Credit: Sikhism.ru

It’s not uncommon to find strict cultural rules that tell women exactly how to behave after a husband’s death. In some societies, women are expected to wear all black, cover the mirrors in their homes or even stay indoors for the duration of the mourning process. In societies that view marriage as the ultimate accomplishment for women, the death of a husband is considered the greatest loss in a woman’s life. As a result, these societies shun any woman who ignores mourning traditions.

Yet as strict as these traditions seem, all of these practices pale in comparison to the ancient Indian tradition of Sati, in which women would sacrifice their lives after their husbands’ deaths.

What is Sati?

Sati is an ancient Indian tradition that has been outlawed for many years. It was most common among  north Indian warrior tribes, and only a handful of communities practiced Sati regularly. After a husband’s death, a wife living in this kind of community was expected to throw herself onto her husband’s funeral pyre, effectively committing ceremonial suicide.

north Indian warrior tribes, and only a handful of communities practiced Sati regularly. After a husband’s death, a wife living in this kind of community was expected to throw herself onto her husband’s funeral pyre, effectively committing ceremonial suicide.

In many cases, women were either coerced into this practice through societal pressure, or physically forced into the act. With this in mind, it’s not entirely accurate to call Sati “ceremonial suicide,” as women were frequently not given a choice.

Nonetheless, many women willingly participated in this tradition until it was officially banned by the Indian government in 1829. To understand why this was the case, it’s important to consider the history of Sati and why it held such significance among warrior communities.

Sati’s History

Credit: wikipedia.org

Sati is actually a religious figure in Hindu texts. According to Hindu stories, Sati was a woman who adored and prayed to the god Shiva every day. One day, Shiva appeared and asked Sati to marry him. However, Sati’s father, who was notoriously cruel to her, disapproved of the marriage and openly insulted Shiva. As a protest against her father’s actions, Sati stepped into a fire, asking the gods to have her reborn as Shiva’s consort. In one of the earliest descriptions of reincarnation, Sati came back as Parvati, the goddess of fertility, love and devotion and Shiva’s wife, while her father came back as a goat.

But Sati’s death had nothing to do with the death of her husband, so why is her name associated with this tradition? It may be because this is one of the few Hindu stories that mentioned a pyre sacrifice from a devoted wife. However, many historians now believe that north Indian communities where Sati was common were directly influenced by the Scythians of Persia rather than Hindu texts.

The Scythians were an ancient nomadic people who would often bury their dead kings with their favorite servants, wives or concubines, believing that these individuals would continue to serve the king in the afterlife. In these cultures, women were considered the property of men, and their role in life (and in death) was to serve their husbands. Ritual Sati stemmed directly from these burial practices, but it was updated to account for India’s cremation practices. Rather than being buried with their husbands, wives would be burned with their husbands on the pyre.

Why Communities Practiced Sati

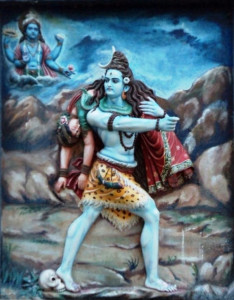

Shiva carrying Sati

(Credit: wikipedia.org)

Serving kings in the afterlife might have been the religious reason behind the practices of Sati, but many of these rituals served a more practical (and horrific) function in warrior societies. Since women could not own property or gain wealth on their own, they obtained it through marriage. Many powerful men believed that their future wives would only marry them for their wealth, and might murder them in order to get it. By requiring their wives to sacrifice themselves after their deaths, these men ensured that women married for love rather than wealth.

In warrior societies, community sacrifice was viewed as essential for everyone. Just as it was an honor for a man to die in battle, a woman was considered honorable if she participated in Sati. Those who refused the practice were often either forced into it or banished.

On the surface, this tradition was a way for women to express their grief for their husbands, but on a deeper level, it reflected the poor position women held in north Indian communities at the time. Women’s lives revolved around their husbands and their marriages, and when those were gone, life effectively ended for them.

Sati is a powerful example of how strongly culture, religion and war can impact our death rituals. While many of our modern death rituals are not nearly as extreme, they demonstrate that even modern societies are highly influenced by our communities and the opinions of our peers. Our traditions reflect what we value as a society and what we deem important when we grieve our loved ones.

Death at a Funeral: The Now-Extinct Indian Custom of Sati

Death at a Funeral: The Now-Extinct Indian Custom of Sati

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

Having an Estate Plan Is Essential – So Is Discussing It With Your Children

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales

“Summons” by Aurora Levins Morales