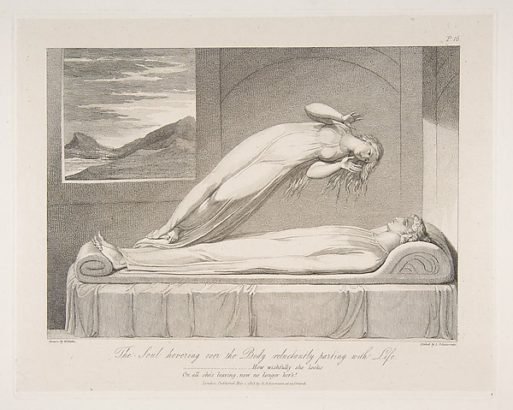

Despite the huge variation in cultural practices around death that exist across the globe, there is one area in which most cultures agree — the existence of the soul. Definitions of exactly what that is differ widely, yet most modern cultures share several core beliefs. These include the idea that the soul exists independently of the physical body; that it is the essence of our spiritual or divine selves; and that it is immortal. This spiritual immortality is also integral to the belief in an afterlife — a separate plane of existence in which the soul lives on, either in another dimension, a celestial realm or in reincarnated corporeal form, after the body has died.

Of course, no one has ever proven the existence of either the soul or an afterlife, despite the ubiquity and pervasiveness of these beliefs. Some researchers claim that near death experiences offer proof that a part of the self lives on after death, yet the claim is controversial at best. Even complex, well-designed scientific studies have failed to establish that consciousness exists after death, or that the experiences of those who have come close to dying are not simply the by-product of brain processes shutting down.

Of course, no one has ever proven the existence of either the soul or an afterlife, despite the ubiquity and pervasiveness of these beliefs. Some researchers claim that near death experiences offer proof that a part of the self lives on after death, yet the claim is controversial at best. Even complex, well-designed scientific studies have failed to establish that consciousness exists after death, or that the experiences of those who have come close to dying are not simply the by-product of brain processes shutting down.

The 21-Gram Experiment

Which brings us to an interesting experiment conducted by Dr. Duncan MacDougall of Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1901. MacDougall sought to establish not only the existence of the soul but to determine its weight. His ultimate purpose was to prove that the soul was a physical presence within the body, with substance and mass.

For the experiment, MacDougall chose six patients from a nursing home who were close to death. When he determined that death was imminent, he had the patient, still in his or her bed, placed on an industrial scale that was accurate to 0.2 ounces, or 5.6 grams. Once the bed and patient were in position, MacDougall weighed them and waited for the person to die. He then weighed the bed and the patient at the time of death (it’s unclear how the exact moment of death was determined) and several times thereafter. According to his published account, fluid losses from other sources, such as respiration and sweat, were carefully accounted for.

From a scientific standpoint, MacDougall’s experiment was a colossal failure. His results were remarkably inconsistent: one patient lost three quarters of an ounce (about 21 grams); one patient lost half an ounce (about 14 grams); one patient lost one-and-one-half ounces (about 43 grams); and one patient lost half an ounce, then another ounce several minutes later for a total of an ounce and a half. The fourth patient lost three-eighths of an ounce (10.5 grams), gained it back again, and then lost it again after 15 minutes. The results of the fifth and sixth tests were discarded for technical reasons, MacDougall later wrote.

Duncan MacDougall

Despite these inconsistencies and the difficulty in determining the exact moment of death, MacDougall drew the conclusion that the weight of the soul was between three quarters to one and one half ounces, or 21 to 43 grams. He did, however, admit that further experiments would be needed to validate his results.

MacDougall then went on to repeat the same experiment on 15 dogs, who demonstrated no weight loss upon their demise. MacDougall used this result to bolster his theory about the weight of the soul since, according to his belief system, humans have souls and animals do not. (Of interest is the fact that MacDougall was unable to find 15 dying dogs for this part of the experiment, so he most likely killed the dogs intentionally. As author Mary Roach wrote at the time, “barring a local outbreak of distemper, one is forced to conjecture that the good doctor calmly poisoned fifteen healthy canines for his little exercise in biological theology.”)

MacDougall’s experiments were widely discredited when he published his results in 1907, six years after the fact. The small sample size, the inconsistent weight loss and the fact that his ability to precisely measure such minuscule numbers prompted most in the scientific community to dismiss the results as either wishful thinking or out and out fraud.

And yet, amazingly, MacDougall’s wildly improbable theory that the human soul weighs between 21 and 43 grams (distilled in popular mythology to 21 grams) persists in the minds of many a believer today. Google the question “What does the soul weigh?” and you will be served up millions of results, many of which lend credence to MacDougall’s theory. A popular 2003 crime drama, “21 Grams,” even borrowed its title from the mythical 21-gram soul.

Why the Myth Persists

Belief in a divine presence, a soul and/or an afterlife is strictly a matter of faith. Although these beliefs are shared in some form by a large percentage of the human race, they are, by their very nature, unprovable and improbable on their face. No one can know what happens to use after we die. And that mystery is one of the greatest sources of humankind’s collective fear of death. We want to know what will happen to us. We want certainty in our lives. More importantly, we want to believe that death is not the end — that some part of us will live on when our bodies are no longer alive.

Of course, certainty is an illusion, the only thing we know for certain is what is happening in the here and now. But what better better way to feel assured of eternal life than to perpetuate the myth that, once upon a time, a doctor was able to demonstrate that the immortal soul exists?

The Weight of the Soul

The Weight of the Soul

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

National Donate Life Month Reminds Us To Give

How Dare You Die Now!

How Dare You Die Now!

Debating Medical Aid in Dying

Debating Medical Aid in Dying