Every May, I find myself scrambling to finish final papers, study for exams, finish out the school year, and most importantly find something to give my mother. I’ll love my mother more than she’ll ever know, but every year around the second week of May, I end up presenting her with the same corny card or box of chocolates. While writing my senior thesis and dreading this year will end up the same, I thought, has it always been this way? As we approach Mother’s Day 2012, I figured we could take a look into the history that made the holiday what it is now.

I was surprised to find that unlike the long history of motherhood, their commemorative day isn’t all that old. A few women’s peace groups bumped around ideas in the late nineteenth century when our country was wrecked by war and overwhelmed with loss. Their efforts made an impact on a local level but never got national recognition. Ann Jarvis wholeheartedly endorsed a commemorative day for mothers in 1868, but the idea never took off by the time she reached her death in 1905.

“I was surprised to find that unlike the long history of motherhood, their commemorative day isn’t all that old.”

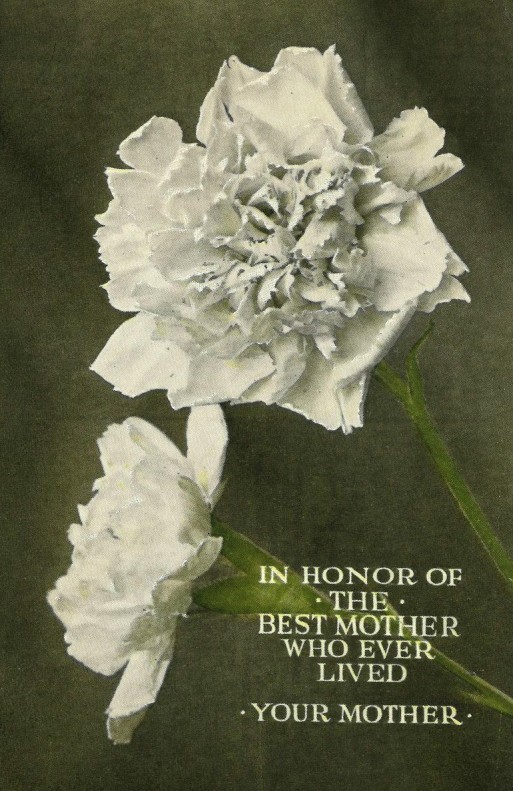

It would take Anna Marie Jarvis, Ann Jarvis’ daughter, to promote the holiday as we know it today. Shortly following her mother’s death, Jarvis made a promise to herself that she would establish a day to honor mothers. Initially, the day had more formal aspects that sought to commemorate mothers who had passed. In 1907, Jarvis passed out five hundred white carnations—her mother’s favorite flower—at her local church in West Virginia. After that small ceremony, a Mother’s Day campaign was formed.

“Shortly following her mother’s death, Jarvis made a promise to herself that she would establish a day to honor mothers.”

By 1908, the increasing popularity of Mother’s Day ceremonies prompted the Young Men’s Christian Association to present a bill to the U.S. Senate to make the holiday official. Although it didn’t pass, by 1909, forty-six states (as well as parts of Mexico and Canada) were celebrating Mother’s Day in some form. Soon after, Anna Jarvis quit her job in order to devote herself fully to the cause. In 1912, West Virginia became the first state to announce it would officially adopt the holiday, which prompted Woodrow Wilson to sign it into national observance in 1914. From then on, the second Sunday of May would be recognized as Mother’s Day.

While Anna Jarvis succeeded in making Mother’s Day a national holiday, she was not altogether pleased with the outcome. By 1920, it was already highly commercialized. This troubled Jarvis to the point that she disrupted several Mother’s Day events that sold flowers. As she said herself, “A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world. And candy! You take a box to Mother—and then eat most of it yourself. A pretty sentiment.”

“What started as a memorial for one mother morphed into a celebration of every mother.”

Anna Jarvis’ life story now exists as a series of ironies. She devoted her life to establishing Mother’s Day only to rail against it near the end of her life. She is considered the mother of Mother’s Day and yet she had no children herself. When she became blind and sickly in her old age, The Florist’s Exchange anonymously paid for her care.

What started as a memorial for one mother morphed into a celebration of every mother. Even though Jarvis didn’t fully obtain what she envisioned, the fact still stands that we have an organized day on which mothers are recognized, whether they are still in our lives or have passed. If we can learn anything from this brief history of Mother’s Day, perhaps it would be to continue the celebration into every day. I think Anna Jarvis would agree that it doesn’t take a card to tell our mothers we love them.

The Daughter Who Started It All

The Daughter Who Started It All

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”