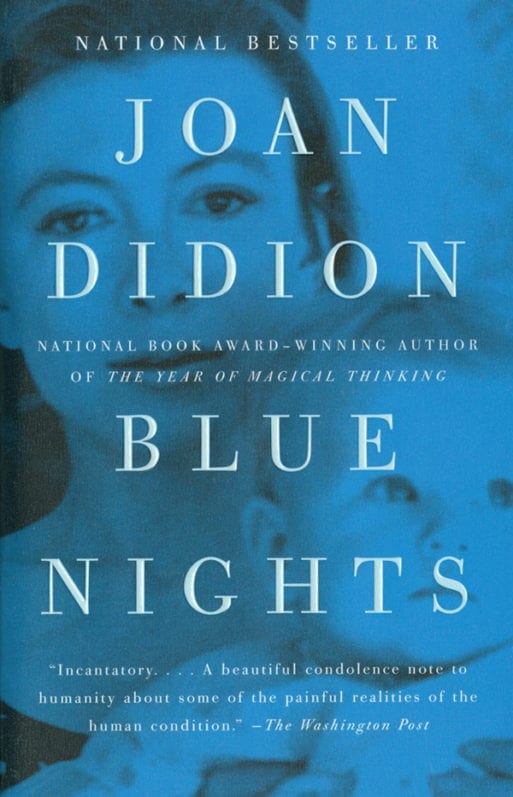

As husbands and wives age together, it is inevitable that one spouse will outlive the other. Burying one’s child, however, defies the natural order of generations and seems that much more insurmountable a loss. In 2005, the iconic American journalist Joan Didion poured her heart and mind into “The Year of Magical Thinking,” a now-classic memoir of mourning that reveals her earliest stages of grief after her husband John’s sudden death from a heart attack a year earlier. Before 2005 was over, the recently widowed Didion had to face yet another great loss: the death of their 39-year old adopted daughter Quintana Roo, a crushing blow. Didion writes about her grief in her second memoir of loss — “Blue Nights” –– published six years later.

Before writing both memoirs, Didion, now 84, had been revered for her informed and measured voice and was best known for her essays on the California subculture of the ’60s and ’70s. In 1991, she wrote the earliest mainstream media article — for The New York Review — that suggested the Central Park Five had been wrongfully convicted.

Didion applies the same journalistic inquiry and unrelenting honesty to her personal losses in both “The Year of Magical Thinking” and “Blue Nights,” though in “Blue Nights” she seems to delve more into emotional truths than indisputable details. In fact, even after one reads “Blue Nights,” the extended illness from which Quintana died is still somewhat unclear.

The only child of Joan Didion and John Dunne, Quintana had married just over a year before her death, in apparent good health. Her father died five months after the wedding. At the time of his death, Quintana lay in the intensive care unit at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City, suffering from a viral infection that had turned into pneumonia. She recovered, but a short time later she fell ill for nine months. After numerous hospitalizations for various conditions, she died. The reader is only told that complications ensued.

If one Googles the question, “What was Quintana Roo Dunne Michael’s cause of death?” a two-word answer pops up: acute pancreatitis. But those two words never appear in Didion’s “Blue Lights.”

Perhaps the whole experience was truly a blur for Didion. After all, she had just buried her husband and was experiencing her “year of magical thinking” — that most confusing and emotionally volatile start of long-term grief so familiar to those of us who have suffered great loss. Some suggest that Didion avoided– or may have been in denial — about the root cause of her daughter’s death since acute pancreatitis is often associated with alcoholism.

Didion seems to speak to the issue of veracity in “Blue Nights” when she writes:

“I tell you this true story just to prove that I can. That my frailty has not yet reached a point at which I can no longer tell a true story.”

Still, both physical and emotional frailty may have been an issue while writing memoir number two. All her life, acquaintances remarked about her tiny and thin body frame. A writer for the Guardian who interviewed her four months after Quintana’s death described Didion as “so slight as to be almost translucent.” According to a 2017 Netflix documentary on the writer, Didion dropped to just 75 pounds as she grieved.

The greatest truth in “Blue Nights” comes in the less verifiable category of emotional truth. The memoir’s structure seems to take on the uninvited questions that pop up willy nilly and often plague survivors after losing a loved one. In Didion’s case, these are questions about her role as Quintana’s mother — Did she raise her right, nurture her enough, protect her? Most of all, Didion grapples with how well she assuaged her daughter’s fear of abandonment — an innate worry many adopted children share.

As with all memoirs, much of “Blue Nights” is composed of memory. As readers are compelled to contemplate the aftermath of the unimaginable loss of a daughter so soon after the family patriarch’s death, they become, simultaneously, observers of that dear daughter’s wedding day. They are given a glimpse of how a precocious youngster rubs elbows with Mom and Dad’s celebrity friends on book tours and Hollywood sets. They are at her hospital bedside when she cannot quite comprehend her own father’s passing.

And even as Didion reminds us that “Time passes. Memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember,” the reader trusts her recollections. The memories are as random as the fates of those who are granted short or long lives. They are as meaningful as a page out of the Book of Wisdom if we allow them to be.

Instead of attempting to answer questions we may have about loss and grieving, “Blue Nights” raises more questions — deeper questions — about the survivor of a loss. Even as time and loss have worn her down, Didion manages to put forth more profound inquiries about grief.

“Blue Nights” by Joan Didion

“Blue Nights” by Joan Didion

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”