Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) was the perfect target for both the dismissive, incensed judgment of art critics as well as the adoration of the larger public. His meticulous landscapes of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and Cushing, Maine captured the pristine, rural nature of the East Coast with great commercial success. At the age of twenty, he was, much like Rockwell, on his way to becoming the poster-child of Americana. Yet, many art critics wrote him off as a tired sentimentalist who put too much stock in cliché depictions of sprawling hayfields. Everyone else in the mid-century was gearing up for the abstract movement.

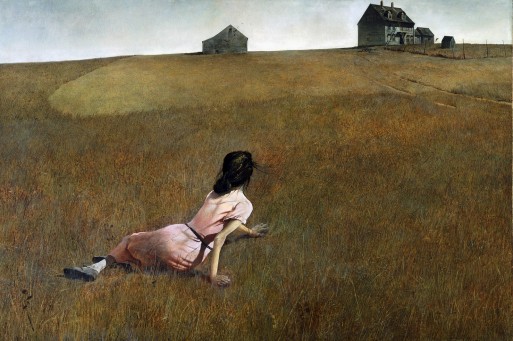

There is something inherently sentimental about Wyeth’s work. But what that sentimentality is intended to represent has been misunderstood by both those who loved and hated him for such rose-tinted patriotism. “Christina’s World” (1948), for example, is inextricably bound to a sense of American identity. But when you scrape the icing off the cake, in the case of “Christina’s World” and others, you’re left with much more universal themes of grief and loss.

The woman in the foreground of “Christina’s World” was actually Wyeth’s neighbor, who could barely walk due to polio. The entire scene is made somber by her position in it: her body twists languidly, but uncomfortably. We’ve no way of seeing her expression. We only know that she’s far from the only other sign of vitality: a rather austere looking country house.

If one were to describe the painting as, “a still field with a farm house, with a girl in a light pink dress reclining in the distance,” the whole thing would seem peachy. Kitsch. But it’s Wyeth’s use of sepia tones that casts an unsettling mood. His use of egg tempera creates what I can only call the fuzzy-sweater effect: a painting of warm but subdued subjects. We feel the coming of fall or the end of a dry summer. Either way, we can’t miss the sense that some heartbreaking displacement or transition is quietly taking place.

Andrew Wyeth with his son Nicholas and granddaughter Victoria at home in Maine in 1998.

(credit: boston.com)“I get letters from people about my work. The thing that pleases me most is that my work touches their feelings. In fact, they don’t talk about the paintings. They end up telling me the story of their life or how their father died.”

—Andrew Wyeth

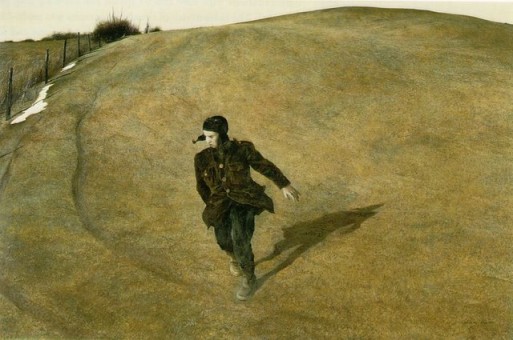

The most literal expression of grief in Wyeth’s work is his 1946 painting “Winter,” which depicts a lone boy running by the road of a barren hillside – the same road where Wyeth’s father died in a car crash. There’s a simultaneous sense of movement and paralyzation in the boy’s movement – exactly the sensation we feel when a loved one dies. The landscape shares the same color palette, the same grief, as its inhabitant. “I prefer winter and fall,” said Wyeth, “[it’s] when you feel the bone structure of the landscape—the loneliness of it, the dead feeling of winter. Something waits beneath it. The whole story doesn’t show.”

That’s why Wyeth’s work can’t be reduced to quaint dabbles in realist landscapes. There’s something profound beneath every brushstroke. We can’t see the whole story – but we can feel it.

You may enjoy:

- Cézanne: Letting the Grief Settle

- SFMOMA and Pauletta Chanco’s “Living on Shifting Sands”

- The Lifespan of a Poem: “And Death Shall Have No Dominion”

The Grief Beneath: Reflections Andrew Wyeth

The Grief Beneath: Reflections Andrew Wyeth

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?