This is the story of Bobby as told by his son, Neal. Our “Opening Our Hearts” stories are based on people’s real-life experiences. By sharing these experiences publicly, we hope to help our readers feel less alone in their grief and, ultimately, to aid them in their healing process. In this post, Neal tells the story of his father and his death from skin cancer. This is an open and honest recalling of a loving but troubled relationship that ended in death without resolution, and the brand of emptiness a loss like this can leave in its wake.

It was my birthday, 2012. My phone rang and I saw it was my sister. I was delighted; a happy birthday wish from anyone back home was welcome. But it turned out my birthday wasn’t a topic of conversation — my father had recently undergone a gall bladder procedure, after which his surgeon recommended he see an oncologist immediately. The verdict was stage 4 melanoma, metastatic. My father’s body was riddled with cancer, and I was 3,000 miles away, actively running from the dysfunction and depression that were hallmarks of home for me. I packed my car with all I could carry and abandoned my life in California to be with my family while the death of my father played out.

I had moved my life to California less than a year previously, mostly to put as much distance as possible between myself and my hometown. It’s a place that always seemed to offer me more opportunities for failure than success, and as a child, I’d gone blindly down all the wrong roads without what I consider proper guidance and discipline. I went from an honor student to a high school dropout in less than a year – all while my parents stood idly by and let me take one wrong turn after another. I ended up in prison for a drug crime. And while my family was always there during those years, when it was over he never let me forget the “debt” I owed him and all the rest for standing by me in my time of need. He never forgave me for going to California and made sure to remind me that it was wrong to put my own interests first whenever he had the opportunity.

How could they know that I would never be fulfilled by the kinds of work that had allowed them to raise a family?

Looking back, I think it was my parents who owed me a debt they could never pay. They did the best they could, but they still failed me – how could people who spent their childhoods picking cotton possibly understand the importance of nurturing a child with intellectual gifts like mine? How could they know that I would never be fulfilled by the kinds of work that had allowed them to raise a family? They had no knowledge of the world of ideas, and they simply didn’t know how to recognize or respond to the cues we were given that my life should be about something more than food and shelter.

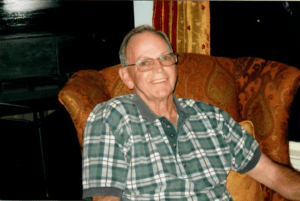

My father was a good man. He’d been born the son of North Carolina sharecroppers in 1938, and in the aftermath of WWII, he took advantage of the booming, mid-century American dream to raise a family and bring us out of a legacy of poverty. We became a solidly lower-middle-class family from his efforts alone – not bad for someone with a sixth-grade education. But cancer has no regard for virtue or kindness or hard work or anything, good or bad. Cancer speaks the brutal language of nature—a language of living and dying, and not much else.

Dad had a hard time accepting the language of death. His revolt began before I even made it home. My first clue was a phone call:

“Hello.”

“Hey Neal, it’s your dad.”

“Hey Dad, what’s up?”

“Where are you?”

“I’m in Texas. I stopped to visit a friend in Dallas and stayed an extra day.”

“You need to be on the road and headed straight home. You have a duty to be here now. You should be here by now.”

“I took a detour to spend a night in Death Valley. I wanted to see the stars since I was camping anyway. When I leave here, I’ll be home in two days.”

“Well hurry up. This isn’t the time for you to be on one of your road trips.”

Maybe he was right. Maybe the situation was more urgent than my response, but I knew the coming months would be tough, and I was less than enthusiastic about going home. The guilt seed was sprouted, rightly or not, and there would be plenty of room to grow back in Carolina.

Cancer speaks the brutal language of nature—a language of living and dying, and not much else.

The next few weeks involved some time in doctors’ offices. One oncologist, in particular, the first one we saw, had the bedside manner of a ditch digger. He offered no hope outside of a prescription for an experimental drug that “could potentially slow the progress of the cancer” at a cost of over $11,000 per month, and promptly left the room when a nurse came and announced he had a phone call. This three-minute exchange had a multiplying effect on all the negative emotions that came with cancer. We eventually found better care, but this interaction was powerful and its effects lasting for me. This man couldn’t have cared less.

For my part, I was angry: angry at having to leave my life behind, angry that a thing like cancer compelled me to be home in North Carolina, angry at the doctor and his nurse, and angry at my father, who was also angry.

He was angry about dying and having no control, I think. We never talked about it, but that’s my best guess. Whatever it was, it changed him for good. He yelled about my sisters and how they weren’t doing enough. He yelled at my mother and me. At one point I was so fed up with how he was treating people that I threatened to go back to California and leave him to die without me. Neither of us was at our best, and I don’t think I was any closer to mine than he was his. He died too soon for either of us to get past the anger.

At one point I drove him the 50 miles to the research hospital that was treating him, supposedly for just a “routine” visit, but nothing is routine when cancer comes calling. They said they’d have to admit him for observation, and that’s when it finally sank in that he was really and truly dying. I thought he would die in that room, which I knew would be fundamentally wrong — he had chosen to die at home, and I didn’t want him to be on the wrong side of a horrible statistic. Luckily, he made it out of that hospital room alive.

“Please don’t go back to California. I love you, and I’m sorry I said those things.”

In the weeks following, the man I knew disappeared. Maybe it was the heavy drugs, maybe it was cancer eating his brain, but my father was gone. He would wail at night from his bed. Eventually, I moved to a tent in the backyard to escape what sounded like tortured insanity to me. In the mornings he would tell me about the people in his room at night, and how they did things like paint his ceiling while we all slept. It was obvious to him. Couldn’t I see the paint with my own eyes? In the midst of all this, he had moments of lucidity that I was never prepared for. A couple of weeks before he died, just prior to losing his capacity to communicate, he said to me, “Please don’t go back to California. I love you and I’m sorry I said those things.” I had no fitting reply, and I was almost blinded by the pleading in his eyes. I think a hug was all I could muster. Those were among the last meaningful words he said to me.

He died quietly about midnight on a Tuesday.

I still think I blew it. No matter what I tried, I could never shake the feeling his cancer was a burden I just didn’t want to bear. I was bitter because of this, and I never cried a single tear that wasn’t at least partially for me. There wasn’t a single happy moment from the day I got the call until the day I was finally able to leave Carolina, and all I felt was relief at his passing. Even at the moment, I realized he was gone, my mind turned back to my own life and how to get back to living it.

Others say I was a good son for just being there, but I’m not sure I agree. We’d had an up-and-down relationship for decades, and it was partially resentment toward him that caused me to flee 3,000 miles in the first place. I do miss him, but I don’t miss the guilt he unloaded on me, and I’ve spent much of my life since his death slowly forgetting the bad stuff. The sad truth is – and I’ll leave it right here – as years go by and I let go of my guilt and resentment, less of my father remains. Where fond memories should live, I often find only empty space.

Carolina Blue: How Cancer Killed My Father and Our Already Failing Relationship

Carolina Blue: How Cancer Killed My Father and Our Already Failing Relationship

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition