In devoting a week to India here at SevenPonds, we thought we’d take a look at Indian literature for this week’s “The Next Chapter.” The poem I’ve selected is “In Salutation to the Eternal Peace,” by Sarojini Naidu. Naidu is a fitting choice, since she herself joined Gandhi in the Salt March to Dandi, a part of the Indian Independence Movement. Her poetry is just as moving as her activism, and “Eternal Peace” is no exception.

In devoting a week to India here at SevenPonds, we thought we’d take a look at Indian literature for this week’s “The Next Chapter.” The poem I’ve selected is “In Salutation to the Eternal Peace,” by Sarojini Naidu. Naidu is a fitting choice, since she herself joined Gandhi in the Salt March to Dandi, a part of the Indian Independence Movement. Her poetry is just as moving as her activism, and “Eternal Peace” is no exception.

She begins by saying that people believe the world is a dark place, and that death is an ominous inevitability:

“Men say the world is full of fear and hate,/And all life’s ripening harvest-fields await/The restless sickle of relentless fate” (1-3).

In others’ eyes, all the beauty of the world, like “ripening harvest-fields” must come to a cruel and dreary end. Fate is “relentless” and “restless”; it affects everyone, and it never stops.

But Naidu doesn’t see the world this way. She states:

“But I, sweet Soul, rejoice that I was born,/When from the climbing terraces of corn/I watch the golden orioles of Thy morn” (4-6).

Naidu uses contrasts in her choice of words to show how differently she views things. Whereas the first stanza is full of negative, depressing words, the second is upbeat and positive, calling her soul “sweet,” and using imagery of sunrise, like “golden orioles,” or brightly-colored songbirds, and “morn.” This symbolizes her focus on the beginning of life, rather than the end. Instead of resenting the fact that she must die someday, she revels in the fact that she gets to live at all, “rejoic[ing]” that she was “born.” Even the image of “climbing terraces” depicts a kind of ascension, rather than being downcast.

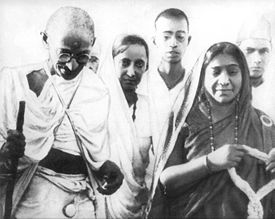

Naidu with Gandhi

At the end, the poet overtly mentions people’s fears about death, and rejects every one:

“Say, shall I heed dull presages of doom,/Or dread the rumoured loneliness and gloom,/The mute and mythic terror of the tomb?” (13-15).

The “doom” people speak of is just a boring and overused cliché, and the “loneliness and gloom” is only “rumoured”; therefore, Naidu does not believe it to be so. And finally, and most boldly, Naidu refers to the “terror” of death as simply “mythic”: it is fictitious.

In the poem’s final paragraph, Naidu proudly proclaims how happy she is with life, and her view of death:

“For my glad heart is drunk and drenched with Thee,/O inmost wind of living ecstasy!/O intimate essence of eternity!” (16-18).

Living, to Naidu, is “ecstasy,” and the fact that it is an “inmost wind” shows that it is a spirit within her that she holds onto. She is “drunk and drenched” with it, in her “glad heart,” because it fills her up completely, and makes her grateful to be alive. The “intimate essence of eternity” is her private knowledge that death is not scary, but something we should view merely as an extension of life. Eternity has the same great feeling as life does, in her view, and it is a view that we can all embrace.

“In Salutation to the Eternal Peace” by Sarojini Naidu

“In Salutation to the Eternal Peace” by Sarojini Naidu

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition