As people across the country cook and eat and drink, share laughter and arguments and stories for Thanksgiving, what this writer has always considered our most refreshing and simple national holiday, perhaps we might do well to remember the tradition’s less pleasant roots borne of the harsh reality of 17th Century colonial life, whose customs endured in spite, or perhaps because of such bitter trials. Death was an omnipresent reality to early North American settlers, and the first Thanksgiving was testament to those very challenges. Of the 102 Puritan settlers who disembarked from the Mayflower onto Plymouth Rock in 1620, only 56 survived the first year. It is believed that they would not have done so without the aid of Native American Indians, and, in the autumn of 1621 following a fortunately bountiful harvest, the surviving settlers sat down for a three-day feast with 91 members of the Wampanoag tribe, to offer their gratitude, their thanks. The feast was not repeated in the next year.

On into the 17th Century, death remained one of life’s constants. Disease, exposure, starvation, and war with native tribes all took their brutal toll. The Puritans maintained deeply held religious beliefs, and their practices in burial exemplify this, and, to an extent, continue to inform our own modern practices as well. That is, the use of a cemetery or small family plots, caskets and tombstones, though caskets in the 17th

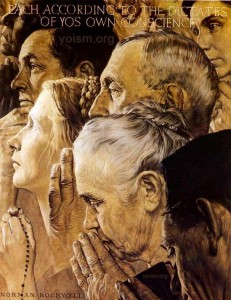

Century were typically simple oblong wooden boxes made of walnut, cherry, poplar or mahogany, and tombstones were plain slabs of stone, typically inscribed with the decedents name and dates of birth and passing, as well as a short epigraph. Early Puritans believed elaborate burials to be idolatrous. Death was a feared, yet necessarily embraced part of life, and especially following the Great Awakening in the 1720s, a period of intense religious revivalism that swept the New England colonies, death was placed in the context of a reunion with God, rather than a departure from the earth, where the soul might endure, and help to inform the living. While a “Day of Thanksgiving” was declared in Charleston, Massachusetts in June of 1676, to honor the good fortune the settlers had enjoyed in becoming a firmly established community, it was not until 1777 that all 13 colonies joined in national day of thanks, a national holiday, in part commemorating their victory over the British at Saratoga — a far cry from the first Mayflower settlers’ feast of gratitude with the native peoples who had helped them.

So, while we sit down to eat and drink among our family and friends, we might wish to raise a glass to those who have gone before us. Perhaps it is they as well that we should truly thank.

Life, Death and Burial in Colonial America

Life, Death and Burial in Colonial America

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

“Songbird” by Fleetwood Mac

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One