A prominent 20th-century author and one of the great masters of language, Vladimir Nabokov wrote his share of epic, seminal novel-length works, including Lolita, Pale Fire, and Ada, or Ardor. But in the short story “Breaking the News,” first published in a Russian periodical in 1935, all of his powers of narrative and emotion are encapsulated in just a few short pages about a woman who, in a room full of people, is the only one who doesn’t know she’s lost someone.

A prominent 20th-century author and one of the great masters of language, Vladimir Nabokov wrote his share of epic, seminal novel-length works, including Lolita, Pale Fire, and Ada, or Ardor. But in the short story “Breaking the News,” first published in a Russian periodical in 1935, all of his powers of narrative and emotion are encapsulated in just a few short pages about a woman who, in a room full of people, is the only one who doesn’t know she’s lost someone.

The story begins with this blunt, straightforward paragraph:

“Eugenia Isakovna Mints was an elderly émigré widow, who always wore black. Her only son had died on the previous day. She had not yet been told.”

On the morning in question, in her apartment in Berlin, she receives a letter from her deceased son, who unbeknownst to her had the day before fallen down an elevator shaft at the factory he worked at in Paris, and not survived. Meanwhile, family friends had received a telegram notification of his death that same morning; “in consequence of which the lines (virtually inexistent) that [Eugenia] now read, standing with the coffeepot in one hand, on the threshold of her sizable but inept room, could have been compared by an objective observer to the still visible beams of an already extinguished star.”

Significantly, Eugenia is deaf, or mostly-deaf. She carries around a hearing aid, which she switches off whenever she no longer wishes to speak to someone. We see her taking a walk through the rain, hearing aid off, going about her business, shopping; deaf to the world around her and somehow isolated from the reality that exists just outside of her realm of consciousness, including what has happened in Paris.

We see the family friends agonize over how to break the news. It’s a terrible task, and all are hesitant. The only one who seems sure of what to do is a female lodger who is staying with them; detached as she is from the characters in this situation, she objectively advises them to break it when they are ready, as it won’t make much difference. She chastises Mr. Chernobylski for feeling guilt over the fact that he was the one who procured the job for Eugenia’s son in Paris. “Who could foresee? What have you to do with it?” she scolds, ignoring the fact that guilt and grief don’t always have to be rational.

At the end, the friends gather in Eugenia’s small apartment, none of them having yet broken the news. Eugenia is thrilled to have so many visitors and bustles about, fetching refreshments. However, as she is forced to sit down on the couch by her distraught friends, she slowly realizes that something isn’t right. She finally turns on her hearing device and frantically begins to point it around, hoping someone will reveal the truth to her. Finally, the not-knowing is worse than the knowing.

The doorbell rang, and the solemn landlady, in her best dress, let in Ida and Ida’s sister: their awful white faces expressed a kind of concentrated avidity.”She doesn’t know yet,” Chernobylski told them; he undid all three buttons of his jacket and immediately buttoned it up again.

It’s a heartbreaking little vignette. In a way, it represents that strange, limbo-like space between the Event—the son’s death—and knowledge of the Event, between the loss and the grief of the loss. As we observe Eugenia, we are privy to the full situation, and she is not.

It also is an illustrative example of the ways in which people fear to discuss death, to be the bearer of bad news. It was almost as if, by leaving it unsaid, they could spare Eugenia from ever having it actually happen. Of course, this is an unsustainable situation, and by the end of the story we see it fall apart.

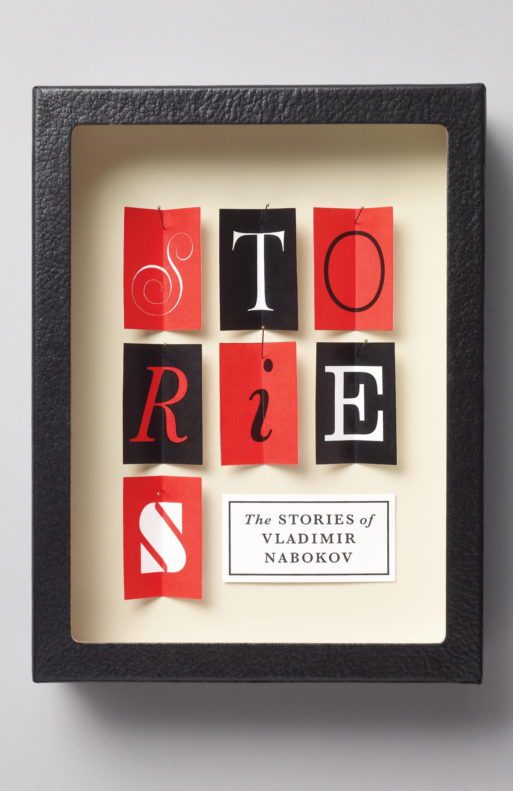

This story, and many other equally lovely and poignant ones, can be found in the collection The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov.

Short Story: “Breaking the News,” by Vladimir Nabokov (1935)

Short Story: “Breaking the News,” by Vladimir Nabokov (1935)

Who Cares for the Caregivers?

Who Cares for the Caregivers?

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying