Ancient Greeks believed that at the moment of death, the psyche, or human spirit, left the body with the final exhalation. With this last little breath, the soul separated from the body, but lived on, unencumbered by its mortal form. In Plato’s Phaedo, Socrates, on the day before his execution by drinking hemlock, holds forth on the subject of the afterlife. He argues that the psyche is immortal, that the soul not only exists after death, but it continues to think. He states that the soul remains capable of attaining wisdom, and in fact is likelier to do so when it’s no longer bound by the body.

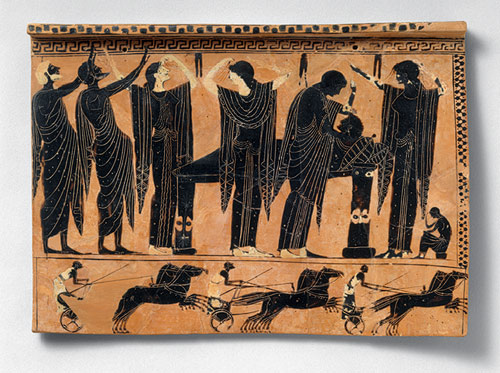

The Ancient Greeks practiced three stages of mourning: prothesis, ekphora, and internment or cremation. The requisite intricate burial rituals were primarily the responsibility of the female relatives and/or subjects of the departed. During prothesis, or the laying out of the body, female relatives washed and anointed the body with oil, then dressed it in an ankle-length robe, or a bridal gown if the person who had passed on was a recently-married woman, or battle armor if the person had been a soldier. The body was then laid out on a bed or sofa in the house, where mourners could come to pay their respects. Branches were hung over the body, and customarily a bowl of water was placed outside. Professional mourners would lead the singing or reciting of laments called threnos.

Just before dawn, the ekphora, a funeral procession would take place, during which the body was taken to the cemetery, which would have been located at the edge of town. The procession, at least in the time of Euripides, was a status symbol; the size of the procession, the size of the band of musicians, the number of professional mourners, and the quality and number of offerings all demonstrated the societal standing of the person who died.

Finally, the body was either cremated or buried. When inhumation took place, the body was not customarily buried with many objects, although the graves were frequently marked with giant earth mounds, monumental rectangular tombs or opulent marble statues. The more common practice, at least since the Homeric era, was cremation; remains were often placed in pottery urns.

After the Psyche Escapes

After the Psyche Escapes

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“The Sea” by John Banville

“The Sea” by John Banville