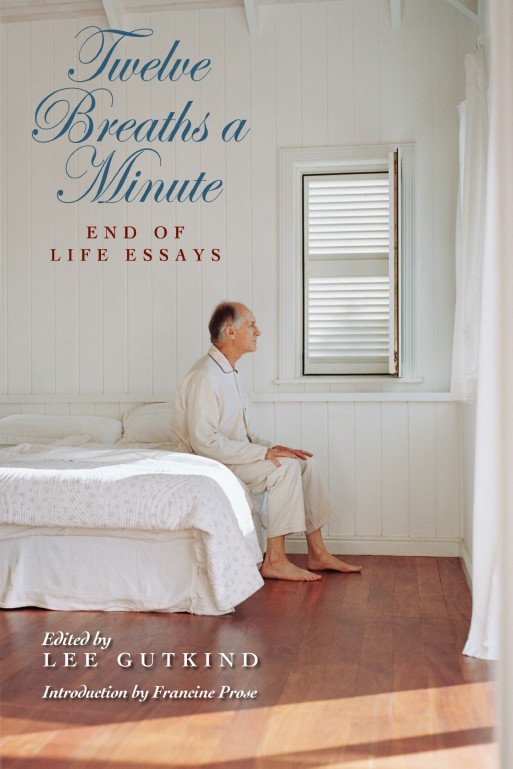

Much like our Opening Our Hearts series here on the SevenPonds blog, Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays is a book filled with essays about people’s personal experiences with the end of life. As the editor Lee Gutkind notes, Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays is a project of the Creative Nonfiction literary magazine and it is “part of a series of narrative books on science and medicine supported by the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.” While the book’s mission is to extend the conversation on the topics of death and dying among all kinds of people in the community, I struggled to find the accuracy in their intended goal when it seemed like more of the essays selected for publication came from medical providers than from laypeople.

There were times, however, when some of the essays would drag on and I would lose interest in the book and would leave it sitting on my bedside table.

Don’t get me wrong; some of the essays in Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays were filled with beautiful words and inspiring messages. Clearly, some of the people, including the medical providers, who submitted essays are truly gifted storytellers in their accounts of their personal experiences of going face-to-face with their end-of-life experience. There were times, however, when some of the essays would drag on and I would lose interest in the book and would leave it sitting on my bedside table.

“…Death is greeted with the bitterness of regret only if it brings the realization that our time has had no meaning.”

One of the shining examples of an essay that beautifully blended imparting useful knowledge and sharing personal examples of encounters with people facing the ends of their lives would be medical resident Amanda J. Redig’s “The Measure of Time.” She blends some discussion of the etymology of two Greek words, “chronos” and “kairos,” and how they relate to time when it comes to those facing death and dying along with her personal anecdotes of patients she lost. “Chronos” is the literal meaning of the word, “time;” whereas “kairos” means the “right time, the time when something of great importance occurs.” When discussing “the adversarial relationship with death” that physicians are known to have, I found it fascinating that she muses about how doctors’

“lab coats are white, as if the ability to bleach away the stains bestows the added power to make bad things to go away with the wave of a stethoscope. In truth, black would be a more appropriate color…But no one goes to a physician to be reminded of a funeral…” She concludes her essay with a beautiful reminder that “death is the end of time on this earth, but even when the coming of those last days is upon us, life can still be full of purpose, even when that purpose carries a taste of the bittersweet. This truth is easily lost amid the machines and technology of medical achievement. The greatest gift we can give our patients and their families is not chronos but kairos, the opportunity to transform empty moments into those of profound value…Death is greeted with the bitterness of regret only if it brings the realization that our time has had no meaning.”

Overall, the book left me feeling very depressed and angry about how the topic of death and dying is still being treated in the majority of the medical community in the United States.

Overall, the book left me feeling very depressed and angry about how the topic of death and dying is still being treated in the majority of the medical community in the United States. While many are trying to change the focus away from the long-ingrained plight of commercialism in funerals and striving to perform heroics to avoid losing patients to death for as long as possible, the examples mentioned in the essays in Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays demonstrate that much more work and advocacy needs to be done among those passionate about the topic in order to ensure good deaths for future generations.

Check out more of our library of book and film reviews here.

Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays/Edited by Lee Gutkind

Twelve Breaths a Minute: End-of-Life Essays/Edited by Lee Gutkind

The Other Death in the Family

The Other Death in the Family

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls

The Healing Sound of Singing Bowls