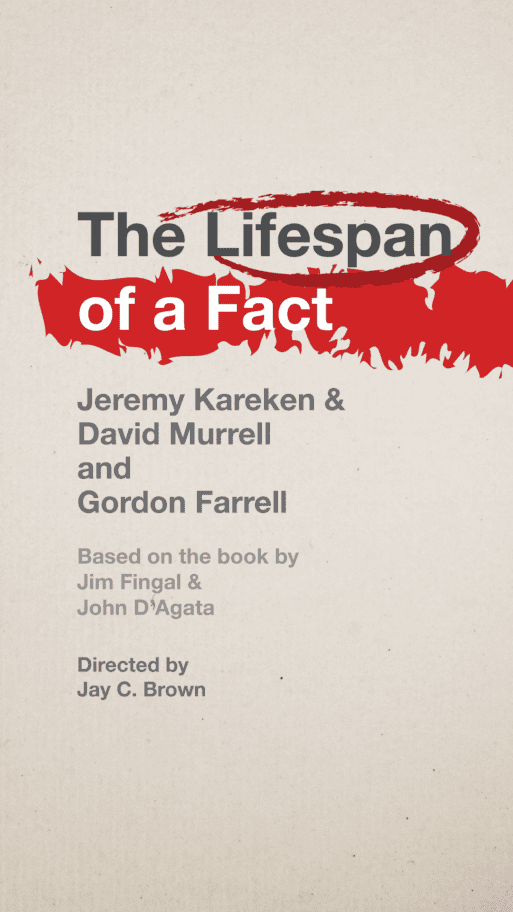

As some might remember, there was a bit of an uproar this past winter over a thin, somewhat funny-looking book called The Lifespan of a Fact by John D’Agata and Jim Fingal. Although it did receive much attention, it’s hard to say whether it was a hit or miss considering the wild range of reviews—some were enamored while others were appalled. I suppose the first problem we face as reviewers would be summing up the work, which is not an easy task. At its core, Lifespan follows the email correspondence between an author (D’Agata) and the fact-checker (Fingal) who is trying to sort through the factual discrepancies of his essay about a boy’s suicide in Las Vegas. But even that description could be a bit tricky if you’ve read the book. The big question comes down to: why would a book about fact checking elicit such a heated response?

As some might remember, there was a bit of an uproar this past winter over a thin, somewhat funny-looking book called The Lifespan of a Fact by John D’Agata and Jim Fingal. Although it did receive much attention, it’s hard to say whether it was a hit or miss considering the wild range of reviews—some were enamored while others were appalled. I suppose the first problem we face as reviewers would be summing up the work, which is not an easy task. At its core, Lifespan follows the email correspondence between an author (D’Agata) and the fact-checker (Fingal) who is trying to sort through the factual discrepancies of his essay about a boy’s suicide in Las Vegas. But even that description could be a bit tricky if you’ve read the book. The big question comes down to: why would a book about fact checking elicit such a heated response?

When we look at the reviews, it seems like everything is fair game to pick over. Some critics took a look at specific writing devices, while others attacked the character of the writers themselves. For example, Jennifer McDonald wrote in her review of the book for The New York Times, “It’s telling that in the heat of battle D’Agata resorts to playground taunts… D’Agata’s attachment to his precious words might be less exasperating were his defenses not so frequently flimsy.” She does make some good observations about D’Agata’s righteous persona in Lifespan, but those observations are not helpful to our understanding of the subject matter or particularly relevant. Ironically, the publishers provide a blurb from her review that is twisted enough to applaud the book.

A review from NPR is unsurprisingly more objective and comprehensive. In it, Alice Gregory writes that the work “points up the near-impossibility of imposing moral responsibility on a genre as ill-defined as nonfiction.” It is true that, through the course of the book, there are many ethical debates that erupt between John and Jim. Jim tries to nail down the precise details of every event while John solidly stands by his artistic reasoning for the way writing and research should be done. As Jenny Hendrix writes for The New Republic, “The book trails on long after the conclusion of D’Agata’s essay as Fingal attempts, painstakingly, to reconstruct the sequence of its dramatic finale, searching for the place where either D’Agata or his sources erred in their timing of Levi’s death. It’s a heartrending effort… Something’s awry, Fingal senses, and yet: ‘I don’t know.’ In the end, the ‘why’ remains elusive, even when the facts are sound.”

“A review from NPR is unsurprisingly more objective and comprehensive.”

On the one hand, there is the real-life loss of a young boy that demands respect. On the other, there is the idea of telling true stories as a form of art. Both of these objectives clash when viewed from a moral standpoint because no one wants to feel manipulated when talking about death. If this book were about the fact checking of cooking recipes or the history of steel pipes instead of death, I don’t think there would be the same gravity.

“The Lifespan of a Fact” by John D’Agata and Jim Fingal

“The Lifespan of a Fact” by John D’Agata and Jim Fingal

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

First the Wealth Gap, Now the U.S. Has a Growing Health Gap

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

How to Comfort A Dying Loved One

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition

Our Annual Seven Holiday Gifts for Someone Who Is Grieving, 2024 Edition