Sora woman smoking

Credit: Dietmar Temps

Residing in the highlands of eastern India, a native tribe called the Sora hold a special relationship with their dead, bringing their loved ones to the forefront of everyday life.

Core Beliefs of the Sora

Should you visit a Sora village on any given day, you would find lively conversations happening all around you. And while a majority of these conversations would be happening among villagers, some are taking place between the living and the dead through the mouth of a shaman. For the Sora, talking with the dead is a part of everyday life.

For them, death is not an end, but rather another phase of existence that can still be reached by the living via a shaman. They believe that when a person dies, they become a “sonum.” While a Western reader might try to conceptualize a sonum as something akin to a spirit, there are key differences between the two that makes the word “spirit” a poor translation.

In the Western world, spirits are typically understood to be a shapeless essence coming from some spiritual realm. They exist without an identity, acting as guiding forces that communicate through ambiguous feelings rather than words. While sonums are understood by the Sora as being from another realm called the Underworld, they couldn’t be more conceptually different. Sonums retain the personalities of their earthly lives, and in their new life in the Underworld, they might remarry, work at a job or enjoy new friendships. Further, while sonums can go about influencing the living as spirits do, the Sora believe that they also have the capacity to influence the dead.

Piers Vitebsky, a British anthropologist who studied Sora culture in India during the 1970s, wrote much of what we know about the culture in his book, “Dialogues with the Dead: The Discussion of Mortality Among the Sora of Eastern India.” In his book, he emphasizes the reciprocal nature between the Sora and sonums.

“An illness in a living person is a reflection of a mood or attitude in a dead person, and the rite which heals a sick person is also a rite to acknowledge the claims of the ‘sonum’ who has attacked him,” Vitebsky wrote.

In other words, a sonum can bring illness upon a village member, but a shaman can block this from occurring with a certain rite or ritual. Sonums’ impact on the community is not solely adversarial. They can also foster fertility and positively influence agricultural cycles.

Funeral shaman in a trance

Credit: Scientific American

The Sora’s unique understanding of the dead make conversations with sonums a near daily occurrence.

Funeral Practices of the Sora

Sora funerals are unconventionally long, run over the course of three years, involving numerous rituals and dialogues facilitated by shamans.

Upon a death, the women of the house begin lamenting while a group of drummers and oboe players assemble to perform a “death beat,” notifying the village of the loss. Hearing the familiar beat, the men pause their activities to construct a pyre for the deceased.

Women strip the body, wash it in turmeric water, dress it in fresh attire, and place it on the pyre for cremation. The villagers then collect the ashes and placed them in a designated area of the village.

A funeral shaman, typically a woman, enters a trance and guides the sonum into the family’s dwelling, where the family engages in an initial dialogue with them. These dialogues primarily focus on the circumstances of the sonum’s death. Family members often adopt a confrontational stance, seeking consensus on the cause of death. The interrogation lasts until an agreement is achieved.

This discussion assumes precedence due to the belief that the sonum may attempt to inflict a similar fate upon the community. For instance, if an individual succumbed to leprosy, their sonum, if not properly addressed through blocking rites and rituals, will try to spread the disease among the living.

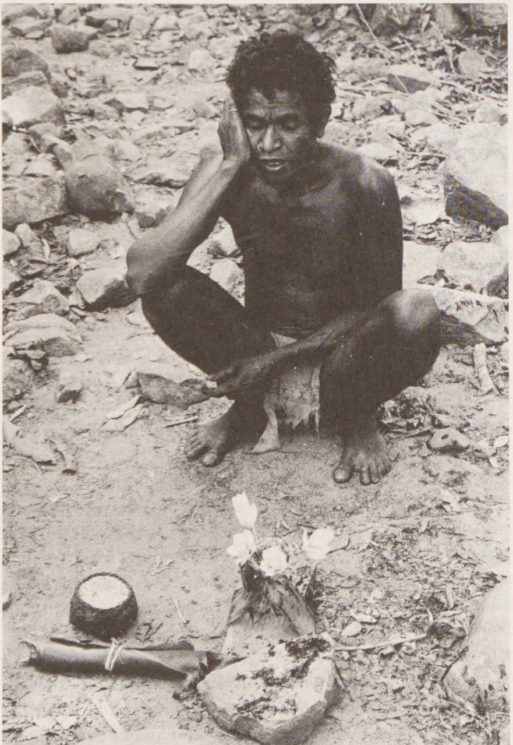

A divining and healing shaman banishing a sonum using frangipani flowers and banana leaves

Credit: Vitebsky, “Dialogues with the Dead”

A few weeks later, the family commemorates the dead by erecting an upright memorial stone, among other stones from previous funerals. This act symbolizes the commencement of the sonum’s long odyssey to confront their own death in the Underworld.

From this point forward, dialogues between the sonum and the village occur regularly. The living accompany the sonum throughout their odyssey, gaining insights into their thoughts, attitudes, and life in the Underworld. Sora villagers generally communicate throughout their lives with the same sonums who can one day act as a nurturing sonum, and on another day act as an antagonist to the community by spreading illness. The dead, therefore, are active members of the community and of daily life.

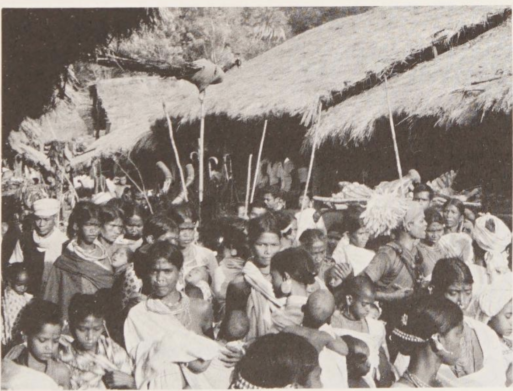

Sora funeral celebration

Credit: Vitebsky, “Dialogues with the Dead”

The funeral ritual concludes years later when the sonum’s name is bestowed upon a child during a naming ceremony, marking a joyous transition into the next generation.

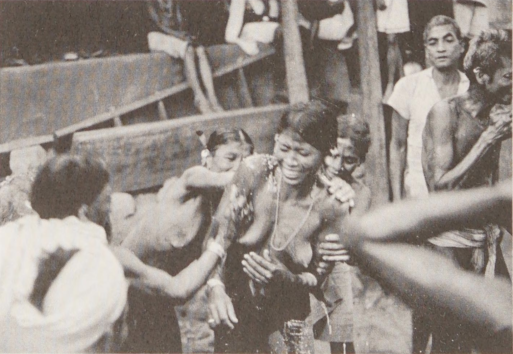

Tumeric fight at a toddlers’ name-giving ceremony

Credit: Vitebsky, “Dialogues with the Dead”

The Sora believe that after many years, the sonum experiences a second and final death, transforming into a butterfly. To the Sora, the butterfly is the perfect symbol to capture the final death of a sonum. Unlike sonums, butterflies lack individuality and the ability to communicate.

Vitebsky describes the transition well. “Incapable of activity and action, liberated from passivity and passion but also deprived forever of company, butterflies are Memories without rememberers. This, at last, is the final death of the person.”

Implications for Western Cultures

The Sora’s approach to death offers valuable lessons to Western readers. While Western culture often encourages mourners to swiftly “move on” after a death, the Sora engage intimately and earnestly with their loved ones through intricate rituals and conversations that resolve previous conflicts. The Sora tradition inherently honors the grieving process, fostering communal support and facilitating much needed closure at an unhurried pace.

“Dialogues with the dead are not about death, but about life: it is only by having a vision of what it is to be dead, that one can have an understanding of what it is to be alive,” Vitebesky concluded.

Unfortunately, since the 1970s, when much of this research on Sora traditions was conducted, the population has steadily declined, with many converting to Hinduism or Christianity. Vitebsky, the researcher who initially studied the Sora in the 1970s, returned after the COVID-19 pandemic to witness the change.

In a 2023 article for Scientific Magazine, he lamented, “Biology teaches us that diversity of forms in general enables adaptability and survival. The extinction of traditional Sora thought constitutes the loss of yet another species of theodiversity, a major resource for future-proofing a planet racked by contested histories, degraded environments, irresponsible governments and perpetual war.”

As the world continues to see a decline in Native traditions, the preservation of such traditions becomes not only a testament to the past but also a beacon of wisdom that can better inform our own relationship with death.

Dialogues with the Departed: Unveiling the Intricate Funerary Traditions of the Sora Tribe in Eastern India

Dialogues with the Departed: Unveiling the Intricate Funerary Traditions of the Sora Tribe in Eastern India

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Making Mobiles” by Karolina Merska

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

“Hands Up to the Sky” by Michael Franti & Spearhead

Coping With Election Grief

Coping With Election Grief