Life was brutal for many Indonesians in the mid-1960s, unless you happened to be a gangster selling movie tickets on the black market.

They also extorted money from Chinese people living in the area. When they could not pay, they were killed.

This is how Anwar Congo got his start as one of the most feared men in his town. When tensions mounted between the government and communist rebel fighters in the early 1960s, government officials hired prominent gangsters to carry out nationwide executions of people suspected to be communists. They also extorted money from Chinese people living in the area. When they could not pay, they were killed.

About 500,000 people lost their lives that year.

If you expect this story to have a happy ending, it doesn’t. Today, Anwar and his colleagues are revered members of their community. Young people in the paramilitary group Pemuda Pancasila look up to Anwar as a leader and an example of a high-quality man. This is one of the perks of winning a war.

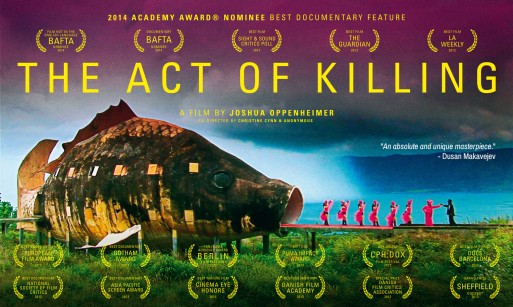

It’s still a dangerous time to be accused as a traitor in Indonesia, so when Joshua Oppenheimer set out to make his documentary The Act of Killing, he had trouble forming a story around the survivors. The group of survivors told him to talk to the killers instead.

The Act of Killing cuts between scenes from Anwar’s “movie” and scenes of Anwar making decisions about what to wear, where to film and how his actors should say their lines.

The resulting documentary is unlike anything else in the genre. Oppenheimer tells Anwar to direct his own dramatized account of what his life was like when he killed people in the 1960s. The Act of Killing cuts between scenes from Anwar’s “movie” and scenes of Anwar making decisions about what to wear, where to film and how his actors should say their lines.

In early scenes, Anwar dances around an outdoor patio where he remembers killing hundreds of people between 1965 and 1966. He laughs with his colleague and boisterously tells stories about how he would hit on women outside of the movie theater across the street before coming upstairs to strangle someone on the patio with wire.

He says over and over that “gangster” means “free man,” and he’s proud to be a gangster.

At his most confident, Anwar views himself as John Wayne or Marlon Brando. He says over and over that “gangster” means “free man,” and he’s proud to be a gangster. You hear Indonesian government officials use the same rhetoric in their speeches.

Anwar and many of his peers say they believe that what they were doing in the 1960s was fighting for freedom. As movie fans, his colleagues took their cues from American actors. They worshiped the stoicism of John Wayne and the brutality of New York gangsters in films. These were free men doing as they pleased and taking disrespect from no one.

Warning: The next paragraph contains major spoilers for The Act of Killing.

The illusion Anwar has for himself comes into full bloom toward the final scene of his “movie.” He stands in front of a waterfall on a cluster of rocks, surrounded by glowing, singing women. It’s his version of what heaven looks like. On his right, two men take off the wire around their necks. One of the men places a medal around Anwar’s neck and says, “Thank you for freeing us by executing us and sending us to heaven.”

But for all of the shallow Western films Anwar claims to align his life with, and for all of the talk about freeing people from their earthly prisons, by the end of the documentary, Anwar seems to fully grasp what he did for the first time.

He tells Oppenheimer that pretending to be executed in his movie made him feel afraid. He said he could feel what his victims must have felt. Oppenheimer corrects him. His victims didn’t feel the same fear as Anwar, because their fear was real. Their deaths were real.

When Anwar returns to his patio where he killed so many people decades ago, he dry heaves. Where he once proudly demonstrated the cleanest way to kill a human being, he picked up his wire and doubled over in a cough. Once proud and self-assured, in the end, he says he isn’t sure whether what he did was a sin.

Nationalism and pride form a protective bubble around those who kill, one that can only be broken through seeing what they did objectively.

Remorse is a cross-cultural emotion, but Anwar’s story is an example of how fluid this emotion can be. What happens when you’re not only unpunished for murdering hundreds of people, but you are actually viewed as a hero? Remorse has no place in this situation. People are hard-pressed to feel sorry for something no one else around them sees as wrong. Nationalism and pride form a protective bubble around those who kill, one that can only be broken through seeing what they did objectively.

The Act of Killing proves that no matter where you were born, guilt and mourning only apply if you lose the war.

What Does Genocide Look Like Through the Eyes of a Killer?

What Does Genocide Look Like Through the Eyes of a Killer?

“Help Me, Helen”

“Help Me, Helen”

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

Recovering Cremation Remains After the Los Angeles Fires

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull

“As Tears Go By” by Marianne Faithfull