The Japanese mindset regarding suicide differs greatly from the outlook held by much of the rest of the world. The predominant belief in Japan holds that suicide can actually be a means of taking responsibility for an adverse life situation — a sharp contrast to the perception of suicide in many other cultures. The suicide rate in Japan is among the highest in the world, far outstripping the United States. The issue has become so extreme that Japanese citizens have begun addressing the situation in their own ways. One Japanese Buddhist monk has dedicated his life to assisting the problems of depression and suicide in his country.

Until recently, depression was not necessarily acknowledged in Japanese society as a legitimate health concern. As is true in many cultures, mental health afflictions carry a societal stigma; sufferers are thus urged to “keep it to themselves” when they feel unwell.

An extreme expression of this phenomenon is found in the hikikomori lifestyle, which has proven to be a psychological issue of its own. The hikikomori are people who live in acute isolation for at least six months and often much longer. Often, those who live a withdrawn life are at risk of suffering from depression, which can be both a precursor to and a symptom of the lifestyle.

In a Vice documentary, a Japanese suicide prevention patrol worker expresses his concern about the much broader social concern of isolation; he worries about the decreased human contact in our present society, saying, “I think the way we live in society these days has become more complicated.

Face-to-face communication used to be vital, but now we can live our lives online all day. However, the truth of the matter is [that] we still need to see each others’ faces, read their expressions [and] hear their voices.” That way, he says, “we can fully understand their emotions [and] coexist.”

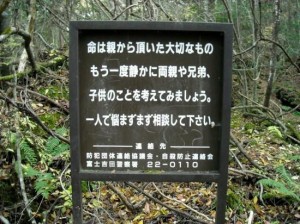

Aokigahara,a lush and dense Japanese forest that is the world’s second leading location for suicides (preceeded only by the Golden Gate Bridge), was described in The Complete Manual of Suicide as the perfect place to die. Signs are posted throughout the woods, urging suicidal visitors to reconsider their plans.

A patrol worker gives voice to the tragedy of the situation. “I think it’s impossible to die heroically by committing suicide,” he says, “You think you die alone, but that’s not true. Nobody is alone in this world. We have to coexist and take care of each other. ”

Related Links:

Aokigahara and Suicide in Japan

Aokigahara and Suicide in Japan

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?