A watcher determined if a person had died

Throughout most of modern history, caring for the sick has been “woman’s work.” Doctors — almost exclusively men — formulated diagnoses, dictated orders and performed surgeries. But the hands-on care of the ill and infirm was almost always a woman’s job. Even before French nurse, Jeanne Mance established North America’s first hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, in 1645, women would nurse the poor in their homes.

And so it should come as no surprise that, in the days before undertakers became the caretakers of the dead, caring for the dying and the bodies of those who had recently died was woman’s work too.

“The Watchers”

In early 19th-century America (and possibly long before that) women were tasked with caring not just for the sick, but for the actively dying. According to historian Karol K. Weaver, these “watchers” or “watch-women,” stayed at the bedside when death was anticipated, administering physical care and reciting prayers. They also contacted clergy and family members and reported to them about the dying person’s attitude as death approached. If the person was stoic and courageous, their demise was reported as a “Good Death,” which comforted the family and gave them hope for their loved one’s everlasting soul. If, on the other hand, the death was painful and difficult, it was reported as a “Bad Death.” This was generally taken as a sign that the person had been insufficiently penitent at the end of their lives.

Credit: jstordaily.org

Most of the watchers were family members or friends, but sometimes professional watchers were hired to perform the job.

Another (and arguably the most important) role of a watcher was to verify that a person had actually died. They would watch for the cessation of breathing and shake the person to see if they could be aroused. After a sufficient amount of time had passed, they would announce to the family that the person had died.

The Layers Out of the Dead

Once a person was determined to be dead, the role of the watchers ended, and the “layers out of the dead” stepped in. Also women and often family members, these caretakers of the dead would wash and dress the body and put coins or some other object over the eyes to keep them closed. In many cases, a stick would be placed on the chest and propped under the chin to close the mouth.

While many layers out of the dead were family or friends, a number of them were professionals who were trained to perform some of the activities that undertakers do today. They might, for example, remove internal organs to slow putrefaction or plug the body’s orifices to prevent fluid from leaking out. In some instances, they would fill the emptied body cavities with charcoal, or apply an alum-soaked cloth to the body, which also served to slow decomposition down. (Home refrigerators weren’t widely available until the early part of the 20th century, so there was no possibility of keeping the body cool.)

Interestingly, according to Weaver’s research (which focused on early 19th century Philadelphia), many professional layers out of the dead advertised their services in local business directories, often calling themselves nurses and/or midwives. Some also identified themselves as widows, which Weaver surmises was a way to explain their need to work for money, which was frowned upon at the time. In fact, according to research conducted by Randall H. Hall, professional nurses who cared for the sick were often vilified for stepping outside their “proper” role. This was especially true in the South.

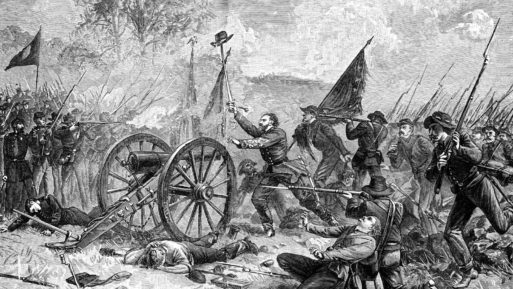

The American Civil War led to the rise of male undertakers

Credit: myjewishlearning.com

The Rise of Undertakers

Then, around the mid-19th century, caring for the dead slowly morphed from a role filled by women to one assumed primarily by men. Nursing the sick was still largely woman’s work. But, as the Civil War raged on and the need to transport dead bodies long distances became more and more acute, professional undertakers took over the role. Usually father-son teams, they not only prepared bodies for burial but also built coffins and provided hearses to carry the dead to their final resting place.

By 1867, there was just one female undertaker and four layers out of the dead listed in Philadelphia. There were 125 male undertakers, a definite indication that death was woman’s work no more.

When Death Was “Woman’s Work”

When Death Was “Woman’s Work”

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition