Consider the relationship when choosing to deliver the news that someone has died in person, on the phone, by email or over social media.

“Where were you when you learned Princess Diana had died?” This seemingly innocuous question, common among those who were highschool-aged or older when the British royal princess died in 1997, points to something significant: When, and how, we break the news that someone has died matters.

To a certain extent, we all know this. Yet few individuals, when confronted with the death of a loved one – whether in a tragic accident, due to a sudden health failure, or following an extended illness – are prepared to inform others of the death. This is hardly a surprise, considering our societal denial of death. Yet the inability to share the news that someone has died in a sensitive manner has consequences: It can cause unnecessary pain and sorrow; create rifts rather than connection at a time when connection is crucial; and add to the burden already placed on grieving relatives.

SevenPonds Founder Suzette Sherman experienced the fallout of poor delivery firsthand when informed of the death of an old, dear friend. Sherman had met Pamela when they were coworkers in the same Manhattan office in the 1980s. The two women immediately hit it off, sharing regular outings and long phone conversations. They lost touch after Sherman moved to the Bay Area in 2001, so when Sherman ran into a close friend of Pamela’s, who’d also moved to the Bay Area to work at a tech company, and learned that Pamela had ALS, she resolved to get in touch. But life was busy – and Pamela died. Sherman found out after emailing their mutual contact a Google Doc outlining information about a house she planned to purchase; the woman responded to the Google Doc with the news. Because there was no separate email or subject heading, and Google Docs rarely require such responses, Sherman missed the news for more than a week before opening the email as a fluke. “I was devastated,” Sherman said. “I was utterly stunned by the fact that she did it in a way that was so inconsiderate – even, I think, of Pam.”

For many, receiving or waiting for bad news can be just as complicated as delivering it. When Jennel McDonald’s father, Wayne, died in 2014 at the age of 78, her brother called to inform her that something had happened, and that it was possible he’d died. Seeking comfort as she waited for further information, McDonald called her aunt (on her mother’s side), who reassured her that her father would be fine. This turned out not to be true. “I was calling her because both of my parents were unavailable and I needed someone at that time to care for me,” McDonald said. “And she did her best, she did what she thought she should do…. What would have been better would be for her to say, ‘Well, Michael’s going to find out, he’s going to call you, and do you want me to stay on the phone with you until he does?’”

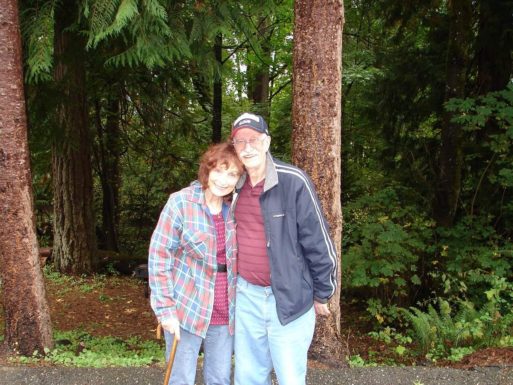

Jennel McDonald’s parents, Wayne and Valerie McDonald

Credit: Courtesy of Jennel McDonald

After her father’s death, McDonald found herself informing others, in addition to obtaining death certificates, planning the funeral and handling other business-related matters. While she considered it appropriate for her and her brother to call her father’s siblings, McDonald said that an aunt took over calling distant relatives, and it would have been helpful for others to step in, as well. “The more you can take off a person’s plate, the better,” she said. Rather than facing the vague question, “What can I do?” (when already overwhelmed), McDonald would have appreciated friends and relatives offering to call people, or to perform other specific tasks. “I had to hold my grief to the side because everyone else was pouring their grief on me,” she said. “It would have been nice for someone else to have taken that over.”

Tips for Breaking Bad News

Sherry Cormier, a licensed psychologist and certified bereavement trauma specialist in Annapolis, Maryland, said that when grief-stricken individuals are required to break bad news to others, it’s especially important they take time to prepare themselves. “Before you get on that Zoom call or that FaceTime call, I would recommend that you just really sit with yourself for a minute, and breathe, and try to work with your own emotions first,” she said.

Sherry Cormier on a outdoor stroll

Cormier, who explored the loss of her husband, father, mother, and only sibling in her book, “Sweet Sorrow: Finding Enduring Wholeness After Loss and Grief,” recommends that people be told in person, if possible, and if not, over video chat so that “you still have that personal connection.” She also recommends that people keep the information short, stick to the facts, and be truthful. “Be very direct – do not beat around the bush, which is easy to do when we’re uncomfortable,” Cormier said. “I would likely say something like: ‘Jane, I’ve got some really hard news to tell you and I’m really sorry. I want to let you know that Mom had a sudden heart attack this morning. The EMS came, and they couldn’t bring her back, and she died on the living room floor. And I know this is really hard.’” Cormier then recommends stopping and giving the recipient time to breathe, take in the information, react or ask questions.

Experts agree that it’s important to preface bad news with a warning statement. Kenneth Doka, professor emeritus at the Graduate School of The College of New Rochelle and senior vice president for grief programs for the Hospice Foundation of America, said it’s important “to maintain a somber note, to give some sort of a verbal warning, and if there’s history, to draw on that history.” For example, he said, you could use the phrasing: “I’ve got some bad news for you. You know that Grandma has been sick for a long time, and this morning we heard that she finally died.” For sudden events, he said, the news can be prefaced with a statement such as “We were totally surprised to find out that….” Doka added that it’s best to make sure that “anyone who’s a stakeholder,” such as close family and friends, is informed before the news is posted on social media.

Kenneth Doka, who coined the term “disenfranchised grief“

While news that someone has died is ideally shared in person, friends and family members outside the inner circle can be called or emailed, while those further afield may learn about the death through social media or word-of-mouth. Nevertheless, close relatives living at a distance – not an uncommon occurrence in today’s globalized world – must also be informed by phone or video chat. Grief Recovery Specialist Lisa Athan, who has a master’s in counseling and serves as executive director of Grief Speaks, once worked with a father whose son died tragically while in college. He ended up calling his daughter, who was also at college, and informing her over the phone. ”For one hour his daughter wailed, cried, couldn’t breathe, and then would catch a breath,” Athan said. After about an hour, she thanked her father for being there and stated that she’d never felt as close to him as she did in that moment. While the father didn’t feel like he’d done anything, Athan said, “he did so much: he created that safe space so she could just express in whatever way she needed to express.”

________________________________________________

What to Do:

• Warn people that you have bad news to share

• Be as truthful as possible

• Expect a range of responses

• Allow space for silence and questions

• Explain the basics to young children

• Use compassion for those with dementia

• Ask for help in breaking bad news, or offer to help others

• Carefully consider and individually tailor your delivery method

________________________________________________

Both Athan and Cormier emphasized that it’s essential to be as honest as possible – even when dealing with homicide, suicide and overdose deaths. “I would keep it short, initially, and truthful,” Cormier said, adding that while details can be withheld, some people may ask for them. People known as “sensitizers” prefer to know details, while others, called “repressors,” find that too much information freaks them out, she said. “You have to sort of take your cues from the person you’re giving the news to. Do they keep pressing you for details, or do they want to shut it down and get away from the conversation?”

The person breaking bad news can face a multitude of different reactions from adults, all of whom grieve differently. Athan said that intuitive grievers may cry openly, join a support group, or talk about their loss; cognitive grievers process things more privately or internally, and may cry in the shower; while instrumental grievers put their grief into their career, or into starting a scholarship. Some grief-stricken individuals will express anger. “We all might do a little of each,” Athan said. “But I think when an adult cherishes another adult and they have a different style, they can surprise the person giving the message.”

Cognitive and Developmental Considerations

When sharing news that someone has died with children, or elders with dementia, it’s important to take their developmental ages and cognitive abilities into account. Athan, who has often worked with families breaking bad news to children, said that ideally a loved and trusted adult will share the news in a safe environment, and in a way that isn’t rushed. With children, she said, it can be even more important to avoid euphemisms, which may limit understanding, and to engage in truth-telling. Once, an 8-year-old child told Athan that his father had died “because his brain didn’t work well,” an explanation that could as easily refer to suicide as to a brain aneurysm, but wouldn’t leave him wondering why explanations weren’t adding up, or whether he was at fault – a common misconception among children. In addition, Athan has found it helpful to ask children how much they know – that their mother has been sick, for example – before explaining what happened in language they can understand. For very young children, this may include phrases such as “they were very, very sick” (to differentiate the situation from common illness); “the doctors and nurses tried to help them”; or “their body stopped working.”

Beverung poses with her daughter

Lauren Beverung, an assistant professor of psychology at the Milwaukee School of Engineering explained that “before ages 6, 7 and 8 children don’t have a full understanding of what death means. So children may think that it’s reversible, or they may not understand that a dead body no longer works, that it doesn’t need to eat or breathe, or that they can’t feel uncomfortable.” Beverung recommends preparing young children for the conversation by saying: “I need to talk to you about something that is very important. It might make you feel sad, and you might have questions, and I’m here with you to answer those questions.” While it’s a good idea to give young children space to express their feelings, ask questions or react, Beverung emphasized that the most important thing is to assure them that they’re safe. “That’s going to be their first concern,” she said. “Is this going to happen to me? Did I cause it? Am I going to die? Are you going to die?” Beverung said it’s important to make death and grief an open topic, and encouraged giving children roles in funeral preparations – young children could look through photos for a picture board, or draw a picture to place in a casket, she said; older children could serve as a pallbearer, or speak. “There are a lot of different ways to help them work through their grief,” Beverung said.

While young children often struggle with comprehending death, elders with advanced dementia face a different challenge: they can’t always remember that a death has happened. When this occurs – particularly when it’s a spouse, or another close relative – they can face devastating news on a repeated basis, a particularly cruel turn of events. “We don’t want to see them suffer repeatedly over what they think is brand new information,” said Carol Bradley Bursack, a consultant, columnist, and author of “Minding Our Elders: Caregivers Share Their Personal Stories,” who has spent two decades caring for seven elders, including her parents. “Common sense works into this – where is the person cognitively, and what can they retain? And compassion works into it, too.”

Carol Bradley Bursack

While Bradley Bursack advocates honesty – she believes everyone, no matter what their abilities, should be informed at least once of a loved one’s death – she also believes that there in times when “fiblits,” or white lies, are warranted. “I don’t like to look at it as lying, because I don’t think it is,” she said. “I think it’s compassion. What we’re doing is, we’re getting into their world, where they are mentally, the best that we can.” When her father suddenly came down with dementia following a surgery to relieve fluid in his brain, Bradley Bursack intuitively recognized that she needed to meet him where he was – an approach now considered common practice. At the time, caregivers typically used “reorienting” efforts in an attempt to bring dementia sufferers back to reality – but for many, this only caused more distress. “That’s what you would be trying to do if every time they asked about this person that they cared about – their mate, especially – and you told them: ‘They died,’” Bradley Bursack said. “They can’t grasp reality because their memory will not hold the information in order to have them grieve properly.” Instead, Bradley Bursack advocates using phrases such as “He can’t be here right now, but you’ll see him later” – which may, depending on one’s belief in the afterlife, have some truth to them.”That would be my approach,” she said.

Grief is an Ongoing Process

Most people, fortunately, can retain news of a death and enter the grieving process. Regardless, sharing the news that someone has died is rarely “one big tell-all” – especially for children, Athan said. When listening to a podcast, she heard a hospice nurse compare the manner in which children process grief to the way they eat an apple – they take a bite, leave it, and come back. Children will often return for details – sometimes, years later – and may not initially understand that they’ll never see the person again. Adults also take time to process the news, and can come back for more information. Athan had trouble accepting her own mother’s death despite the fact that it was expected. “We know in our head, but not in our heart,” she said. “That shift from the head to the heart takes a long time.”

Grief Recovery Specialist Lisa Athan

Families often ask Athan if it’s okay to cry when they share news of a death with children. “That’s okay, that’s actually good – you’re modeling grief,” she said. “Kids aren’t born scared of death and grief. They take our cues.” (Situations that may be problematic, she said, are those in which a parent is hysterical or overwhelmed by grief, which is likely to frighten children or make them feel unsafe.) Athan recommends making use of age-appropriate books and other media – such Sesame Street, “My Uncle Keith Died,” “The Invisible String,” or “When Dinosaurs Die” – as well as finding local grief support and resources through organizations such as the Dougy Center. Kids “don’t necessarily need therapy, even if a parent died,” she said. “They need support; they need to know that it’s okay to feel how they feel; they need people that see them. And they need ways to express their feelings.”

________________________________________________

What Not to Do:

• Jump straight into shocking news

• Tell lies in an attempt to assuage someone’s pain

• Delay breaking bad news by engaging in unrelated conversation

• Use euphemisms for death such as “passed” or “left this world”

• Give too many details in the initial conversation

• Expect it to be a “one-and-done,” especially with children

• Use social media until close friends and relatives have been notified

• Assume you know how close the relationship might be

________________________________________________

Adults do, too. Often, Cormier said, the person receiving the bad news will attach to the person who delivered it, and may require some follow-up. “When people start grieving they’re going to start feeling very alone and isolated,” she said. “They’re going to form a link to you because you gave them the news even if you’re not part of the family, and they would really benefit from you staying the course – not just giving the news and then leaving right away. So prepare to be with that person for a while, in person or on the phone, and then make sure to follow up.”

For those seeking more information, or an ongoing shoulder to lean on, however, McDonald recommends careful consideration of where one goes for such support. When her mother Valerie died 6 years after her father, in 2020, McDonald found that some of her mother’s friends, and even care home workers, reached out to her for comfort, or a sense of absolution – obligating McDonald to console them when she herself was grieving. “You have to think real hard about who it is you’re going to put in that position, and the timing of it all,” she said.

The responses McDonald appreciated most were the people who, upon hearing the news, shared positive stories or memories of her parents, or acknowledged the impact they’d had on others’ lives. “‘I’m sorry for your loss’ is a very lonely statement,” she said. “But when they share it – when they’re like ‘What a giant of a man, I’m so sorry that we lost him,’ and then share something that they were touched by – I think that’s important. It was really comforting to hear how much they meant to everybody.”

How to Break the News that Someone Has Died

How to Break the News that Someone Has Died

”The Snow Sister” Directed by Cecilie Askeland Mosli

”The Snow Sister” Directed by Cecilie Askeland Mosli