Bacteria under a microscope.

(Credit: fermup.com)

Since about the mid-19th century, people have been understandably afraid of germs. Prior to that time, no one knew why millions of people became mysteriously ill with symptoms such as fevers, rashes and coughs. Nor did they understand why so many of them died.

Then along came Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. Working separately, they came up with scientific evidence that illnesses such as cholera and tuberculosis were actually caused by microorganisms — bacteria, viruses, fungi and other tiny creatures known collectively as germs. Sanitation, pasteurization and antibiotics soon followed, and the era of fighting germs began.

Fast forward to the 21st century — the age of probiotics and superbugs. We have learned much about germs over the last 150 years, including two very significant facts. Antibiotics come with a price, and not all germs are bad. We now know that killing bacteria with antibiotics can encourage the growth of resistant bacteria that medicines can’t kill. What’s more, we know that many of the microorganisms that live in the human body play an integral role in the maintenance of optimal health.

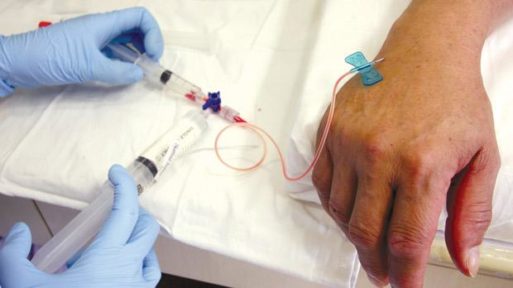

Now researchers at the Center for Infection and Immunity of Lille in France have made another fascinating discovery. Gut bacteria (germs that normally live in the intestine) can actually enhance the action of the anticancer drug cyclophosphamide. In a study reported in the journal Immunity, they found that two bacteria, Enterococcus hirae and Barnesiella intestinihominis, boosted the response of T-cells, white blood cells that fight infections and have an anticancer effect. The bacteria also enhanced the action of the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide and increased the efficacy of the drug.

Credit: timesofmalta.com

The researchers conducted the initial phase of the study on mouse models in the laboratory. In a second phase, they used human T-cells taken from patients with advanced ovarian cancer who had received chemotherapy. The results showed “T-cell responses specific to E. hirae and B. intestinihominis predicted progression-free survival.” In other words, T-cells exposed to either of the bacteria acted on cyclophosphamide in a way that could help patients live longer after treatment while preventing their cancer from getting worse.

The next phase of the research will be to identify how these two bacteria interact with cyclophosphamide. Specifically, the researchers will try to identify exactly what molecules are at work. According to study author and chief investigator Dr. Mathias Chamaillard, “Answering this question may provide a way to improve the survival of cyclophosphamide-treated cancer patients by supplementing them with bacterial-derived drugs instead of live microorganisms.”

Germs Help in the Fight Against Cancer

Germs Help in the Fight Against Cancer

“In Case You Don’t Live Forever” by Ben Platt

“In Case You Don’t Live Forever” by Ben Platt

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Our Monthly Tip: Make an “In Case of Death” File to Ease Loved One’s Grief

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival

Passing of Beloved Comedian Births a New Comedy Festival