union side, briefly discuss the politics of the day (Lincoln’s battles in Washington), with a white commander from a different detachment. The commander admits that, while their comrades fought and died bravely, awarding them the requisite commendations and promotions as they would a white person is not yet in the cards. The injustice of this interplay serves as a perfect introduction to the core of the film’s real battlefield, that is, the legislative floor. From there on out, Lincoln becomes a political drama, a sort of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington meets Amistad, except that, perhaps unexpectedly, that very process of vote-buying and bill-writing, so universally disdained these days, is endowed with a grandeur and suspense that many voters might find tiringly unfamiliar.

Steven Spielberg’s latest film, Lincoln, begins on a mud-soaked, blood-soaked battlefield that recalls the opening to Saving Private Ryan, except with bayonets and 19th-century marching squad uniforms instead of bullets and flak helmets. At the battle’s conclusion, the victorious soldiers, a squad of black soldiers fighting on the Union side, briefly discuss the politics of the day (Lincoln’s battles in Washington), with a white commander from a different detachment. The commander admits that, while their comrades fought and died bravely, awarding them the requisite commendations and promotions as they would a white person is not yet in the cards. The injustice of this interplay serves as a perfect introduction to the core of the film’s real battlefield, that is, the legislative floor. From there on out, Lincoln becomes a political drama, a sort of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington meets Amistad, except that, perhaps unexpectedly, that very process of vote-buying and bill-writing, so universally disdained these days, is endowed with a grandeur and suspense that many voters might find tiringly unfamiliar.

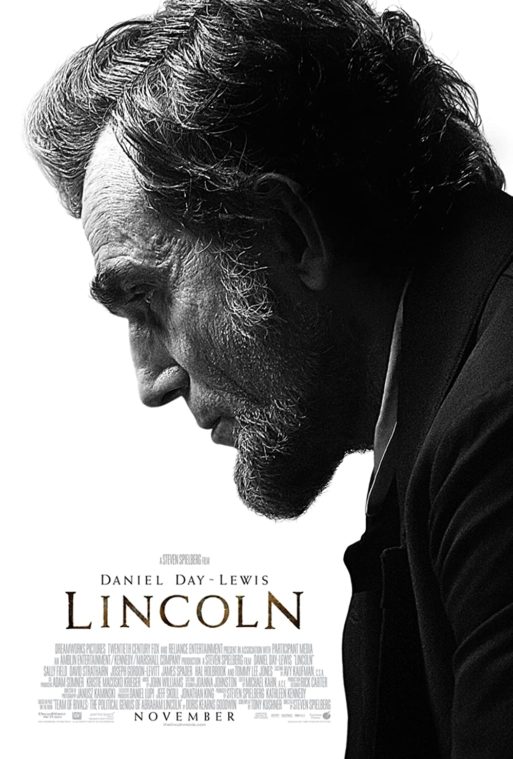

It might be due to the heavy-hitting cast, including Daniel Day-Lewis in the title role, Tommy Lee Jones as Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, his stalwart abolitionist ally, or any number of the other character actors who make their appearance (whose number is in fact so many that the likes of Adrian Brody go by practically unnoticed); or it could be the cinematography, the staging and setting so vividly brought to life; or it could yet still be the writing, the dialogue, which brings out the humanity of the legislators even while they are legislating. We are reminded that the passage of the 13th Amendment, to be followed by the 14th and 15th, which, as a trio, greatly expanded Americans’ civil rights, was not a foregone conclusion. Had we been cursed with a less skilled gamer and negotiator than (sometimes-not-so) Honest Abe, American history could have gone a far more tortuous route than it did. The war could have dragged on, or it could have been given a second wind later. At the film’s climactic scene, when the actual voting is taking place, and the congressmen are choosing their sides, the suspense is real indeed.

Says The New York Times’ A.O. Scott, “To say that this is among the finest films ever made about American politics may be to congratulate it for clearing a fairly low bar.” Still, it is a bar that Spielberg might have vaulted with aplomb. The viewer can feel the weight of history throughout, and the film’s length detracts nothing. When the final shot does come, Spielberg has us in a theater, but not the theater where Lincoln dies. Instead, a caller interrupts the performance to give the audience the news, and allow us witness to their reaction. This, perhaps, was an even more powerful choice, because it wasn’t so much the death of Lincoln, the man, that struck us all so powerfully, it was the random assassination of perhaps our greatest president, at least our most historically accomplished. This is an important distinction. It is the truth of history that matters, after all, and we can give many thanks to Spielberg for creating so stirring an account of it.

- Here is a review of one of last year’s very different Oscar contenders, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011).

- Read about the aid-in-dying controversy as it relates to the political culture wars.

“Lincoln” (2012) by Steven Spielberg

“Lincoln” (2012) by Steven Spielberg

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls