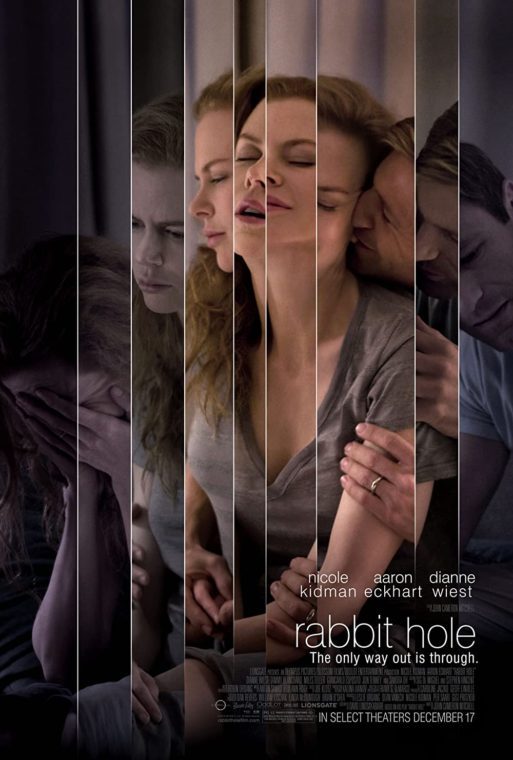

“Rabbit Hole” is a 2010 film based on the play of the same name by David Lindsay-Abaire. The story follows a young couple struggling to live with their grief after a car hits and kills their son four-year-old son, Danny. Director John Cameron Mitchell takes an honest look at the path of grief in “Rabbit Hole,” focusing on how it pervades a couple and entire family’s dynamic.

“Rabbit Hole” is a 2010 film based on the play of the same name by David Lindsay-Abaire. The story follows a young couple struggling to live with their grief after a car hits and kills their son four-year-old son, Danny. Director John Cameron Mitchell takes an honest look at the path of grief in “Rabbit Hole,” focusing on how it pervades a couple and entire family’s dynamic.

Danny’s death happens eight months before the time at the start of the the film, but the weight of its grief – the responsibility his parents feel to carry it while living everyday lives despite their depression – is ever-present. The film focuses on how couple Becca (Nicole Kidman) and Howie (Aaron Eckhart) struggle to accept how the world goes on. Life continues, whether we want it to or not.

“Rabbit Hole” looks at life after grief through this lens. It isn’t a film that indulges in the horrific moments directly proceeding a death, in typical Hollywood fashion. It isn’t a movie that ties itself up in a bow, giving us a snapshot of a happy couple after the initial years of their grief. No, Mitchell’s lens stays on the present, awkward period of grief: a time when the wound is not quite fresh, but hasn’t yet healed. He lives in what you could call, “the grief in between.”

“Mitchell’s lens stays on the present, awkward period of grief”

Throughout the film, Becca and Howie struggle to point fingers for a loss that was simply a tragic accident. The car wasn’t driving too fast, nor was the teenager behind the wheel distracted or drunk. Where can the couple direct their anger when there’s no one to blame? How many times can they play over the events preceding Danny’s death? The two were living a relatively privileged, rosy life beforehand: solid jobs, a lakeside house with a picket fence. But all of that changed when Danny died. They never make love, never make plans with friends and become distanced by their different grieving patterns. Becca chooses to take down all of Danny’s drawings from the fridge and give his lunchbox to Goodwill. In the meantime, Howie sneaks down to their living room at night and watches videos of Danny on his phone. It seems as though the two are just strangers living under the same roof. Their days are spent in what feels like a surreal, dishonest routine as Becca gardens, bakes, and runs on her treadmill, or as Howie heads out to play tennis.

“Their days are spent in what feels like a surreal, dis-honest routine …”

The film’s opening sequence is a perfect example of how we can hide away our grief in the ritual of our emerging “normal” life. The scene shows Becca planting flowers in her garden, but with such precision and tenderness that we know she’s compensating for something.

A neighbor pops by to ask if she and Howie would like to come over dinner. She says no, thank you, and wears her excuses and composure well enough – but her pleasantry breaks when the neighbor accidentally steps on a flower on her way out.

Suddenly, in a row of ostensibly perfect and unmarred violets, Becca must address the fact that one of her buds is broken.

“Rabbit Hole” wouldn’t be possible without the finesse of Mitchell’s directing, or without Kidman’s on-point acting skills. Sitting in such unwavering, quotidian grief would be too much for 90 minutes. But Mitchell’s camera is so detail-orientated that it finds not only the sharpest points of grief following a sudden death, but the moments where peace and humor appear in its midst, however fleeting such moments may feel – which is just Mitchell’s point: grief never ends, but it won’t eclipse your world forever.

Watch the trailer for “Rabbit Hole” below:

Your may enjoy:

- Making Sense of A Senseless Loss: The story of a woman’s healing process after her 21-year-old son was murdered

- How to Deal with the Loss of a Child? An Interview with Henry Allen

- Reflections on the song “Baby Mine” by Bette Midler.

“Rabbit Hole” (2010) by John Cameron Mitchell

“Rabbit Hole” (2010) by John Cameron Mitchell

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition