Check out more of our Soulful Expressions posts here to explore more articles on art that inspire us to consider the way we approach death and dying.

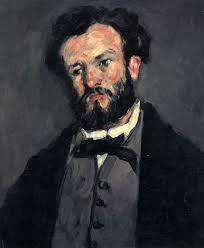

No one knows grief better than Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906). When I talk about knowing grief, I don’t mean in a moment of death or being in the presence of the dying — though those both played their part in his life. I want to speak about what it must have been like to live as an artist whose life and success was incessantly punctuated

by his own feelings of failure and loss. His painting “Sorrow” (1867), in which a male figure is depicted grieving, carries all the weight of Impressionism’s best underdog. Yet, as much as the piece is fraught with grief, there’s still something about it that’s steadying. There’s a softness amongst the pain – a settling into sorrow that doesn’t render the figure weak, but aware of his emotions.

His painting “Sorrow” (1867), in which a male figure is depicted grieving, carries all the weight of such a life.

Paul Cézanne was undoubtedly one of the late bloomers to success amongst his Impressionist and Post-Impressionist peers. He was the country bumpkin from Provence, France, who wanted to change our idea of what is real and perceived by capturing the most fleeting aspects of people and objects: the way light renders them uneven, imperfect and thus, otherworldly. He found beauty in the nuances of our surroundings and tried to capture them with his lush, famously spastic brushstrokes.

But not everyone loved his technique. He was endlessly rejected by the Salons in Paris and once called “a dirty little hedgehog of a man” by Manet. He never took hoards of lovers like Rodin, had low-self-esteem and despised socializing. His lifelong partnership to a woman named Hortense was tension-filled and tenuous, and he would confide in one of his only and closest friends, Émile Zola, on the anxiety he felt surrounded by others.

Today, Cézanne would have likely been diagnosed with depression and severe anxiety.

Today, Cézanne would have likely been diagnosed with depression and severe anxiety. At the time, his pain was chalked down to his merely being odd and unsociable. For anyone to have lived through such criticism and grief, both from others and himself, is a daily test of perserverance. Nevertheless, he never stopped painting. It was an instinctual gesture that caused him both frustration and happiness. Under such a light, Cézanne becomes an admirable man for those who are trying to do the same — and not just on the subject of painting.

“Sorrow” is a painting of contradictions: it’s dramatic, but uses a cool color palette; it contains classic elements (ex., the skull), but its technique is strictly “Cézanne.” The figure is exhausted by his grief, but wears an almost relieved look on his face that says, “I’ve embraced my grief. Now, it’s time to rest.” We can’t even distinguish what time of day it is in the soft, dappled lighting. It’s too ambiguous, but the important thing is that we know the brightness is there.

Cézanne: Letting the Grief Settle

Cézanne: Letting the Grief Settle

Octogenarian Author Jane Seskin Offers a Model for Aging and Living Well

Octogenarian Author Jane Seskin Offers a Model for Aging and Living Well

Are “Rage Rooms” a Healthy Outlet for Grief and Burnout?

Are “Rage Rooms” a Healthy Outlet for Grief and Burnout?